In the latter decades of the 19th century, the silk trade in the part of the Ottoman Empire that is modern day Lebanon collapsed, as European markets took advantage of the era’s technological advances in transportation to purchase cheaper Chinese goods instead. It prompted a mass exodus of perhaps as much as half of the area’s population, a third of whom would settle in Brazil.

Just why so many emigrants landed there in particular is debated. Popular belief puts it down to two visits by the well-liked Brazilian emperor Dom Pedro II to the Middle East in the 1870s, where he is said to have implored the peasants he met there to seek a better life in South America. Eliane Fersan, a researcher on the history of Lebanese migration, put it less romantically to Executive Magazine in 2014 however, arguing that many were refused entry into the United States, and so travelled southwards rather than returning all the way home.

Not tied to prior agreements to become farmhands, as had been arranged for European emigres, in Brazil many expats became travelling peddlers, or ‘mascates’, spreading out across the country. Though tough work, their money went to themselves rather than agrarian landlords, and within a few generations they were able to rise higher up the country’s social ladder than other immigrant communities. “An illiterate emigrant goes to America and after six months sends back a check for 300 or 400 dollars, more than a teacher’s salary or two years’ work of a shepherd,” despaired one church leader at the time back in Lebanon as his congregation dwindled, as quoted in Roberto Khatlab’s Lebanese Migrants To Brazil.

Due to the 19th century’s patchy immigration records, it’s unclear how many Brazilians today have Lebanese ancestry, but estimates range between 3 and 6 percent of the country’s more than 200 million people – a number perhaps larger than the population of Lebanon itself today. More telling than that is that at least ten per cent of the country’s parliamentarians now claim that heritage, which speaks to the level to which Lebanese and Brazilian societies have now integrated. There were remigrations back the other way too, particularly when the Lebanese state (initially under French control) replaced Ottoman rule in the years after the First World War; today there are approximately 20,000 Lebanese-Brazilians (referred to as ‘Brasilibanês’) in Lebanon.

In the mid-20th century, until the outbreak of civil war in 1975, Beirut was enjoying its ‘golden age’ of cosmopolitanism, becoming a melting pot of global cultures. Hotel clubs became central venues for the thriving music scene that came along with it, and for conversations between musicians of various backgrounds playing in their house bands. Back in Brazil around the same time, bossa nova was growing rapidly from its roots in Rio De Janeiro into a worldwide craze, and naturally given the links between the two countries, Brazilian bands would always include a Lebanese date at the end of their European tours.

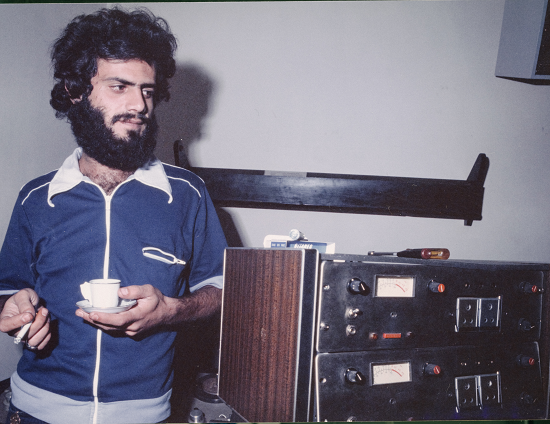

All the spirit and energy of that time is distilled in microcosm on the latest reissue from the label Habibi Funk, an album called Oghneya by the band Ferkat Al Ard. Originally released as the band’s debut in 1978, it is more than just a mashup of Arabic and Brazilian music – melodies and rhythms from each duck and weave around each other like butterflies. It all stems from a meeting in 1974 between one young Lebanese musician, Issam Hajali, and a trio of Brazilians who were playing in a number of bands across the city, Alex, Pelé, and Rose. Alex, a guitarist, would have a profound influence on Hajali, who told Gabrielle Messeder in her essential essay on Lebanese-Brazilian music Brazilian Encounters: Beirut’s “Golden Age,” Ziad Rahbani and Lebanese Bossa Nova: “The first time I looked to his fingers, it was, unusual positions, you know? I won’t forget in my life. [laughing] The G, it’s not a G, it’s G with […] fucked up with something!” It would have a huge impact on his own playing.

Civil war broke out in Lebanon a year later, and Hajali fled for a time to France and Cyprus – a radical leftist and political activist, his safety was majorly compromised by the war. In the process he lost touch with the Brazilians, but still carried their influence with him. In fact, the more the once-thriving Beirut music scene was obliterated by war, the more he poured the sounds of the lost golden age into his work – his 1977 album Mouasalat Ila Jacad El Ard, which was released before Ferkat Al Ard was formed and reissued on Habibi Funk in 2019, which was recorded in Paris, notably contains far less of a Brazilian influence than Oghneya which was recorded with bandmates Toufic Farroukh and Elie Saba upon his return to Lebanon; the second record’s increased cosmopolitan energy is like an act of resistance, intensifying in strength as Hajali moved closer to its former home.

This statement was not made alone. On his return to Lebanon, he befriended Ziad Rahbani, another Beirut musician who had fallen in love with Brazilian music, and who had pioneered the genre ‘Lebanese bossa nova’. Rahbani’s mother Farouz was one of the country’s biggest music stars, and his arrangements of classic bossa nova songs for her to sing would be a major factor in the genre’s enduring popularity across the country. It’s thanks to Rahbani’s arrangement efforts on Oghneya that the record moves with quite so much elegance.

Still popular in Lebanon today and well-known for his own enduring and outspoken leftist views, Rahbani was a good fit for Ferkat Al Ard, whose left wing politics were uncompromising – Hajali claims he refused to even step foot in the Beirut Holiday Inn because of its ties to American capitalism, despite its status as one of the centres of the music scene – and they are woven through Oghneya in more ways than one. The lyrics are adapted from work by the Palestinian poets Samih al-Qasim, Tawfiq Ziad and Mahmoud Darwish, a deliberate statement given the alliance between leftists, Muslims and pan-Arabist Lebanese groups with the country’s significant Palestinian population during the war. The way in which it was originally released – self recorded to individual cassettes, on which the band would cut down the tape by hand in order to fit their running time – is also testament to the depth of the band’s desire for their music to be heard no matter what the barriers.

For all of this, it is important not to oversimplify. As Messeder points out, “exoticist and racially fetishistic attitudes towards Brazilian musicians were—and are—commonplace, revealing […] fissures in idealized imaginings of the cosmopolitan conviviality of the ‘Golden Age,’” and there is an irony to the fact that in Brazil bossa nova was associated with the capitalist elite, rather than leftist rebellion. In addition, the Habibi Funk reissue does not contain Oghneya in its original form; after tracking down Hajali to the shop he now runs in Beirut, the label were informed that for personal reasons among the band’s former members, original album tracks ‘Ghfyara Ghaza’ and ‘Huloul’ would have to be replaced by the song ‘Juma’a 6 Hziran’ as a precondition for the rerelease. Yet this does not dull the power that Oghneya still contains today, music that stands on the foundations set by generations of two-way emigration where it crackles with the joy of cultural exchange, blazes with the intensity of resistance, and marks a powerful tribute to what was lost.