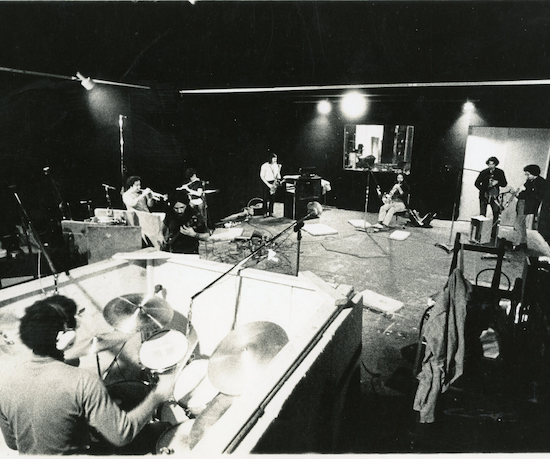

Dickie Landry group recording Solos with Leo Castelli, courtesy of Unseen Worlds

The New York of the 1960s and 70s is the exception to the rule that mythologised periods of the past are generally not worthy of the effusive narratives that describe them. From the Downtown music scene and avant-garde jazz to pioneering visuals and performance art, Gotham’s social and cultural circumstances had coalesced into an innovative scene that could unleash experimental creativity. It was a period of redefining what art was and could be. The lines between media blurred and formal constraints were thrown out the window. In particular, contemporary Western art – both music and visual – owes a great deal of gratitude to this era that saw Fluxus, Tony Conrad, Joan Jonas, LaMonte Young, Eva Hesse, and countless other collectives and artists pave the way towards new forms. Hooked on exchanging ever more challenging concepts, these heads gravitated towards communal spaces – lofts that transformed into studios, performance venues, and above all meeting spots. And in one of these lofts lived Richard ‘Dickie’ Landry.

Having moved to New York from his native Louisiana in 1969, the saxophonist, composer, and visual artist quickly became a prominent figure in New York. Influenced by a circle of friends that included Gordon Matta-Clark and Richard Serra, he found himself immersed in a world of avant-garde artistic ideas, eager to borrow and channel them into his own music. Simultaneously, he took up photography, ingraining himself even deeper and turning a side job into an important feat of documenting artworks and evidencing the then bustling scene. However, it was the introduction to Philip Glass that proved crucial for his career. Shortly after having met him, Landry became an essential member of the seminal composer’s ensemble, while his loft, located on Chatham Square, inspired the name that they later gave to their record label in 1971. And like that flat, his art became a crossroads of styles and approaches, from lyrical minimalism to fiery jazz.

Landry was a prolific musician, playing concerts as often as he accompanied installations and theatre pieces, but outside his work as band member and sideman – notably for Laurie Anderson – he has scarcely released recorded music. These three new reissues on Unseen Worlds thus join the previously reissued Fifteen Saxophones as artefacts crucial in understanding Landry’s music and artistic impetus. 4 Cuts Placed In "A First Quarter" and Solos were first released in 1973 on Chatham Square Productions, while Having Been Built on Sand was pressed to vinyl in 1978 by the Rüdiger Schöttle gallery in Munich. The albums vary wildly in their concepts and aesthetics, yet share glimpses of a singular vision operating behind the scenes.

Epitomising Landry’s immersion in arts other than music, 4 Cuts Placed In "A First Quarter" documents several pieces that he contributed as a soundtrack for conceptual artist Lawrence Weiner’s experimental film A First Quarter. Inspired by the French New Wave, the feature-length film feels like a subversion of that movement. Its scenes appear out of order and on top of each other, reconstructing a new reality as much as investigating our own. The film is almost archetypal for Weiner, if there even is such a cornerstone in his diverse oeuvre, in that it explores the simultaneous tactility and fluidity of language, picture, and sound, while the script is based on Weiner’s existing writings delivered with stunning aloofness.

Dickie Landry group recording ‘Requiem for Some, from 4 Cuts Placed in "A First Quarter", courtesy of Unseen Worlds

Landry’s soundtrack, made from pieces he already had in hand when asked to create something for the film, is the opposite: lyrical, warm, and often pensive. ‘Requiem For Some’ is all about sustained tones that Robert Prado on trumpet, Richard Peck and Landry himself on saxophones, turn into shimmering textures and let flow over David Lee and Rusty Gilder’s propulsive but understated rhythm section. The latter creates a repeating, circular structure rather than moving the piece forward. The next two tracks, ‘4th Register’ and ‘Piece For So’, are solo showcases for Landry on tenor saxophone and Gilder on double bass, each of them following reverberant, often lusciously melodic lines, while ‘Vivace Duo’ sees Landry and Peck duel off into wild free jazz.

While Weiner and Landry would continue working together through the years, 1978’s Having Been Built On Sand is their only other recorded piece of music. Divided into eight cuts, the album was captured live with a minimal setup using hanging microphones at Robert Rauschenberg’s studio in Lower Manhattan. As on A First Quarter, Weiner is fascinated by the malleability of language. Using a simple script woven around the phrase “having been built on sand with another base (basis) in fact”, performance artist (and Landry’s partner) Tina Girouard, photographer Britta Le Va, and Weiner read the script while moving around the space, shifting languages, inflections, and cadences, almost as if sculpting letters and words in the air, then tracing their silhouettes. In some spots, their delivery is resolutely flat and monotone. In others, it resembles an impassioned argument, bursting energy in short exchanges. The words, meanwhile, remain the same. Landry moves between them, letting out timid yelps, whimsical chords, and long, yearning licks from his saxophone. “Then, is use a meaning or a meaning a use”, Weiner shouts and laughs snorting, while Landry circles around him, questioning, probing, and screaming like a snake-charmer.

Both Having Been Built On Sand and 4 Cuts Placed In "A First Quarter" more than stand on their own as purely music releases, devoid of context. However, neither is quite as exhilarating as Landry’s 1973 release Solos. The album is an almost two-hour-long collection of excerpts from an even longer performance that Landry and a cast of collaborators similar to the one featured on 4 Cuts – most of them from Louisiana and at one point or another members of Glass’ orchestra – performed at the Castelli Gallery in February 1972. A sense of spontaneity dominates over this record, from the events leading to its organisation and the ad hoc way it was recorded by sound engineer Kurt Munkacsi to the music itself, brimming with the fire of free jazz and free improvisation.

The eight long passages presented here find themselves in sonic territories somewhere between the grooving, funky electric jazz of Miles Davis’s Bitches Brew and the intense music Ornette Coleman, Albert Ayler, John Coltrane, and Peter Brötzmann were making around that time. Propelled forward by Lee’s relentless syncopated drumming, the ensemble blazes forward with nary a pause. Alan Braufman, Jon Smith, and Richard Peck’s reeds scronk and blare in excitement, while Rusty Gilder and Robert Prado’s upright and electric basses burrow away trembling low frequencies, chasing behind them. Landry switches between electric piano and saxophone here, adding another layer of textural mischief to the chaotic but controlled collective improvisation. There are moments of enticing soloing and almost soulful duo interplay across the cuts, but nothing comes close to the excitement of a band in full free jazz swing.

Taken as a collection, these three releases are worth owning on merit of their historical value and as a primer to an oft overlooked but important artist. But above all else, the music included on them still feels very much alive, immersive, and relevant. If you let it, it might even be transportive – transforming whichever space surrounds you into an energetic 1970s New York performance venue or a gallery filled with innovative sights and sounds.

The reissued versions of Solos, 4 Cuts Placed In "A First Quarter" and Having Been Built On Sand are all available now via Unseen Worlds