The axiom of Cream’s unfaltering brilliance was so pervasive in the late 60s that even the Beatles fell for it. “You need Eric Clapton,” guitarist George Harrison told his bandmates at Twickenham Film Studios on 10 January 1969, before he fleetingly quit the band and sulked off for five days. John Lennon and Paul McCartney sought to reassure their guitarist at that moment, all captured on camera and recently aired in Peter Jackson’s Get Back documentary: “No, you need George Harrison,” countered Lennon.

Harrison’s absence did start machinations however, and replacing one of the Fab Four with the man who’d soloed all over ‘While My Guitar Gently Weeps’ was briefly mooted. It’s little wonder, given the reputation Cream had forged for themselves in the three years they were together, before their farewell gigs at the Albert Hall in November ‘68. Cream were the first “supergroup”, a neologism coined by Rolling Stone’s Jann Wenner in 1966, with all of the Nietzschean idealism and the archetypal masculinity associated with that word fully intended.

Drummer Ginger Baker, especially, was never one to shy away from expounding upon the group’s brilliance, or his own for that matter. There was nothing ironic about the name Cream. They believed they were the cream of the crop. Baker also firmly held that their contemporaries were technically inferior to the trio of players in his band. With such unshakable self-belief and with the music press doing their bidding, it’s hardly a surprise that a kind of mass folie à plusieurs broke out and record buyers became convinced they were dealing not with mere musicians but übermenschen. It was a confidence trick akin to the Raj.

Two years later, Baker took his physeptone-powered road trip from North to West Africa via the Sahara desert in a Range Rover, complete with a cameraman recording various travails with local police. By then, his mythical status had only grown. To be clear, Clapton and Baker were not bad players, rather their reputations preceded them and their stock was built on years of overinflation. Only now, when people have started again to question Clapton’s character thanks to his dubious outpourings are the delusions beginning to clear. “Slowhand” was quite average compared to the best of the best, while his songwriting — once you strip away contributions from co-writers and notice the prevalence of covers — is a story of mediocrity and chicanery. Baker, the powerhouse of psychedelic rock, has never been held up to such scrutiny, but his style is left wanting when it comes to Afrobeat, as we’ll see.

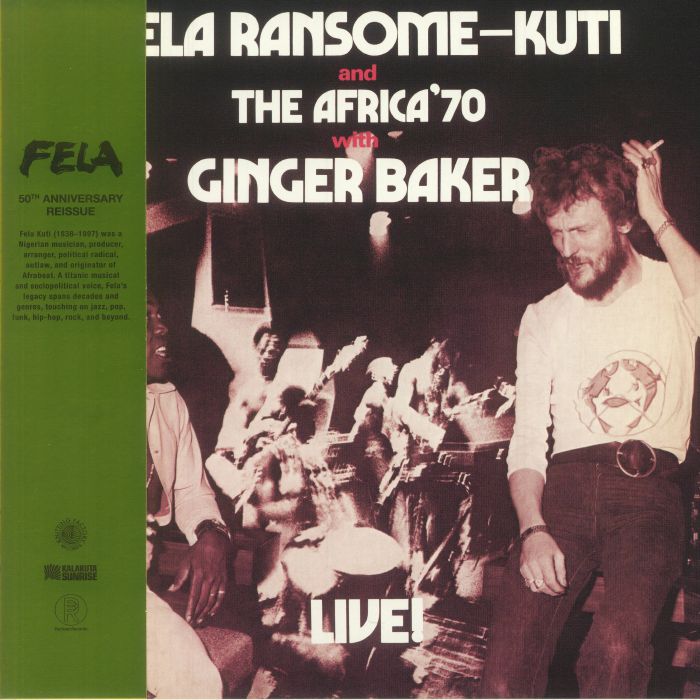

For the 50th anniversary of Live! by Fela Ransome—Kuti And The Africa ’70 With Ginger Baker, recorded at Abbey Road with 150 people crammed into a large studio to give it its live feel, Fela’s estate has decided to reissue the 2014 edition all pressed up on red vinyl, with an additional disc featuring two Baker and Tony Allen drum duels recorded at the Berlin Jazz Festival in 1978. If interminable 15 minute drum solos are your jam, and the one on ‘Ye Ye De Smell’ isn’t long enough for you, then this version is a must.

Ginger Baker and Fela Kuti actually went as far back as 1960, when the latter was studying at Trinity College by day and performing highlife jazz at the Flamingo Club with Remi Kabaka on drums. Ten years later, Kabaka was playing with Ginger Baker’s Air Force, at least until he was seized by immigration officials at a French airport and then deported after they noticed his three month British-issued visa had expired. Baker had the bright idea of sending a telegram to both Fela and Remi in Nigeria as he made his way through the continent. Once reunited, Fela’s record company suggested the live recording, and they would also collaborate on the Baker’s 1972 Stratavarious solo album, which has its moments including a cover of Air Force’s ‘Aiko Biaye’, but any further musical involvement was curtailed thanks to a bizarre drugs bust.

Fela Kuti, in need of funds to transport his band to and around England for a UK tour, sent one “Mr Lewis” over from his Kalakuta Republic compound in order to make some money in advance. Arriving in Heathrow with only a large drum and Ginger Baker’s home address and telephone number on his person, customs officials were unsurprisingly suspicious of Mr Lewis. They were right to be too: the drum contained 35 pounds of potent Nigerian grass. The tour was cancelled, Ginger Baker’s house was raided, and any further integration into Africa ‘70 was brought abruptly to a halt. The plan had been for Baker to accompany Africa ‘70 on their UK tour as well as a BBC session, and his fame and prestige would have no doubt shone the spotlight on Fela Kuti and probably helped bring him into the British mainstream, a fact Baker didn’t shy away from in his congenitally boastful 2009 book Hellraiser: The Autobiography of The World’s Greatest Drummer.

In the same year Baker met Fela in 1960, he was also introduced to the Watusi drummers by the seasoned jazz sticksman Phil Seaman, who played him a field recording of East African percussionists on vinyl. Having, by his own admission, “snorted a jack” just before listening, Baker had an epiphany: “I joined in and for the first time I felt the pulse of Africa”. He walked home to his wife Liz in the morning “going over 12/8 rhythms to the 4/4 of my footsteps… Africa was in my blood and I couldn’t wait to play my drums.”

Baker became transfixed with Africa, and set up his own studio in Lagos called Batakota in 1973. It’s important though to state that Africa is a large continent, and Nigeria and Burundi are nearly two and a half thousand miles apart. The Burundi beat has nothing to do with Afrobeat, which draws on highlife jazz and the unmistakable funk grooves of players like Clyde Stubblefield, James Brown’s most celebrated beat-keeper. Baker came from a different jazz tradition to highlife, and his emphasis on the one beat made him an unusual drummer in rock and roll at the time he made a name for himself (listen to the stresses on ‘Sunshine Of Your Love’ and notice how they’re out of step with the standard 4/4 rock beat of the time). Baker might have been a paradiddling monster, but he clearly couldn’t adapt in the same way Tony Allen could.

When I interviewed Allen for Huck a few months before his death in 2020, he spoke warmly of his friend, who he’d last seen join him for a show despite the fact he wasn’t well: “I saw him backstage and I said, ‘What the fuck are you doing here?’ He was sick. He told me he’d just been discharged from the hospital. He didn’t look good. I said, ‘You should have stayed at home’ but that’s a gentleman. He didn’t want to disappoint me.”

Despite their apparent fondness for one another, and the fact Allen once told Rolling Stone that Baker “understands the African beat more than any other Westerner", you suspect Allen would have been relieved that Baker was no longer a part of the setup after the drugs bust, given their inconsistent playing styles. He attempted to break it down for me as to why: “In the first place, he’s using a double bass drum whereas I’m using just the one. He uses the high-hat but it’s closed because his legs are busy with his bass drums. The way drumming sounded to him was the opposite to me. So when we played together, I always made sure there was plenty of space for us so you could hear him and you could hear me too. If we’re both doing the same thing, you would hear nothing. There’s no point in doing the same thing when one person can do it."

Accordingly, ‘Black Man’s Cry’ never really settles into a relaxed groove, partly because Baker was not a relaxed man. Compare the track with, say, the rhythmic elasticity of ‘Expensive Shit’ or ‘Kalakuta Show’, and you feel it dragging ever so slightly, led as it is by a maniacal, undoubtedly gifted, non-Afrobeat playing drummer. The emphasis on ‘Let’s Start’ too comes at the beginning of the bar, with the conga players led by Henry Koffi doing much to finesse the sound and paper over the cracks with polyrhythmic adhesive.

Baker couldn’t be faulted for his curiosity and desire to play African music; furthermore, he set up his studio in Lagos during a particularly turbulent time in Nigeria’s history and he was an ambassador for Afrobeat, but the idea he was a jazz fusion and world music pioneer is generous at best, with a whiff of the white saviour complex at worst. As great as Live! is, it probably would have been even better with Tony Allen leading and not having to fit his playing around someone else. Ginger Baker was a brilliant drummer, and he would have been the first to tell you so, but he wasn’t an Afrobeat drummer. Perhaps someone should have said to Fela Kuti: “No, you need Tony Allen.”