This archival DVD release of 13 arts documentaries commissioned and produced by the Arts Council Of Great Britain represents a treasure trove that has finally been returned to a wider viewership. The timescale of these films – 1979 to 1996 – sheds new light on those who fought to create art, music, and poetry from the onset of the Thatcher government to the false dawn of New Labour. They demonstrate how, with their creativity, filmmakers and performers alike tried to make sense of the times they were living through.

What might surprise some is that for all the attention paid to an era where punk mutated into post punk and new wave, there is almost no acknowledgment of rock music within these films. Instead, attention is given over to classical music (the English/Irish composer Elizabeth Maconchy); minimalism (Steve Reich); experimental and improved music (Cornelius Cardew, the Bow Gamelan Ensemble, Max Eastley); and new forms of music emanating from African and Indian forms filtered through the prism of UK collectives like Asian Dub Foundation and Steel ‘n’ Skin. What passes for rock & roll attitude is personified by the subjects of the two landmark documentaries that dominate the collection.

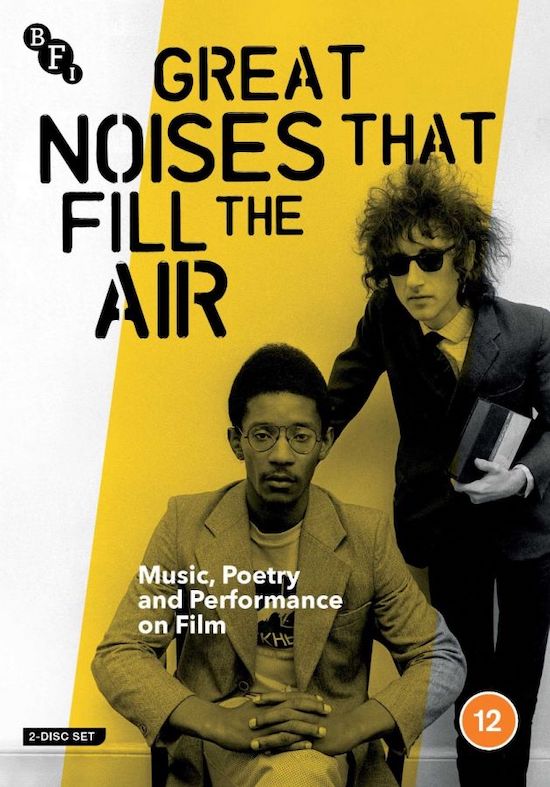

The longest films are Franco Rosso’s Dread, Beat And Blood (1979) about the poet and activist Linton Kwesi Johnson, and Nick May’s film, Ten Years In An Open Necked Shirt (1982) about the poet/performer John Cooper Clarke, Paired as they are on the cover of the DVD, the careers of both men are subtly interwoven, particularly in May’s film as they are filmed on a joint UK tour together. Rosso’s film focuses on Johnson at the heart of his community in Brixton, writing and performing locally, recording his debut album (which gives the film its title), visiting his old school in Tulse Hill, and being interviewed for various publications.

Dread Beat And Blood

Rosso captures an artist fully immersed in his environment, be it a performance at a youth club or simply shopping amongst the stalls in Brixton Market. These sequences are invaluable documents of an area that was already at the front lines of the anti-racist struggle, the streets in which people would soon rise up in rebellion. That sense of latent frustration simmers in every frame. It is Johnson himself who articulates that frustration, honing that anger into art via his poetry. His poise and control in front of any audience, be it a group of school kids or a BBC interviewer is extraordinary.

No word from his lips is wasted. In one remarkable statement, Johnson says that he found the English language ‘too sterile’ to communicate with, using instead what he describes as ‘Jamaican creole’. That sense of literally finding his voice outside of what is or isn’t acceptable language is still as sharp a critique of what passes for language or communication as there has ever been. The performance footage of Johnson is just as extraordinary, from the rumbling dub of his first recordings to his performance on the steps of a council building in Bradford at a demonstration in support of George Lindo, who was wrongly convicted for robbery. There is even a digression into an explanation of sound systems, itself a vital new ( literal) subculture of music to these shores.

Ten Years In An Open Necked Shirt

The political climate of the times is foregrounded with news reports of sectarian violence in Lebanon and references to the IRA and Rhodesia as Johnson walks the streets of Brixton. Johnson’ antipathy to the racism of both the National Front and the policies of the incoming Tory government is withering: "The Thatcher government are trying to put blacks in a position of demoralization… in this country… While I’m here, I’ll do what I can [to fight it]." The film brings some of those in the anti-racist and anti-fascist struggles of the late 70s and early 80s once again, with priceless footage of Darcus Howe and many others at work in the offices of Race Today, a magazine that Johnson supported and contributed to. With such a hard battle to fight each day, the scenes which show Johnson truly relaxed, smiling, and playing dominoes with friends, a welcome respite.

Ten Years In An Open Necked Shirt is a rather more ‘cinematic’ film, with extended sequences used to accompany what John Cooper Clarke describes as the "high octane delivery" of his poetry, creating a pleasingly dissonant series of visuals to complete recitations by Clarke’s immersive work. Filmed on tour in the North of England with Linton Kwesi Johnson, Clarke is in the first flush of cult hero success, in demand as a performer and for interviews. His charismatic persona onstage, the verbally dextrous, machine-gun-on-the-microphone attack is irresistible. His self-effacing manner offstage is both a surprise and a relief.

May allows jarring details to rise to the surface: the gum-chewing banter and bonhomie of Melody Maker journalist Patrick Humphries when speaking to Clarke disappears completely when he is confronted with the clarity and poise of Linton Kwesi Johnson’s responses; the casual homophobia of the photographer who quips that he should send a photo to Gay News when Clarke and Johnson stand close together. The performance footage of Clarke is of course great, but Johnson steals the show and the film with a devastating performance of his most harrowing poem ‘Sonny’s Lettah’. The film is also notable for a fleeting but stunning appearance by Seething Wells, AKA the late, great writer and Quietus columnist Steven Wells, performing his poem ‘Tetley Man’ in full furious cry as part of the support acts.

Clocks Of The Midnight

Even films with the slightest running times can dig the deepest and make the biggest impact. Karen Martinez’ remarkable film Chutney In Yuh Soca (1996) demonstrates the origins of Trinidadian dance music in Indian cultural traditions, its post-colonial complexities, religious and ethnic tensions and the ensuing hybridisation of the music itself all in just 21 minutes. Smita Malde’s short Strong Culture (1995) has the feel of home video footage due to her close friendship with the youthful first incarnation of Asian Dub Foundation. It is also refreshing to see and hear creative people speak in such political terms about the work they are creating who their work is for, and just as importantly, who it is directed against. Peter Blackman, the founder of the group Steel ‘n Skin is unapologetic about directing their workshops towards young black kids:

"When we work with white kids, we find that we tend to be just providing an afternoon of fun. When we work with black kids, we find that they take us far more seriously, because to them, we are representing a part of their culture, their real living culture that has been denied. So they leap at the opportunity to build as much of it as they can."

Their exuberant performances for school and youth groups take on a greater urgency once that acute and explicit statement is made.

In Margaret Williams’ film about Elizabeth Macconchy, the struggles that faced her and her female contemporaries in the 1930s are couched in both class and gender terms. Maconchy told her friend Anne Macnaghten that "if you are a nursing mother, you have to learn to compose between feeds!" However, Macnaghten makes it clear they were undaunted. Inspired by the liberatory gains for women after the First World War, but most particularly after the Russian Revolution in 1917, they begin performing their own work at the Mercury Theatre in Notting Hill. It is one of the most startling personal testimonies about the real gains made by women from collective struggle that I’ve ever seen.

The film I was most looking forward to watching was Philippe Reginiez’s Cornelius Cardew: 1936 – 1981 (1986) and it did not disappoint. The recitals from elements of his epic composition The Great Learning are impressive, as are the heartfelt tributes paid to Cardew by heavyweights such as Morton Feldman, Christian Wolff and Karlheinz Stockhausen; praise from the latter is all the more surprising given the venom Cardew directed at him in his vituperative book Stockhausen Serves Imperialism. His reputation has clearly fallen since this film but his music deserves a revival.

These films are unencumbered by explanation or celebrity fans telling you why you should care. Where there is narration, it is impactful and precise. The best use of it can be heard in the films by Simon Reynell. His film about the sound sculptor Max Eastley, Clocks Of The Midnight Hours is my favourite of the entire collection. Scenes of Eastley’s aeolian harps ringing by waterfalls are simply mesmerising, and contrast with a group including David Toop and Steve Beresford demonstrating Eastley’s ‘whirled music’, all of them wearing wicker balaclavas. The final sequence of Eastley duetting with free improvising saxophonist Evan Parker in a cave in Kent is an absolute joy to behold.

Commissioned and produced during a time of great social and political upheaval, issues of class, ethnicity, gender and identity are freely at play throughout these films. The participants do not pull their punches, their gazes dare to meet our own. At a time when arts programming is in danger once again from unreconstructed whelps like the Culture Secretary Oliver Dowden, to hear and see those who have helped shape our shared culture, from the grassroots level and upwards is hugely inspiring. These films should be essential viewing for everyone.

Postscript: In the booklet accompanying the DVD, Rodney Wilson informs us that Dread, Beat and Blood was postponed from its original slot on the BBC arts series Omnibus because it might influence the outcome of the 1979 election. It was shown at a later date.