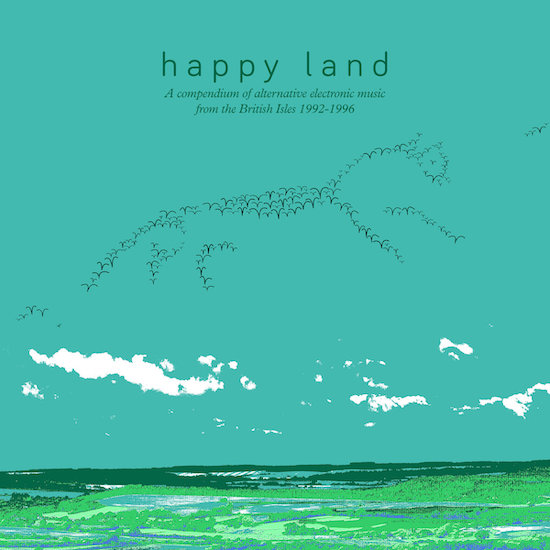

Seeing the Uffington White Horse on the cover of these compilations of British “alternative electronic music” from 1992 to 1996 absolutely floored me. I was already excited to see the name of the compiler Ed Cartwright, a former influential PR, who now manages the likes of Seth Troxler and Hercules & Love Affair: this is someone who’s managed to keep their critical faculties and enthusiasm intact even in the upper echelons of the dance music world, not someone who makes obvious choices. And this was my music, the soundtrack to finding my cultural feet in my late teens and early 20s. But then I saw the artwork and truly reeled.

Thing is, I grew up in The Vale Of The White Horse, bang in the middle of Middle England, in the southern corner of Oxfordshire, bordering Wiltshire, looked over by what older residents still called the Berkshire Downs. A bunch of my schoolmates lived in villages literally in the shadow of White Horse Hill, and the weird glyph-like horse was the emblem for our district council, so visible not just in the flesh from miles around, but printed on stationery and signs just about everywhere in everyday life. And we spent a lot of time up on that hill, in Transit vans or parents’ borrowed Peugot 205s, drinking, smoking, eating mushrooms, looking out for UFOs and listening to tapes of this music – in fact to may of the exact tracks that are collected here.

Which is exactly the sort of untethered, unofficial, unstructured setting that this music first occupied most perfectly. This was the period just post the white heat of the rave explosion, during which genres – jungle, trance, hardcore, trip hop etc – were settling into their final forms, but still melted into one another in the in-between spaces of cars, bedrooms, after parties, free festivals, spontaneous gatherings. And the landscape was an intimate part of that. Free parties, the “on a mission” ethos of driving across country to rave, and the presence of the new age traveller convoys – an intriguing / folk-devil presence through my childhood, and a first real interface with true subculture as we rode our mountain bikes up the Downs to their encampments as teens – saw to that. The social, the psychedelic and the geographic were all part of the same structure, the same ongoing rituals.

Plenty of the musicians collected here are rurally rooted. Aphex Twin (here under the Strider, B. alias from an EP on his Rephlex label) has referenced the Cornish landscape throughout his work. Plaid (two thirds of The Black Dog and Xeper) were b-boys from the open expanses of East Anglia. Matthew Herbert is from the Kent coast and cut his musical teeth in the outdoor free parties of the West Country when at Exeter University. Ultramarine are from the Essex countryside. Max Brennan (here as Fretless AZM and just Max) grew up on from the Isle of Wight. You don’t need to be a leyline-following psychogeographer, or even to see the trippy landscape artwork of the albums, to feel that connection, either: it’s all too easy to sense chalk, moss, mud, thistles, bumpy tracks and rolling hills in this music.

Structurally, some of the tracks touch on familiar dance genres. There’s some fairly slamming Detroit-indebted techno (Radioactive Lamb’s ‘Bellevedere’ on Vol 2), and Herbert and Brennan’s contributions are the kind of headsy but still soulful New York / New Jersey / Chicago house that DiY and related soundsystems were making a vital soundtrack to the English countryside. Way more, though, this music inhabits those in-between spaces. Xeper’s ‘Carceres Ex Novum’ (from The Black Dog’s Bytes album) is a weird breakbeat chug with the ghosts of rave piano riffs swirling through it. Zone Smut’s ‘Down on All 4’s’ is ultra-narcotic steppers dub full of gloopy noise and bongos. ‘Meditation’ by Syzygy – a duo featuring sometime Dr. Who composer Dominic Glynn – is nominally techno, but its angelic wordless singing and pitch-bent synth melodies have an airborne quality that’s all hillside sunrise.

This isn’t all pastoral dreaminess and rave generation optimism and futurism, though, far from it: there’s a deep darkness throughout. As Matt Anniss’s sleevenotes point out, this was a country in the midst of recession, the aftermath of Thatcherism, and a post-Castlemorton crackdown on alternative culture with the 1994 Criminal Justice Act. The track that gives the compilation its title – one of several collaborations that Ultramarine recorded with Robert Wyatt – is an oddly jaunty bit of folk-dub, but its lyrics are a sardonic parody of a Victorian patriotic song capturing the bitter ambiguity in any feeling of belonging or freedom in a land where iniquity and oppressive landowners keep control: channelling William Blake and generations of dissenters, (and, it has to be said, with a lot of the paranoia that can, sadly, tip over into Freemen On The Land conspiracy bullshit). And shot through everything, there’s an eeriness, a murk to the sounds in the depth of the dub basslines and the subliminal whirrs and chirps. It’s the fading of the bright lights of rave, the texture of rusty barbed wire and shotgun cartridges trodden into the mud, and the overpowering smell of waxy adulterated hash, body odour, cow shit and diesel fumes; it’s the bones-deep weariness of moments between hedonistic highs; and perhaps deeper still, it’s the grumbling and cantankerous spirit of the land itself, those subliminal noises flickering like the shadows around an old burial mound.

Nonetheless there is joy here too. Those dreamy melodies in ‘Meditation’, and the surging acid and murmuring voiceovers of ‘True Romance’ by the gloriously named Thunderhead The Word By Eden are as ecstatic as any record made in any style during this time. Those hillside house grooves by Herbert and Brennan retain their zoned-out funk and keep both feet on the turf even as their weirder edges are threatening to take your head somewhere else. And there’s a sense of coherence, of a culture constructing itself as it goes, of a scrappy kind of unity persevering: this is the sound of urban ravers, industrialists and Psychick Youth still in intense cultural conversation with countryfolk and the crusties of the convoy, unconsciously in touch with those deeper spirits of the land, and blearily thinking of the future.

This music isn’t obviously futuristic as such, not in the way that, say, drum&bass was at the same time. But it does sound surprisingly fresh now, for all its muddiness and stoned murk. It’s not just through the continuing careers of Aphex Twin, Herbert and Plaid that it moved forwards: the LSD-soaked, Megadog / Megatripolis zone in which a lot of this music existed helped nurture the likes of Orbital, Underworld and Leftfield. Those eerie psychogeographic echoes of Old Weird Britishness merging into dub basslines would resound through the works of Andrew Weatherall right to the end. And the dreamy free party house groove which Herbert and Brennan channel would beget talents like Atjazz, Charles Webster and Phil Asher, whose beats and textures have had global influence – even, incredibly, on the South African house music that is currently revolutionising global club sounds.

It’s clear that this music is ripe for reassessment, 30-odd (very odd) years on, now that it has become a kind of Old Weird, Britishness of its own. Matt Anniss’s own Join The Future: Bleep Techno And The Birth Of British Bass Music book (just out in expanded second edition) and compilation traces the details of the urban British collision of techno with soundystem bass that bleeds into this album via two tracks from Sheffield’s Richard H Kirk (as Cabaret Voltaire and Sandoz). The new Musique Pour La Danse compilation Bleeps, Breaks + Bass and the just-announced Richard Sen presents Dream The Dream: UK Techno, House and Breakbeat 1990-1994 dig deep into the hinterlands around this. Books and films are emerging apace about Spiral Tribe, DiY and all those other nexuses of off-grid raving.

This is not history written by the victors. It’s not the neat this-then-this-then-this narratives or sharply-delineated proprietory continuua of category-obsessed cultural librarians. It’s a long, weird dream of thousands of hours and miles of road, of pilgrimages interspersed with revelation, of magic happening in dirty places, coming back to us collectively in flashes. And for a lot of us – whether we absorbed this stuff through endless hours in vans, cellars, hillsides, or whether we are new to it – these album and all those other remembrances serve as a fantastic reminder that that culture lives and evolves in those endless, shadowy, muddy, uncertain places and times in between, too… and maybe still can?