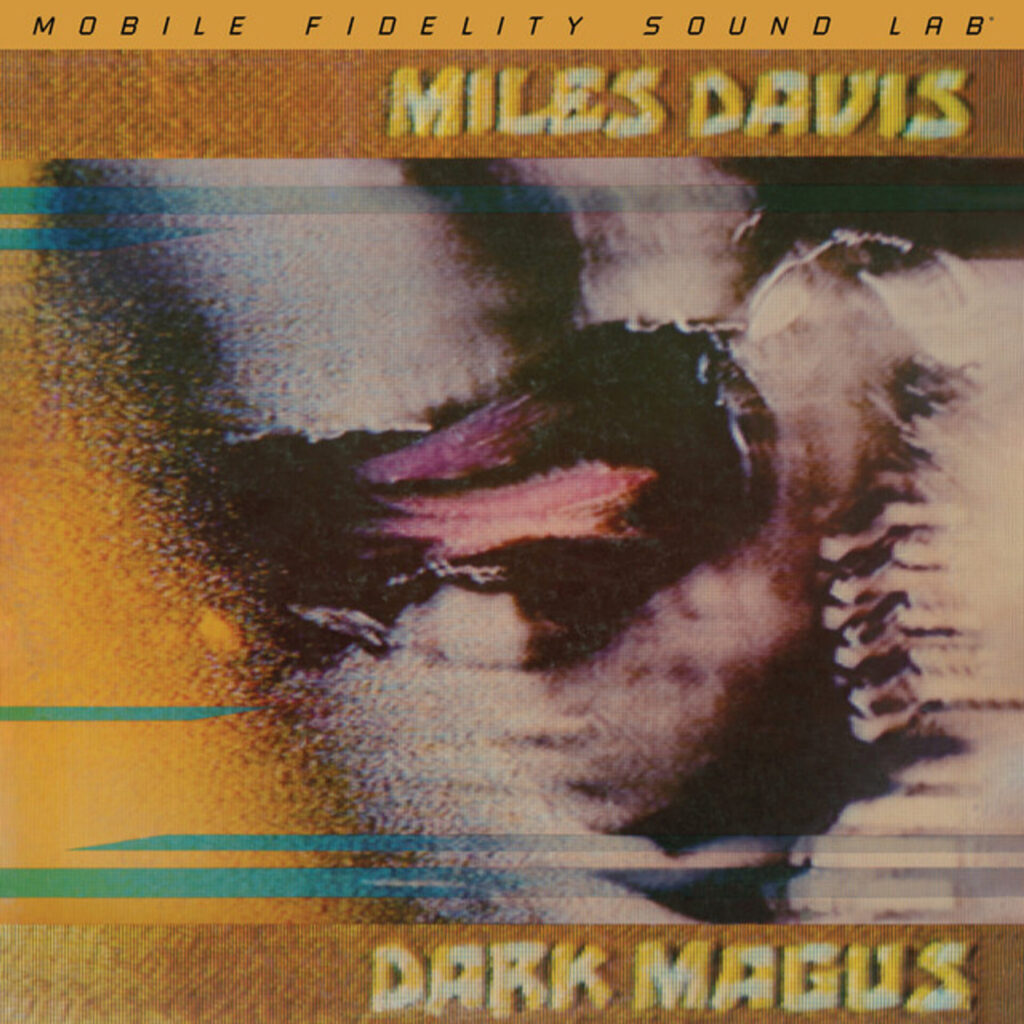

There are, surely, only two key factors that really determine whether a reissue is worthwhile. The first is if the music itself demands reintroduction, reinterpretation or reassessment; the second is whether or not the new presentation it is being given makes that easier, and improves upon earlier versions. In the case of Mobile Fidelity Sound Lab’s new vinyl pressing of Miles Davis‘s Dark Magus, both these boxes are ticked – the former emphatically (if somewhat controversially), the latter, perhaps, with some small but important caveats.

Mobile Fidelity are probably the best-known brand among the growing number of so-called audiophile labels whose business relies on striking deals to remaster and reissue what are intended to be definitive versions of catalogue albums. Alongside the likes of Analogue Productions, Speakers Corner or Friday Music, as well as imprints such as the Concord-owned Craft Recordings or Blue Note’s Tone Poet series which are restricted to specific catalogues, MoFi have helped develop and sustain a rarefied market in which collectors are happy (enough) to drop forty or fifty quid on what, for many of them, will likely be anywhere from their third to their thirteenth pressing of an album, confident that, at last, this copy will be the one that reveals details never before heard, offering a new connection to the music that will mainline the artist’s intended impressions and expressions into the listener’s head with every last bit of obstruction, obstacle and obfuscation sheared away.

In practice, of course, there’s always room for improvement – and MoFi, with its Original Master Recording range and its Ultradisc One-Step plating process, has wasted no opportunity to offer the same. Despite suffering a backlash in 2022 after a digital stage in their remastering procedure was revealed – to the horror of analogue obsessives, and at the eventual cost of around $25m following a class-action lawsuit from aggrieved customers – the imprint seems to have managed to clear the air and restabilise its listing reputation. Collectors continue to argue whether a MoFi or a Speakers Corner pressing of this or that album is superior, but few seem dissatisfied with any of the imprint’s Miles Davis reissues. Versions released in the Original Master Recording range of most of the “second great quintet” albums – Miles Smiles, Sorcerer, Nefertiti, Miles In The Sky and Filles De Kilimanjaro – are widely acclaimed as outstanding pressings of essential releases. They offer great clarity; rich detail; a massive soundstage; enhanced separation (without the clinical feel or ‘coldness’ this often implies or risks introducing); and bass with depth, presence, warmth and precision that is balanced so as never to overwhelm. Reissues in the same series of In A Silent Way, Bitches Brew, A Tribute To Jack Johnson and On The Corner are definitive: at least for now. An Ultradisc One-Step boxed edition of Bitches Brew is in the works, available for pre-order on MoFi.com for anyone willing to bet that its $125 asking price will provide sufficient improvement over the OMR version (still available for $59.99) to justify what, for most buyers, will not be a price differential but a full additional spend.

Aside from a remaster of the 1965 New York Philharmonic Hall performance released as My Funny Valentine, MoFi has been slow to deploy its technology to Davis live albums. But that has changed, and in dramatic fashion. A pressing of Black Beauty is imminent, but the first to arrive is perhaps the most contentious LP even in Davis’s polarising discography. Dark Magus is a demanding starting point in what could (should?) end up being a string of potentially revelatory re-releases – and, as befits a release presumably intended to put down a marker, the results are certainly impressive: though to what degree will depend on the quality of the system being used to play the record. Personal experience suggests a moving-coil cartridge is an absolute minimum requirement: even the best moving magnet will not be capable of the measuring the extra information in the groove with sufficient accuracy to reveal the additional detail and nuance. But if your system has sufficient capability, the rewards can be rich indeed. In direct comparison with the best currently available alternative – the 2016 Music On Vinyl pressing – and with a CD copy, the MoFi Dark Magus sounds clearer without any individual sonic element ever becoming too crisply defined. Individual details that otherwise often get buried in the complicated soundbed stand here artfully revealed without being spotlit. Like the best remastered reissues – Giles Martin’s revamp of Abbey Road, for instance; Craft’s Small Batch release of Hot Buttered Soul; Be With Records’ outstanding Lewis Taylor LPs – the remastering acts like a kind of spring cleaning: the dust is brushed away, the shine is burnished until it glows, but the patina that is essential to the character of the whole is left intact and undisturbed.

Still, it remains a curious choice for a first step into late-period live Miles, but that bravery may be telling. Dark Magus was recorded in Carnegie Hall in 1974 with an experimental outfit – the line-up that played that night would never perform together again – and, right the way back to the sleeve note written by saxophonist Dave Liebman and included when the album was first released (in Japan in 1977), it’s clear that even those members of the band canvassed on the subject don’t believe this was one of their better nights. Carnegie Hall, a venue perfect for orchestras and acoustic music, was apparently a shocking environment to play loud, amplified instruments in: the band struggled to hear one another and relied more than usually on visual cues from their leader. Moreover, Davis apparently turned up late, and decided to add a second saxophonist, tenor player Azar Lawrence, and a third guitarist, Dominique Gaumont, to the second half of the show, much to the rest of the band’s surprise. The resultant sprawl of music, split into extended and only partly improvised sequences spread over four sides of vinyl and given titles that are the numbers one to four in Swahili, is widely considered to be the most dense, forbidding and impenetrable of Davis’s career – the point where his quest for the experimental ran out of road, the sound of a restive team on a creative voyage embarked upon decades earlier finally running aground.

That, though, is far from the full story. In his autobiography, Davis described this band (well: maybe not including Lawrence) as one of the best he’d ever had, and lamented that it was not better represented on record. The reviews of the gigs around this time were uniformly dismissive, sometimes angrily so – but the recordings – Dark Magus very much included – give ample evidence that the audiences who showed up enjoyed them more than a bit. And just because the band members might (admittedly, with access to way more data to support the notion than anyone else will ever have) believe the Carnegie Hall gig to have been a sub-par performance, that’s no reason to question the merit of the music captured here. Rather than a dead end, Dark Magus seems today like a transition: perhaps it’s only because we tend to want to think of creative progression in linear terms that we struggle sometimes to hear this performance in that way. Sonically, in the music’s density, ferocity and volume, the band went further here than we would hear them going a few weeks later, on the Japanese gigs released as the blistering double-albums Agharta and Pangaea. Perhaps as a consequence of the limitations imposed by the venue and the on-stage sound, there are breaks, ruptures and discontinuities – moments where all the instruments drop out, presumably on Davis’s signalled instruction, only to leave percussionist James Mtume’s nervy conga chatter or a solo from Liebman, Cosey or Gaumont holding the fort, compounding the difficulties some listeners will encounter but also providing a sense of a band in transition, wrestling with this new music and how best to play it, taking brief moments to catch their breath and rebuild their stamina before diving back in to the battle. However we choose to interpret it as listeners, it’s clear the extremities explored here were never considered as the farthest reach of where the band could go: and what came after the Carnegie Hall, while it might sometimes sound like a reining-in, is really just the sound of the band taking a different path on that never-ending climb to a summit that was always in sight yet destined never to be reached.

Beyond the kind of plaudits that inevitably coalesce around spiky and supposedly “difficult” records by artists otherwise widely acclaimed – such as those Nick Cave and Jim Sclavunos gave tQ’s John Doran a decade ago or Jah Wobble telling late-period Davis scholar Paul Tingen that Dark Magus was a profound and key early influence on PiL – this album’s impact is perhaps best measured at some remove. You can hear its aural after-image not so much in records that sound like it – because, truly, there aren’t many that can match its edge-of-chaos blend of virtuosity, murk, polyrhythmic intensity and feral, aggressive energy – but in its absolute fearlessness, and the way the best of today’s musicians, whether they acknowledge its influence or not, feel free to go wherever their music and their muse may lead them.

While perhaps it’s wise to question the connections the mind forms between different things it has to consider over a relatively short timeframe as nothing much more useful than observation of coincidence, it nonetheless still feels worth noting a few echoes heard during the time this piece has been percolating. These are not so much of the music contained on Dark Magus but of the determination the musicians on it evidently had to push themselves and their art into somewhere new not just without compromise but without allowing any fear (of failure; of negative responses; of their infamously unforgiving leader; or, indeed, of anything else) to influence them. It’s there every Thursday night at Jazz Re:freshed’s reliably excellent London residency at 91 Living Room on Brick Lane, most recently in the person of keyboardist David Kofi and his brilliant young band who appear to view the whole of the history of improvised music as their palette and who pick and choose their musical colours with judicious care and impudent inspiration. It was there on the stage of Deptford’s Albany a few weeks ago when Dave Okumu and the Seven Generations turned an anti-racist fundraiser into a euphoric future-music masterclass. It was even there on 1 March at the Hammersmith Apollo when Sturgill Simpson‘s outstanding band walked out at 8pm, plugged in, knuckled down, and proceeded to play without pause for the next two-and-three-quarter hours, the set veering from electric bluegrass to improvised southern soul via covers of The Doors, Led Zeppelin and ‘Purple Rain’.

While you’d expect that all those performers would be aware of this record and certainly to have some views on Davis and his work more broadly, there’s no evidence to hand that suggests this record has played a direct part in any of their personal or collective development. Yet the emotional, creative and psychological territories the album maps out are the same ones any artist willing to ignore boundaries will inevitably end up exploring. The LP may not have redrawn those charts, but it has helped enlarge their scope. And so those echoes will be there tonight, tomorrow, next week and next year, any time you’re lucky enough to be a room with an artist who has learned, whether directly or indirectly, Dark Magus‘ most important lessons.