What does cinematic mean in the context of music? Used frequently in music writing, it can just as easily refer to the viscerally paralysing orchestral dissonance of Bernard Herrmann as it can the smooth, elongated synthetic textures of Vangelis or Tangerine Dream. It’s a word that has become shorthand for music that stimulates the imagination and creates pictures in the listener’s mind, though as a descriptor, it lacks any definition as any such images created in the mind’s eye surely rest with the beholder rather than the music itself.

Fantômas’ music is inextricably cinematic, although it may not correlate with the definition most people subscribe to. Conceptually, it could not exist without the cinema, and very specifically, cult cinema. Fantômas make, or made, an unrelenting noise that comes at you from all angles, biting and scratching and screaming, a Cubist representation of celluloid that envelops you and overpowers you. Siouxsie and the Banshees might have sounded very different without German expressionism; or M83, were there no 80s action movies made by John Carpenter or Luc Besson decorated with synthesiser scores, but Fantômas are entirely contingent on the medium.

Mike Patton’s strange supergroup are a silver screen phantasm made flesh, an overstylistic representation of trashy horror, a tangible embodiment of the ‘midnight movie’. It’s not always easy on the ear, but you can’t help but applaud the vision. Fantômas’ music is made with such attention to detail, with so many disparate tendrils captured and harnessed together, that you begin to understand why Patton spent the last 30 years refusing to talk about Faith No More in interviews. Admittedly, it was the band that brought him to the wider attention of the world, but he arrived as a replacement for Chuck Mosley, who had broken most of the ground already.

Faith No More were, and sometimes are, a great rock band, whereas Fantômas invented their own musical language with a virtuosic intensity that pushed performance into a sphere we’ve not entirely caught up with yet. The idea of ‘world building’ in music writing is as common as the use of the descriptor ‘cinematic’, and yet Fantômas more than almost anyone created a hermetically-sealed world that is like nothing else. Such is the density of most Fantômas tracks that no videos were ever commissioned – which seems ironic given the medium the whole project is focused on. “I think the music is complicated enough,” Patton told The Wire in 2005. “There’s enough information in there – you wouldn’t need any more stimuli with this music, in my opinion. It’s already borderline overkill.”

Furthermore, FNM is the de facto band of the founding bassist Billy Gould; Fantômas was hitherto the clearest transcription of the music in Patton’s head, made from “comical” demos he’d painstakingly assembled with every note replicated by musical delegates in the shape of the highly capable Slayer drummer Dave Lombardo, Melvins guitarist Buzz Osborne and Mr. Bungle bassist Trevor Dunn. If that all sounds like control freakery then you can perhaps understand how annoying it might be if all the journalist from Rolling Stone wants to know is when Jim Martin is going to return from the pumpkin farm.

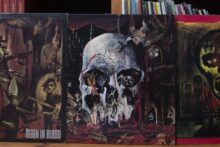

With 1999’s self-titled debut, Patton and his acolytes took death metal and the avant garde – two of the most alienating genres known to man – and brought them together in one pernicious package. There are interjections too of loungecore and exotica, spasmodic and fleeting, all presented through the prism of pulpy noir cinema and b-movie aesthetics. In hindsight, Fantômas self-titled 1999 debut feels a little overly self-conscious in its aims, as the deliberately gaudy cinema poster spoof on the album cover attests. The bald protagonist on the face is presumably a nod to the 1964 film version of Fantômas, itself derived from the original French pulp crime novels by Marcel Allain et Pierre Souveste, some fifty years earlier; in this iteration the figure resembles Thunderbirds’ arch-villain The Hood.

Fantômas sets out its stall with tracks represented as the pages of a comic book: ‘Page 12’ hints at a tune between the nightmare scream and the clearing of a throat, while ‘Page 13’ is a one-and-a-half second clip with nothing on it save for a snippet of cymbal residue from the previous track. It certainly works in its execution as a whole; the players, more than on any other Patton project, learned by rote the brushstrokes he was aiming to splurge across the canvas. That uptight supercharged intensity seems to diffuse slightly for the next album The Director’s Cut from 2001, and it’s while moving around in the skin of Hollywood’s great composers that Fantômas become fully reanimated.

The Director’s Cut is not so much a covers album as a nightmarish Dadaist tapestry where their own agenda interrupts hallowed compositions and, in many cases, shreds them to bits. Nino Rota would no doubt have been perturbed by the foreign object growing within his The Godfather composition, a musical interloper that eventually devours it without even the courtesy of leaving a horse’s head between the sheets. The Omen’s ‘Ave Satani’, meanwhile, ups the creepiness and the camp when thrashed out by Lombardo in double pedal excelsis, somehow making the National Philharmonic Orchestra sound flat.

Other tracks play it straighter: Henry Mancini’s main title song for Charade is lovingly reconstructed with the same Latin percussion and twanging guitar, while Herrmann’s Cape Fear is oddly reminiscent of Faith No More’s Black Sabbath impression on ‘War Pigs’. For the theme from Rosemary’s Baby, Patton drops in a knowing nod to Goblin’s classic Suspiria soundtrack by singing the wordless tune as breathily and as jejunely as he can muster, bringing added menace, were it needed. The Director’s Cut works so well because of how meticulously its put together by an ardent cinephile who cares about getting it right, though there’s also a sense that the musicians have more space to roam or, if not, are very much in the Fantômas groove where the debut feels more like a learning curve.

By 2003, the band had found its working groove, keeping up with Patton’s prolificity, managing to sire two albums out of one set of sessions. First up came Delìrium Còrdia (released in 2004), curiously missing from this current batch of Ipecac reissues. The label was not forthcoming in its reasons for not putting out what could be regarded as the most difficult record of the four, even with some stiff competition, though the fact its one hour 14 minutes of musique concrète, oblique musical interludes, background hiss and sporadic interjections of percussion are supposed to be listened to in one sitting appears to be reason enough; there are windows of opportunity where the sound drops out completely that could have precipitated a quick flip of the disc on the turntable, though perhaps that’s not in the spirit of the original’s objective.

Delìrium Còrdia clearly doesn’t lend itself well to the vinyl format – nevertheless, I was surprised to discover how much more palatable and less far out it sounds now than when I first heard it 20 years ago. I interviewed Patton at the time, apologising for having only had the time to listen to it once. “Once is enough,” he replied with a laugh. Like Apocalypse Now, it only needs to be revisited generationally and, let’s be honest, would be the least likely to have its singular groove retired from too much wear.

Last but not least comes Suspended Animation – recorded in 2003 and released two years later – which splices thrash metal with Looney Tunes samples and chopped up anime in what feels like the logical conclusion to the Fantômas project itself. That has proven to be the case thus far. The tracklisting this time takes in the 30 days of April and celebrates international days from around the world: track 12 is dedicated to Cosmonauts Day in Russia, track 15 honours That Sucks Day in the US, and track 23 nods to Turkey’s Çocuk Bayrami. If thematically that doesn’t entirely work, the wackiness seems appropriate when applied to the indomitable and sometimes irritating delivery, such is its piledriving alacrity. The only let up comes with the conclusion, where things take a darker turn and Bugs Bunny breaks the fourth wall: “Well, what did you expect in an opera? A happy ending?”

Rumours and aspirations concerning a new Faith No More album will surely persist as long as the key players are with us; 2015’s Sol Invictus only staved off demand for so long. Could there be more call for a new Fantômas? Certainly the nature of the way we use screens has transformed in the last 20 years, meaning what felt like a wrap with Suspended Animation might not be the end of the story. There’s certainly plenty of potential to mine there, but for now, that’s all folks.

Fantômas, Director’s Cut and Suspended Animation are reissued today by Ipecac