The opening bars of ‘The Death And Resurrection Show’ indicate alchemy at work, and within sixty seconds it becomes clear why Killing Joke anointed Dave Grohl as drummer on their 11th studio album. The rhythm is emphatic, like two military swagger sticks descending from an empyrean height, blurring with the speed of attack. Each beat is a sonic exclamation mark — and that’s even before the whole kit kicks in.

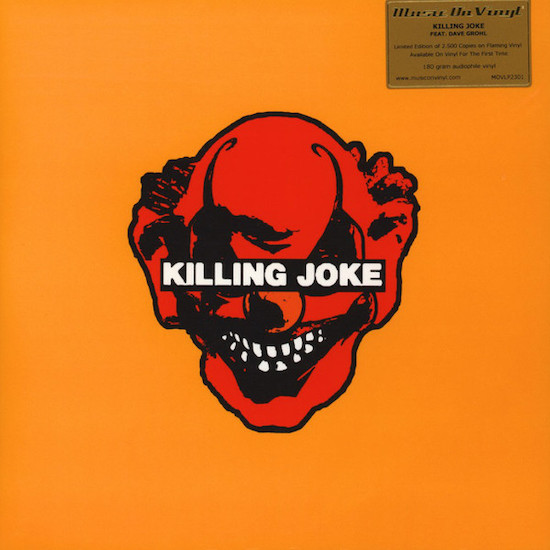

“Assemble different drummers,” chants Jaz Coleman in a threatening monotone, a line that had been a strategy in the early stages of the album’s conception. Killing Joke’s second eponymous LP, once under the working title of Axis Of Evil given its strong political themes related to the ongoing second Iraq War, was supposed to feature three different drummers who’d been influenced by Killing Joke — a kind of creative virtuous circle in the absence of a full time member behind the drum kit at that point. System Of A Down’s John Dolmayan had already recorded three or four tracks, and Tool’s Danny Carey had also been sounded out, though the chemistry between the Nirvana drummer and Killing Joke was such that it would have been foolhardy to make the record any other way. What made this collaboration all the more mouthwatering was that Killing Joke and Nirvana had history.

Unless you’ve crawled out from under a rock, then you’re probably aware to some degree of the bad blood that was caused by Nirvana, and specifically Kurt Cobain, stealing and only slightly rearranging the riff to ‘Eighties’ on the 1991 hit single ‘Come As You Are’. Killing Joke might have been justifiably annoyed — on top of the similar interpolation, both guitar lines were drenched in chorus. That said, ‘Eighties’ didn’t sound too dissimilar to 1982’s ‘Life Goes On’ by The Damned — a line of attack Nirvana’s lawyers would have surely used had it ever ended up in court. Cobain’s suicide in 1994 put an end to litigation, though it still would have been on Grohl and Coleman’s minds when they agreed to meet in a bar in New Zealand in early 2003.

The singer, who lives between NZ and Prague in the Czech Republic, turned up in a dog collar — in case Grohl wasn’t terrified enough. The pair got drunk together and at one point rolled down a hill during their bonding session, with Coleman apparently on his hands and knees in the early hours attempting to bite the legs of a pair of Bush supporters who’d gone to New Zealand on holiday. Most importantly, Jaz popped the question to Dave and Dave said yes, agreeing to play on Killing Joke’s new album and, so the story goes, refusing to take any fee for his endeavours. That waiver might have been perceived to settle the “debt”, though Grohl never made any money from publishing on ‘Come As You Are’, even if he was aware of where it had been lifted from as a massive fan of the band growing up.

What he did gain from the experience, aside from playing with his boyhood idols, was reaching the absolute pinnacle of his recorded output on the eponymous album Killing Joke themselves now refer to as 2003. It’s a bold claim, but the suggestion that Killing Joke is the best thing Dave Grohl ever played on, made considerably better by his skills and power, is worthy of examination.

Grohl may have made his name with Nirvana but nothing by the three-piece was ever as heavy or robust as ‘Asteroid’, a track that could block out the sun and wipe out all life on earth. The clattering snare report echoing the work of Bad Brains’ Earl Hudson that blasts ‘Smells Like Teen Spirit’ off might be Grohl’s calling card, but he’s still capable of much more. The quiet/ loud dynamic of Nevermind, heavily inspired by Pixies, hardcore and, perhaps slightly unusually for a grunge band, the metronomic 4/4 of disco and soul, don’t really call for him to push himself in the same way he does on 2003. Nirvana were arguably a great band who never worked with the right producer for the record they were working on: Nevermind sounds too compressed, while Steve Albini’s no frills approach on In Utero has been pushed in the opposite direction, perhaps in reaction to Butch Vig’s sheen, and is a little too dry for me to fully lose myself in.

From the start Killing Joke cast a much wider net than Nirvana drawing from the fields of reggae, disco, dub, punk, pop, funk and heavy metal. In particular they were fans of kosmische and worked with the estimable Conny Plank on their third album, 1982’s Revelations, and hypnotic, repetitive drones combined with an atavistic, so-called tribal rhythmic influence is a core attribute of their work, and is very much in evidence on Killing Joke, allowing Grohl to push beyond the event horizon on trance-inducing, drum & bass influenced tracks such as ‘Implant’.

Since early Malicious Damage singles ‘Turn To Red’ and ‘Nervous System’ in 1979, KJ have always displayed a genuine and deep affinity for dub, and, unsurprisingly, this resurfaces on 2003. This affect is accentuated by producer, Gang Of Four’s Andy Gill. Gill not only brought experience and edge, he also programmed the drums as surrogate place markers, which would be wiped at a later date when the acoustic drums were added. In the end, Grohl was so impressed with the patterns Gill created on drum machine, that he simulated those parts as much as possible in his playing. That added element of premeditated thought carried out by a drummer at the top of his game gives the record a searing urgency.

Killing Joke recorded their parts at Gill’s Beauchamp Building studio in East London, and Grohl added drums later at the legendary Grand Master studio in Los Angeles. It’s unusual, but not unheard of, to put drums on after the core of the music, though in modern recording, where everything is layered, the rhythm section usually goes first. I recall talking to Tony Allen about how he laid the drums over Sebastien Tellier’s ‘La Ritournelle’ when all the music had already been laid down, a surprise given how integral the beat is to that chanson. It’s not necessarily easy to align everything in that order, as the drums are often the pivot point upon which everything else depends.

Killing Joke tried it themselves on 1988’s Outside The Gate, essentially a Jaz Coleman solo album during a period of intense narcissism and drug-addled delusion which eventually led to the frontman having a breakdown. Big Paul Ferguson laid his drums down last, but he hated Coleman so much at the time that he refused to listen to either his keyboards or singing, which would provide the prompts he needed. The bizarre syncopation created meant his drumming was unusable, and a record that was already way over budget continued to run up excessive expenses. The band disintegrated soon after, and Ferguson didn’t return to the fold again until 2010’s Absolute Dissent.

Coleman and guitarist Geordie Walker flew over to L.A. to oversee Grohl’s sessions at the Grand Master, where they had a leisurely week in the drum room, interspersed with bong breaks, to develop the rhythm parts. According to Killing Joke biography Are You Receiving? by Jyrki Hämäläinen, they decided to layer many of the tom-tom drums and cymbals rather than record the kit live as a whole, hitting the instruments separately and spreading them out over different tracks to foster precision and eliminate bleedover. The resulting recording makes the drums sound gargantuan. With added time, Grohl was able to imbue the booming tribal delivery of Big Paul and the technical mastery of Martin Aktins, all with the added nous of Andy Gill.

It’s this team effort and savoir faire that makes 2003 Grohl’s finest hour. There have been great moments before, of course, but they pale in comparison next to the indomitable performance on tracks like ‘The Death And Resurrection Show’ and ‘Asteroid’ and, as luck would have it, Killing Joke themselves are more focused than they ever Previously had been, making for a perfect sonic storm without a second of filler.

Grohl drummed and played most of the instruments on the early Foo Fighters records, until Taylor Hawkins took the vacant drum stool to free him up as frontman, turning the alternative indie group into an AOR stadium rock behemoth. The deification of Grohl will not be halted as people clamour to bestow “the nicest guy in rock” epithet on him, but surely nobody with any sense would put Foo Fighters on par with his best work in Nirvana. Then there’s the hillbilly glam rock of Queens Of The Stone Age’s Songs For The Deaf which certainly elevated the Californian rockers to a different plain, and his metal side project Probot proved he would have made a handy Motörhead replacement had Mikkey Dee ever wanted to call it a day, but on 2003, he helped consolidate Killing Joke’s place in the metal pantheon, and blow away all the pretenders that cited the band as an influence: Ministry, Tool, Fear Factory, Rob Zombie and so on.

“Dave played Killing Joke patterns,” Coleman told the now defunct internet magazine Blistering. “In trying to become Dave Grohl, he became the drummer for Killing Joke. He worked with us, and those traditional Killing Joke tom-tom patterns that have been in our band and our style since we began. What a fucking great job he’s done, a fucking brilliant job. I’m really proud of the man.” Perhaps there’s an alternative rock universe somewhere where Dave Grohl knocked Foo Fighters on the head in 2003, and instead embarked on a lifelong mission to make other people’s records sound much better by sheer dint of him sitting behind the drum kit. A sonically appealing realm for sure.