Never let it be said that Gary Numan doesn’t care. Aside from one well-documented misfire with 1992’s Machine + Soul – an album that largely eluded his control, something for which he’s been penitent ever since – Numan is clearly obsessed by making records. In his 2020 autobiography (R)evolution, he comes across as a man preoccupied with the process, down to the tiniest of details. In the eighties, he may have fixated on dwindling chart positions and nearly lost his mind puzzling over the dearth of radio play coming his way as he slid helplessly and haplessly into bankruptcy but the long, hard slog dragging himself back from the brink was just as much driven by a monotropic obsessiveness.

Even now, when he appears to be safely back in the middle of the bed both creatively and commercially, he still amps up the pressure on himself. It is now 47-years since Tubeway Army released ‘That’s Too Bad’, his first single, he’s somehow still plagued by a lack of confidence that leads to months on end of writer’s block, self doubt consuming his every waking moment.

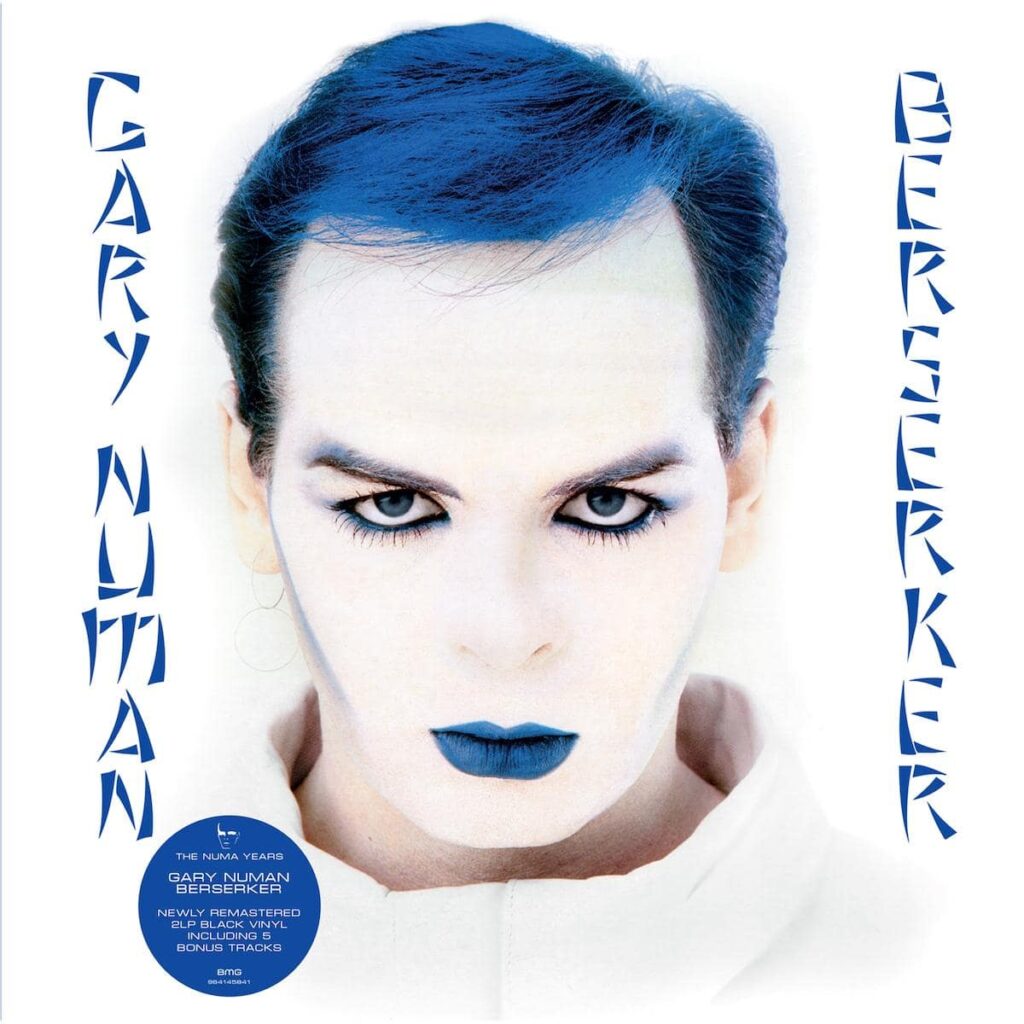

Machine + Soul is unlikely to get reevaluated any time soon, though Numan’s frustrations are understandable given how few other outright duds there are in his back catalogue. Perhaps the best of the glorious commercial disasters from his doldrums, is Berserker, the first record released on his own Numa label in 1984, after he left Beggars Banquet. The brave new world of Numa was supposed to herald an artist taking back control after five years of hitmaking with his first label – a lifetime in the pop world, especially in the 1980s. At 26 years old, he needed to halt a clear downward trajectory with something epochal, something special. In 1979, he enjoyed two number one singles and two number one albums; just five years later he was struggling to make either top 40.

Relations had soured with Beggars thanks to creative differences. It wouldn’t be overstating it to suggest that Numan’s instincts – essentially gambled upon by label founders Martin Mills and Nick Austin – had helped usher a new dawn of electronic music into the mainstream. Nevertheless, those same instincts could be erratic and, at times, his decisions seemed baffling to everyone but himself. His last three marginally successful, bass-oriented albums featuring contributions from Mick Karn and Pino Palladino had led to tensions which came to a head when a peroxide blond Numan posed in full Mad Max cosplay for the cover of Warriors when the label wanted him to pursue a more mainstream direction. Furthermore, Beggars, concerned that their charge wasn’t keeping up with electronic advances, imposed a producer on him. Both parties agreed on Bill Nelson of Be-Bop Deluxe, who was Numan’s favourite guitarist, although the pair fell out and Numan remixed the whole thing himself to everyone’s annoyance.

While he might have been through with label interference, the criticism clearly stung, because Berserker utilises the PPG Wave, a cutting edge digital synthesiser that required two additional technicians to come along and operate it while he figured out how it worked. “The PPG was the heart and soul of Berserker”, wrote Numan in (R)evolution. “Everyday in the studio was a walk into the unexpected. It was also my introduction to the world of sampling, and we spent much of our time walking around Shepperton Studios recording anything we could hit, scrape or drag. We became obsessed with trying to find the most unusual sounds and then manipulating them into something we could use musically. It was very inventive, and it was great fun.”

In the end, Mike Smith and Ian Herron aka The Wave Team would stick around for the next two albums: 1985’s The Fury and 1986’s Strange Charm, almost up to the point where the PPG had become so outmoded that Palm Products in Germany stopped its production altogether. Where Stevie Wonder had drafted in Malcolm Cecil and Robert Margouleff and their super-synthesiser T.O.N.T.O. to help him achieve arguably the greatest four album run in history, from Talking Book to Songs In The Key Of Life, Numan’s outside help brought only diminishing returns.

Moreover, if Numan was having “great fun” finding chair legs to scrape across the floor of Shepperton Studios to record, then that thrill was offset by a more troubling disturbance in his personality, with a wave of what can surely be put down to depression making its way into the songs. For an artist embarking on a new phase, Numan sounds strangely diffident on Berserker, seemingly overcome with gloom and often deferring to Tessa Niles, whose backing vocals are really at the front and centre for much of the time.

The lead song and title track even finds him appearing several bars after you might expect him to show up. He enters crooning nonchalantly with shades of David Sylvian influencing his delivery, following a fusillade of vulgar guitars and several rounds of backing vocals that metaphorically warm the stage for him. We find ourselves going around on a four chord loop for most of the song, though what feels different from recent albums is the clarity in the writing, sparse and intermittent as it is. Following the musical indulgences of the previous three albums, Gary suddenly seems to remember that less is more.

In truth, the songs on Berserker are melodically the strongest since The Pleasure Principle, even if conceptually everything is clearly a lot more nebulous. The cover art signals rebirth, though before he can shape the narrative he appears to have been struck down with a dose of nihilism, becoming bereft of the energy needed to join the dots. Numan is suddenly weighed down by the futility of it all on tracks like ‘My Dying Machine’ where – giving himself the opportunity to speak truth to power – he asks, despairingly: “Why give orders? And why make speeches? Give me a reason to die.” On ‘This Is New Love’ – a title which suggests we might be in for something more upbeat – he sounds positively desolate: “Cold fascination / With dead sound / Oh God let me sleep”.

Numan is just one voice in a gallery full of them, whether it’s Niles’ icy soprano, Rrussell Bell’s overdriven and often overblown guitars, Pat Kyle’s oleaginous sax breaks or the jerky samples and spasmodic staccato repetitions of the PPG (“C-c-c-c-come” on the title track comes three years ahead of George Michael’s ‘I Want Your Sex’ though they both sound antediluvian now). Numan seems to be approaching the album all at sea, like Bowie on the first side of Low, only he doesn’t have Tony Visconti, Brian Eno, Carlos Alomar or Dennis Davis to fall back on.

Given his lack of confidence, Numan casts himself as a ringleader of distraction, administering a sleight of hand that renders him semi-obscured behind an extravagant puff of smoke. He even allows his old pal Zaine Griff a line on ‘The Secret’, a moment of weird incongruity in contrast to his usual fastidiousness. If the inspiration is his hero Prince nonchalantly bringing in his coterie on ‘1999’, then the overall effect here is more a noisy night bus full of disconnected malcontents who happen to include a moody blue-haired goth pouting and paranoid and white knuckling it all the way to Edmonton Green.

Unfortunately for Numan, Numa Records didn’t pan out quite the way he’d hoped. The label manager overordered Berserker stock (single and album) that nearly nobbled the operation from the very beginning, while the small roster of acts he signed went nowhere. It’d be another fourteen years before he’d see any green shoots of recovery and he was discovering he had very little business sense in the process. It looked like curtains for Numan in 1984, though as we all know, it turned out to be far from the end of the story.

“For the first time ever, I began to wonder if my career was salvageable,” he wrote in (R)evolution. “For the first few years of my career, everything I’d done had worked out beautifully, and I genuinely believed I had a natural instinct for decision making. I trusted it completely. But as things started to go wrong, it took me far too long to grasp the fact that I had very little instinct at all – I’d just been incredibly lucky.”