In 1956, Elise Cowen turned up for her job as a typist at a New York broadcaster, only to be told she’d been sacked. When she asked why, a colleague advised her: “Why don’t you leave like a good girl?” Cowen persisted, demanding an explanation, before the cops arrived and manhandled her off the premises, punching her in the stomach on the way out. Shaken, she phoned her father who replied, “This will kill your mother.” In her memoir Minor Characters, her friend Joyce Johnson recalled Cowen leaving for San Francisco not long after the conversation. Elise would go on to become one of the most intriguing and forgotten of the Beat Generation poets. She would also go on to throw herself through the seventh-floor window of her parents’ high-rise apartment at the age of 28.

Around the time Cowen was being driven out of New York, across the city on Long Island, a teenage Lou Reed was seeking refuge (“despite all the computations…”) in the doo-wop, R&B and rock & roll he heard on the radio, singing and playing along on a cheap guitar he’d had since he was nine. They were similar in ways, Cowen and Reed – young, hungry intellectuals from well-off Jewish backgrounds, socially awkward, bisexual, adventurous in terms of hedonistic pleasures and transgressive culture, and both facing immense familial and societal pressure to conform. There were significant differences, of course, with the Beat poet Gregory Corso later pointing out, “In the 50s, if you were male, you could be a rebel, but if you were female, your families had you locked up.” This was true – Cowen would be institutionalised and, after she died, her parents would arrange for her writings to be disposed of, in order to erase the truth and pain of who she had been – but it was not the whole truth. For one thing, people of all description, outside ‘respectable’ circles, were forced then to live under colossal constraints in innumerable ways. For another, young male rebels were locked up, even well-off ones, as Lou Reed would find out, consigned to a psychiatric hospital for juvenile transgressions and depression where he underwent electro-shock, gay aversion and drug therapies. “They put the thing down your throat so that you don’t swallow your tongue and they put electrodes on your head,” Reed remembered, as quoted in the punk oral history Please Kill Me. “That was recommended in Rockland County to discourage homosexual feelings. The effect is that you lose your memory and become a vegetable. You can’t read a book because you get to page 17 and have to go right back to page one again.”

This cure was a symptom of an underlying sickness; the ills of an age internalised and medicalised. It was conducted, it was claimed, under the guise of support, to cure Reed and Cowen and those like them of being gay, unstable, sad or simply different. In hindsight, it showed the abnormal behind the supposed normality of the times, the dysfunctional within the functions of respectable US society. These were days, after all, of segregation, the Second Red Scare, Cointelpro, MKUltra, and so on. It only becomes apparent how thin the ice is when people begin to fall through it.

Cowen’s middle name was Nada. Joyce Johnson remembered her taking “a certain melancholy pride” in having a name that meant ‘nothing’. This seems the last and most substantive link to Lou Reed, an artist who revelled in ambivalence up to and including callous nihilism. “If you said, ‘who did you like?’ I liked nobody” he told Joe Smith. The iconoclastic ‘Year Zero’ side of punk rock was clearly influenced by Reed’s belligerence, except that he (like they) did like somebody. His wife, the mighty Laurie Anderson, let it slip at Reed’s posthumous induction into The Rock & Roll Hall Of Fame, “He’s here with his heroes, Otis and Dion. He’s here with B.B. King who he loved and admired, Aretha who he saw many times, his dear friend Doc Pomus who taught him so much…”

The close-up newsprint portrait on the cover of Words & Music, May 1965 is significant then because it suggests that Reed was made up of molecular parts, not just of his experiences, talents and idiosyncrasies but also his influences. To try to understand Lou Reed, we have to begin then not with the heights and depths of Transformer or Berlin, not with the debauched street poet of the 70s or the contrary elder statesman of his final years, but with the world in which Reed grew up, one he was always looking back to and never really wanted to entirely escape. To understand Lou Reed, we have to begin not with the contemporary of Bowie or the godfather of punk but rather as a shadow of Dion’s ‘The Wanderer’, “I roam from town to town… I’m going nowhere”. We have to begin where Lou came from and where he always saw himself belonging. If you listen to Reed’s first attempt at a hit, ‘So Blue’ by The Jades, you’ll hear that world instantly. To understand Lou Reed requires looking less at where he ended up and more at what was driving him there in the first place.

Not long after his death in 2013, a package was found containing reel-to-reel demos Reed had sent himself in the spring of 1965, as a way of establishing copyright. Forgotten for decades, Words & Music, May 1965 is effectively a time capsule and an insight into the embryonic Velvet Underground. The title is significant. Reed repeatedly claimed he was trying “to elevate the rock & roll song, and take it where it hadn’t been taken before.” He did so by focusing first on the words, aiming specifically “to bring the sensitivities of the novel to rock music.” There would be a cost, however, for writing about how some people actually live, a cost for introducing the vérité that could be seen on the street, and in jazz, blues, cabaret and literature for decades (Nelson Algren’s The Man With The Golden Arm, for instance, had been published back in 1949). It was a classic case of shooting the messenger. “The other thing that killed me was stuff like this had been in novels so long, it was like nothing.” Reed told Joe Smith, “I write a song called ‘Heroin’, you would have thought that I murdered the Pope or something. It should have been, ‘now we can get a lot of people who have talent for writing and everything into rock & roll. We’ll all write about really adult stuff.’ That was what I wanted to do, is write rock and roll that you could listen to as you got older, and it wouldn’t lose anything; it would be timeless, in the subject matter and the literacy of the lyrics.” Reed would point out with pride and a touch of incredulity that he’d written ‘Heroin’ around the time The Beatles were working on ‘I Want To Hold Your Hand.’

The romantic idea of Lou Reed as a kind of psychopomp venturing into the underworld has to be balanced with the earthy salacious journalistic aspect of his writing, a quality which partly explains Reed’s turbulent relationship with the press. In his songs about drug use, he does not shy away from feelings of elation (“and I feel just like Jesus’ son”) but there are also stark admissions of the expense (“feel sick and dirty, more dead than alive”). Eros is there in his songs but so too is Thanatos, what Sigmund Freud called ‘the death drive’ in The Pleasure Principle. In the end, Reed is ambivalent (“well, I guess that I just don’t know”), drifting somewhere between agony and ecstasy, which set him at odds with the press who wanted, as he recognised, a martyr or a scapegoat. He knew this because it had happened many times already in literature (Byron, Baudelaire, Poe, Wilde etc).

Seeking a similar route through his songs, for Lou Reed books were a way of escaping into reality. Though a student of literature, he never became cloistered within it. He had a talent for courting expulsion. He was dyslexic and avoided long passages of reading. And he had the brilliant disaster that was Delmore Schwartz for a teacher. So, while there is an undeniably literary feel and structure to his songwriting, and he has a superior attitude, Reed’s work never seems bookish. His adaptation of ‘Venus In Furs’, from Leopold von Sacher-Masoch’s book, feels cinematic if anything, and while the ‘thousand years ago’ reverie of ‘Heroin’ owes something to Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s ‘Kubla Khan’, it is also escapes the page. Schwartz helped encourage what was already there – Reed’s dry and acutely observant style, his characterful miniatures (later glimpsed in ‘Walk On The Wild Side’ and ‘Chelsea Girls’), his desire to write about things, scenes and people that had been deemed unworthy, the iceberg effect employed in ‘Waiting For The Man’ and so on. Schwartz complained about how trite the lyrics of songs were on the jukebox where they drank together, between conversations about James Joyce and W.B. Yeats. He raised a challenge in Lou; write a song that honours reality by looking it square in its face. He also taught Reed about life, given Schwartz was a living embodiment of the wasteful philistinism of publishing and of a human being’s capacity for self-sabotage. While it could be claimed Lou Reed belonged to the poète maudit (‘cursed poet’) tradition, and his life was certainly colourful and transgressive enough, it was Schwartz who really belonged to that lineage, dying drunk and washed-up in the Chelsea Hotel.

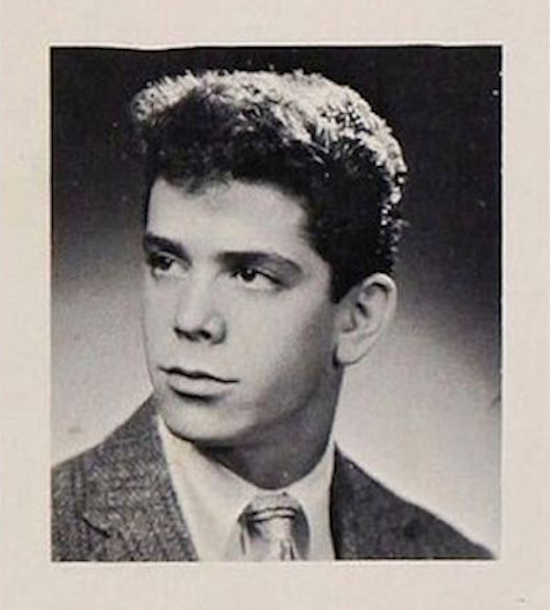

Lou Reed’s high school yearbook photo. Credit Wikimedia Commons

Reed, by contrast, was cursed-adjacent, a watcher as much as a participant. “Look, put all the songs together and it’s certainly an autobiography” he admitted to Chris Roberts, “It’s just not necessarily mine. I write about other people, tell stories, always did.” You always got the sense Reed would make it through alive, unlike those he sang about. There’s an honesty in his songs that can look like callousness in a certain light. He never perpetuates the lie that choosing a different path through life is costless. He didn’t prettify or condemn what he saw and lived through, seeing the deceit in both. He just said it like it is. The same year these demos were recorded, Reed wrote to Schwartz, perhaps not entirely conscious that Schwartz (“the greatest man I ever met”) was one of those of whom he spoke, “NY has so many sad, sick people and I have a knack for meeting them. They try to drag you down with them. If you’re weak, NY has many outlets. I can’t resist peering, probing, sometimes participating, sometimes going right to the edge before sidestepping. Finding viciousness in yourself and that fantastic killer urge and worse yet having the opportunity presented before you is certainly interesting. Interesting is not the word.”

The second part of the equation, music, would be bolstered immeasurably by the unlikely appearance of a brilliant young musician from a Welsh mining village. At the time, Reed was churning out soundalike tunes for a publishing company, a kind of subterranean Tin Pan Alley. It was there he met John Cale, who had left the valleys and a childhood scarred by sexual abuse and religious fervour and escaped to New York. The pair had the ignominious task of working together on a dance flop called ‘The Ostrich’. They would busk together under the piano mural of The Baby Grand bar in Harlem. Reed would move in to share Cale’s Lower East Side apartment, as Reed related to Nat Finkelstein, adding an extra dimension to the newsprint theme of this album. “We were living together in a thirty-dollar-a-month apartment, and we really didn’t have any money. We used to eat oatmeal all day and all night and give blood among other things [for cash], or pose for these nickel or fifteen cent tabloids they have every week. And when I posed for them, my picture came out and it said I was a sex-maniac killer and that I had killed fourteen children and had tape recorded it and played it in a barn in Kansas at midnight. And when John’s picture came out in the paper, it said he had killed his lover because his lover was going to marry his sister, and he didn’t want his sister to marry a fag.”

One of the most intriguing features of Words & Music, May 1965 is that it demonstrates what John Cale brought to The Velvet Underground, through its absence. Cale appears throughout, harmonising and jesting with Reed, but his ability to ignite Lou’s songs is not yet evident. The infernal orgiastic drones he’d bring to ‘Venus In Furs’ or the music box dreaminess of ‘Sunday Morning’ is nowhere to be found. It’s remarkable how far ahead of his time Cale was, as demonstrated by his scarcely believable 1964 track ‘Loop’ or his membership of the Theatre of Eternal Music with La Monte Young and others. That experimentalism is absent on these demos but you get the sense that Cale always leant towards the playful and fluid rather than pretentious side of avant-garde music (he was the son of a miner after all). You can see this in his early appearance playing Erik Satie’s ‘Vexations’ on the I’ve Got A Secret show, and you can hear it on these demos.

While Cale was a much more accomplished musician than Reed, the dichotomy of sophisticate meets amateur would be overstating the point. Cale had long been attracted to the dynamism of rock and was inspired by the changes Bob Dylan and The Beatles were beginning to accomplish. While he would later deadpan, “One chord is fine. Two chords are pushing it. Three chords and you’re into jazz,” Reed was steeped in jazz, especially the adventures of Ornette Coleman, and had had his own radio show Excursion On A Wobbly Rail, named after the album by The Cecil Taylor Quartet, before he was kicked off the air. Cale brought an inventiveness and a palette that Reed lacked, while Reed provided a firm bedrock that could be built upon. Reed was able to structure Cale’s experimentalism and make it palatable, while Cale stopped Reed slipping back into his comfort zone ¬– the country-tinged Dylanesque folksiness and amphetamine boogies evident in these demos. They freed themselves by reining each other in.

Juvenilia can be an underrated thing. Some of the most interesting art is created before artists find themselves or their formulas, when they have the naivety and space to make mistakes, before the mask becomes the face. At least half the album here consists of curious cul-de-sacs. There’s a feeling of relief listening to ‘Buttercup Song’, an asexual cautionary tale wrapped in an ale-swilling sea shanty, that they did not pursue this route further, but there’s also a not-without-charm WTF novelty to it as well. For a band so synonymous with aloof cool, there’s unexpected humour here, admittedly misanthropic, such as ‘Walk Alone’ with its “When you make love, you know you gotta make it alone” refrain. It’s not quite the hilarity you find in the toxic speedfreak improv of 1978’s Take No Prisoners but it’s light-hearted, goofy and surprising from a duo usually impassive behind their shades. Some of the demos are throwaway off-cuts for sure, showing that the perfection of their debut needed lots of judicious sculpture, but they also exhibit a roaming quality, a spirit trying to align with itself, and the trying-on of costumes, which, for all his monochrome minimalism, Reed never quite relinquished.

The first signs of Reed’s street swagger can be found on ‘Stockpile’ but while unquestionably cool, like ‘Buzz Buzz Buzz’, it never escapes its Chuck Berry imitations. Attempts at Everly Brothers harmonies abound. In spite of the scorn that Reed would later pour on Bob Dylan, the latter is all over these demos from the cover of ‘Don’t Think Twice’ to the sub-‘Just Like A Woman’ of ‘Too Late’ and the flops-ashore-wheezing harmonica solo on ‘I’m Waiting for The Man’. Far from the torch song on Reed’s burnt-out cabaret album Berlin, ‘Men of Good Fortune’ taps into the same Child Ballads goldmine that Dylan utilised in his early folk years. ‘Wrap Your Troubles In Dreams’ meanwhile has a sparse monkish feel (an approach you can also hear on the Peel Slowly And See box set, on Cale’s medieval demo of ‘Venus In Furs’) as opposed to the frilly baroque arrangement they later gifted Nico.

The other half of the album consists of new-born masterpieces. It’s strange to hear ‘Heroin’ begin as a lazy country-blues stroll but its force is still there in the croaking whisper of Reed’s voice that builds into a frenzied gallop, words telescoping into each other, and then returns to a restless drift. ‘I’m Waiting For The Man’ lacks the fuzzed-out propulsive urban clatter of their debut, sounding more like a troubadour on dusty highway rather than an antihero in a squalid alleyway, but its structure is intact. The late-night yearning of ‘Pale Blue Eyes’ is already in place even if the lyrics have yet to fully form. The path ahead is discernible.

What lay ahead was wondrous and wasteful. Toying at first with The Warlocks, Reed and Cale’s group took their name from Mike Leigh’s The Velvet Underground, a voyeuristic book “on the sexual corruption of our age” that a friend had found lying on the street. Sterling Morrison joined, and Angus MacLise, a somewhat esoteric figure who would turn up for gigs on the wrong day and ended up dying in Kathmandu, was replaced on drums by Moe Tucker with her perfect restraint. The band got kicked off a residency for playing cacophonies but gained the attention of Andy Warhol and flourished, briefly, as part of his Factory. The Velvet Underground & Nico dropped immediately prior to the Summer Of Love. They became the counterculture to the counterculture.

Even in the halcyon days of the Exploding Plastic Inevitable and White Light/White Heat, Reed was uneasy. The cynicism they showed to everyone outside their scene began to be directed inward. Nico was sidelined and they effectively lost Warhol to an assassination attempt by Valerie Solanas (though he survived, the artist was never the same again). Reed forced the exit of Cale and was free to fall back into his default grooves. Though the Velvets third album is entrancing (their best in my opinion) and Loaded sounds like half the songs could have been hit singles, there was still a lingering sense, post-Cale, of what could’ve been.

The Velvet Underground with Nico, 1966. Credit Wikimedia Commons

With listeners split between worshippers and jurors, Reed would go on to become an icon and a monster, capable of great beauty (Coney Island Baby for example) and both real-life and audio horrors. The commercial failure of The Velvet Underground burned him to the extent that when the success of Transformer came, he was already jaded, and would go on to snatch defeat from the jaws of victory numerous times (Cale ploughed his own unique fascinating path). It’s questionable whether it was flattering or frustrating in Reed’s eyes that, as Brian Eno put it, hardly anyone bought The Velvet Underground And Nico but everyone who did went on to form a band. There’s a sense that Reed never quite fitted in, though he tried, even among outsiders; there was something in him that prevented it, an awkwardness alongside the coolness and the cruelty that fuelled his work.

Words & Music, May 1965 has a comparatively innocent quality. Both Reed and Cale had already experienced first-hand what authority figures were capable of. They had also seen the virtuosity and self-destruction the young misfits of their scenes were capable of. Reed was already well-schooled in the New York gay scene, at a time of immense risk and requisite courage, and both were trying to eke out a living against the odds. The costs of existing authentically and adventurously were never denied in their songs, partly because neither of them had been granted the luxury of being naive. Words & Music, May 1965 has the bittersweet taste of what feels like endless possibilities but which we know now, viewing from the other side of history, is always inevitably finite. These songs hint at how clumsy, depraved and glorious life and art can get. And yet they sound so young on these demos. You are hearing Lou Reed before he became Lou Reed, and John Cale before he became John Cale. You are hearing them before they did us the blessing of opening Pandora’s Box.

Lou Reed’s Words & Music, May 1965 is out now via Light In The Attic