While leafing through issues of Black Music from 1976, then the UK’s leading periodical dedicated to tracking the progress of disco, funk, reggae and soul, the reader is gifted great features on Marvin Gaye, Earth, Wind & Fire, James Brown and Bob Marley and The Wailers. It is a document of the mainstream being shaken up by American and Jamaican popular music, some with strong and newly found interest in multiple African influences. Despite nearly most of the attention being given over to Western hybrid forms, sometimes the original unprocessed source is covered. Afrobeat, from Nigeria, for example, is mentioned via a the feature on Fela Kuti, the artist who was then widely hailed as the genre’s pioneer. By that moment Kuti had released eight albums, “every one major commercial success” – which would go some way to explaining the publication’s interest. “What are the reasons for this phenomenal and increasingly global appeal?”, author Chris May wonders. “The answer lies in a space-age fusion of African and Afro-American styles.”

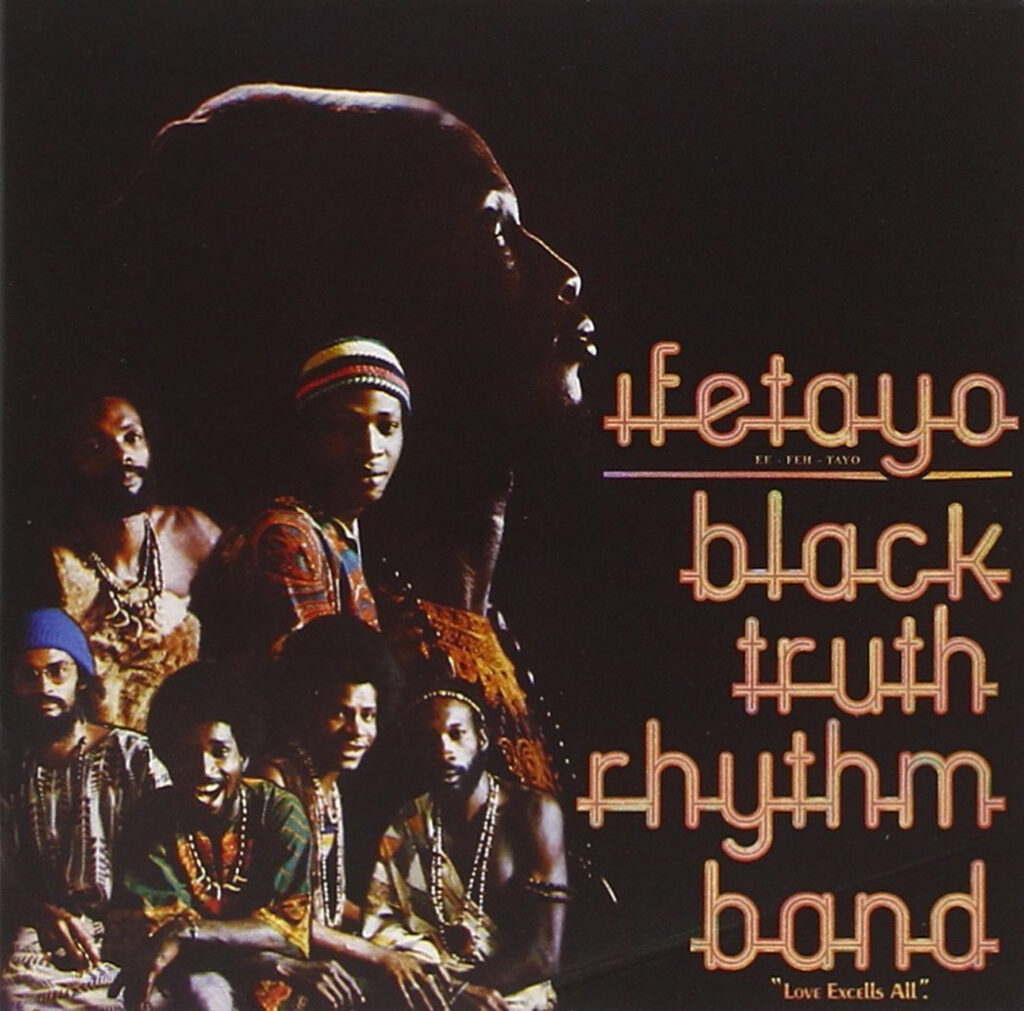

On the other side of the world from the hotbed of this emergent movement (and away from its impact in the UK and America), in the Caribbean, the Trinidadian collective Black Truth Rhythm band were also drawing inspiration from West Africa – sonically, from Nigeria, at least – and the traditional music of their homeland, seen through a diasporic, colonial prism. The name of their sole album Ifetayo is a statement in itself. From the Yoruba language, spoken in West Africa, the Caribbean and Brazil, it translates as “love excels all”. In keeping with this life-affirming title, the recording has a rich sonic texture provided by traditional instruments kalimba, congas and omele bata (Nigerian talking drum) alongside the conventional set-up.

To underline this concept the Black Truth Rhythm Band took on new names as well as dress: Dada Eleja (Kenneth Sheppard), Herbie, Ipele Jo (Ralph Bennett), Labe Ijoba (Andrew Wallace), Ogbon Iselu (Holly Cruickshank), Akowe (Earl Lewis), Oluko Imo (John Andrews) and Alafo Juto (Arthur Byron). For all aforementioned artists, except for Imo, Ifetayo was the only release. The driving force behind the project, Oluko Imo later worked on his solo projects and collaborated with Fela Kuti performing with Fela’s Egypt 80 band.

Despite the undeniable Trinidadian influence, the band didn’t quite click with a domestic market, arguably because their attention was directed towards Africa. The overwhelming popularity of reggae and the scarcity of African records on the West Indies market at that time proves this unusual choice was bold. However, if this was a gamble, it didn’t pay off and didn’t lead to any kind of success for the record; it remained largely obscure to the rest of the world despite the band’s deal with Phillips and Charlie’s Records, a hub for the Caribbean community in Brooklyn. Thus, Ifetayo had been a sought-after item until the first reissue came out on Soundway in 2011. Now, the label presents a remastered version which appears in three formats – vinyl, CD and digital – for the first time.

Around early 1976, the members of the Black Truth Rhythm Band gathered to record Love Excels All at KH Studious in Port of Spain. The line-up mentioned above formed following a series of changes where Oluko Imo was the only constant contributor and the collective’s leader. Born into a musical family, Imo soaked in the sounds of the local scene such as Trinidadian unit Bert Bailey & The Jets who blended traditional genres such as soca with mainstream American soul. Following his passion and influenced by his father and uncle (both respected musicians on the country’s scene at that time), he joined the Blue Veils, a combo which mainly covered popular North and Latin American songs with a soca and calypso twist. At that time, the artist would still introduce himself by his birth name John Andrews. He played the guitar and then became the band’s bassist and vocalist. The Blue Veils would have continued their aspiring career if not for the influence of the Black Power consciousness shift hitting Trinidad.

This Ifetayo reissue comes out two weeks before the 55th anniversary of the Black Power protest. On 26 February 1970, the students of the University of the West Indies (St. Augustine campus) went on to protest against the arrest of the Caribbean students in Montreal who had accused a professor of biology at Sir George Williams University of racial discrimination. The protest transformed from a peaceful event into a militant movement fuelled by police violence. Racial discrimination was not exclusive to Trinidad and Tobago where, according to Khafra Kambon, the Black Power activist and Emancipation Support Committee Leader, for example, people would not be able to get a job at a bank, for example, unless they were white.

Soon after the protest unfolded, a few friends of John Andrews were arrested as the country entered a state of emergency. Suddenly, the crucial musical culture and nightlife in Port of Spain, not to mention the rest of the country, were put on hold. These events led Andrews to consider his African roots and heritage afresh. He gave up his English name, becoming Oluko Imo, with a reference to Baba Imo, who conducted the meetings at the local branch of Marcus Garvey’s Universal Negro Improvement Association. Citing the Blue Veils guitarist Andre Labeijoba Wallace, Trinidad-born writer Attillah Springer wrote in her biography about Oluko Imo for Soundways: “Baba Imo was teaching us Yoruba language and drumming. It was under his guidance that we were given new African names. It was in Baba Imo’s yard that we spent time with Bertie Marshall and Rudolph Charles, who were seriously innovating with the steelpan.”

The sincere approach and excellent musicianship make Ifetayo an effortless, captivating and invigorating listen. It starts with a smooth and inviting title track where calypso-esque call-and-response singing in Yoruba and an electrifying fuzz of guitar riffs provide an instant awakening. Another example of the undeniable calypso influence is ‘Save D Musician’ addressing the troubles for the music scene that resulted from the state oppression. Swirling Afrobeat on ‘Kilimanjaro’ is a more direct reference to Nigeria and a signpost for Imo’s future collaboration with Fela Kuti. Meanwhile, bonus track ‘Imo’, dedicated to Baba Imo (not included on original LP), demonstrates, ultimately, the versatility of Black Truth Rhythm Band, striking a balance between different genres from specific regions, not to mention Black music in a Western context with dashes of funk, Motown and Northern soul. It’s also evidence of the band’s potential had it not disbanded while finally promising some longevity, as with these reissues, Ifetayo is reaching the wider audience it deserves.