The Pop Group always seem the band from the post punk era most able to sound like an actual riot. Eschewing the art school abstraction and urban austerity of their contemporaries, their songs sound like cacerolazos. Mangled reggae and funk grooves charge through layers of echo and speaker burn, Mark Stewart’s vocals equal parts fierce rant and absurd theatre. Never sounding chaotic, rather an attempt to conjure a hierarchy-less world through sound, this febrile mess came fully formed on the five piece’s 1979 debut full length, Y. An album which feels like it’s rising from somewhere between a dingy pub backroom and council estate soundsystem to punch uncompromisingly upwards.

Disbanding in 1981, The Pop Group reformed in 2010 for an ATP curated by Simpsons creator Matt Groening. Since then, they’ve released a couple of new studio albums, alongside remasters of Y and second album For How Much Longer Do We Tolerate Mass Murder, as well as live albums, compilations and more.

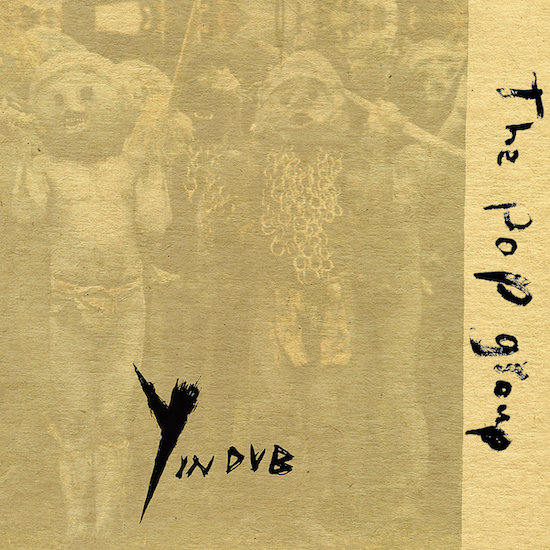

Their debut is now being revisited once again, Y In Dub sees Dennis ‘Blackbeard’ Bovell MBE, the original producer of Y, lay down dub versions of the original’s nine tracks. But it raises the question, do we really need to take up mental (and actual) bandwidth revisiting an album from the late 1970s? I’d venture in this case, yes.

It’d be easy to lament Y In Dub as another symptom of the age of the reissue, the deluge of old albums getting polished and then reprinted. With limited pressing capacity, especially for vinyl, smaller labels and artists can find themselves in limbo as they wait an indeterminate amount of time to get new music released. Leaving aside the separate, essay in-its-own-right worthy question of why we still place physical releases, and records in particular, on a pedestal, the retro obsession detected by Mark Fisher and Simon Reynolds seems to have struck an absurd nadir. [Y In Dub is itself a victim of the delays at pressing plants; the vinyl release has been put back until 2022, Ed]

Though the underground always finds a way – and amazing new music sprouts through – Retromania seems real. It leaves a particularly queasy feeling when attached to punk and post punk, music which claimed to sit in opposition now being flogged by the nostalgia industry. Depending on how you understand it, The Sex Pistols declaration of “no future” seems hilariously misjudged or eerily prescient when punk records from the 1970s are getting repressed in 2021.

Hand in hand with the rise of the nostalgia industry however, there are variations on the theme that there’s no ‘new’ music anymore. As if blinded by a filter which allows only the familiar elements in something to be heard rather than noticing what’s new. Looking for drastic change overlooks the fact that most breakthroughs only appear that way from hindsight. These moments of upheaval are really the culmination of small steps which don’t always end up sticking in the memory. Y In Dub seems to aim at the heart of this impasse, showing that searching for some radically different new thing isn’t the only way forward.

Innovation can be found by looking at the familiar from a new angle, a new perspective or orientation allowing new patterns to emerge. As Y In Dub stretches out and reshapes the original, a bit of the past is folded into the present and vice versa to change how you listen to both.

Bovell refrains from buffing up the old recordings and trying to preserve their youthful fire, instead fucking with the raw materials, opening up the bonnet and rewiring the weirdness underneath. It’s apparent right away – the shard of echo drenched clang and growl that opened the original album on ‘Thief Of Fire’ is still here, but it’s been melted down to a strum and shimmer, the new wobbliness letting different textures emerge in the blur. When the groove kicks in, layers of extra space have been added, so that while the notes of the slurred funk bass line are the same, they hit with a new slickness. The cacophony over the top has been dissected into fragments, so slithers of guitar bounce through effects and the tracks’ horns are afforded new prominence.

‘Snowgirl (Dennis Bovell Dub Version)’ again sees the bass swung into the centre when compared to the original, becoming both lead and groove instrument as the drums are disintegrated and flicked out in trickles and stutters. The piano led collage of the Y version morphing into a dose of psyche-lounge funk. ‘Blood Money’ gets a similar focusing – the 1979 recording’s free form freakout latched onto a Captain Beefheart-esque bass line, the wild sonics becoming even more unhinged over the ominous marching rhythm. These dub versions often smooth out the original, but does that mean it loses some of what made Y so powerful in the first place? The answer is sort of yes, but while Bovell’s treatments here refract or bend that spirit on Y In Dub, he doesn’t drop it.

Back in 2010 I saw The Pop Group play live at London’s Kentish Town Forum, sharing a bill with Sonic Youth and Shellac. While the latter two bands seemed well adjusted to the bigger stage, the members spaced apart and bathed in the lights, facing the audience and performing many of the rituals you’d expect of a band at a venue that size, The Pop Group still looked like they could have been playing on the floor of a dark basement. The members were huddled together, gleefully facing each other in the maelstrom they wrought while Stewart flung himself around the stage. Whereas Sonic Youth and Shellac seemed to tighten up the rough edges of their sound to hit clarity through the big room speakers, Stewart and co. used the added amplification as a vehicle to fling their barbed sonics louder and further. This joyful fury ties them to the UK’s current weird underground of noise rock descendants, the likes of Harrga, Guttersnipe, or GNOD. A raging experimentation which feels pulled from the gutter rather than the academy as commitment to noisy catharsis outweighs the need to present a professional veneer.

In an interview with Sounds’ Peter Silverton around the original launch of Y, The Pop Group’s guitarist Gareth Sager said: “We’re not trying to destroy anything. We don’t really know what we’re trying to do. We’re just questioning everything.” That spirit permeates into the overloaded blast of Y, as though the ramshackle pop mess they concocted channeled a collective “Why?!”

Bovell’s edits here tend to peel back the in-the-red cacophony and let more nuance shine through, the riot collapsing into a conversation where each instrument is allowed to be heard. Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri describe a Multitude as “composed of numerous internal differences that can never be reduced to a unity or a single identity… a multiplicity of all these singular differences.” They contrast it to the masses, which nullifies difference, and the people, which treats everyone as a single identity. This digression into political theory provides a lens to think about Bovell’s deconstruction of these songs. While the original Y rendered to music a relentless critical mass of questioning as frequencies and musical traditions collapsed into a riotous din, Bovell opens up space to allow individual instruments to register with more clarity. The intricacies of the music and the broad field of influences gaining greater traction as new overlaps and references, dissonances and harmonies poke through.

Y In Dub ends up getting right to the heart of dub as an evolving, constantly in flux practice. From its roots in Jamaican producers and DJs editing records for use in dance halls, stretching out sections through loops, or amplifying certain frequencies while dropping out others, the dub version has fired out in countless different directions. No longer limited to reduction, later producers, like Lee Scratch Perry, contrast minimalising certain elements with adding palettes of unpredictable sounds and effects to their tracks. From there, delays and equalisers have been used to compose trippy psychedelic masterpieces, reveal hidden layers through subtraction, or multiply fragments into sprawling webs of sound. Most startling perhaps is how it’s moved from the dance floor to the headphones with artists like Topdown Dialectic, Jay Glass Dubs or Space Afrika taking in elements of dub production in a way that seems as much aimed at stationary contemplation as dance floor exertion.

This mixing of signals can be felt in how Bovell bends ‘We Are Time’, keeping the original’s agitated twang while sprawling out sideways. Stewart’s voice swarms through echo and delay as he wrestles with the line “Don’t let time catch up on you”, drum hits splinter into strange murmurations, and the original’s crescendos seem like they’re stretched out over the song’s entire duration. ‘She Is Beyond Good And Evil’ – originally released as a stand-alone single, is almost doubled in length here. For much of the first three minutes the new version switches from sounding like you’re hearing it leaking through from the room next door, to sounding like you’re having it broadcast from an echo chamber installed in your head. Bovell’s use of the mixing board builds layers upon layers, adding trippy, dripping percussion before ultimately ending up like a jam with negative space itself. In both cases, reduction hits expansion to fundamentally alter how the songs interact with space and time, new shapes erupting from the interrogation of the original recordings.

Dub’s history has always been about finding new life in familiar sounds, and new worlds in old recordings. As Michael E. Veal writes in Dub: Soundscapes And Shattered Songs In Jamaican Reggae, one of the defining things about dub, whether it’s a remix or an original production, is the way it “draws attention to itself as a recording”. With Y In Dub, The Pop Group and Dennis Bovell do the same. Rather than holding their 1979 album as sacred, they treat it as a starting point towards new possibilities, turning Y into a urtext to be cut up, collaged and reassembled.

Interestingly, in the interview with Shilton, Bruce Smith, The Pop Group’s drummer, bemoaned copyright as “another one of those things that keep people separate.” While Y In Dub forms something of a closed circuit, in that it’s the person who originally produced it doing the remixing forty-odd years later, it still points to the possibilities found in not holding original recordings as sacred, but allowing them to develop. Dub’s potential as a practice which gleefully discards preservation as it pursues invention. When ‘She Is Beyond Good And Evil’ was first released the band didn’t copyright it, and the new depths that Bovell gets from these tracks raises the question of what possibilities would lie in giving a bigger range of producers the opportunity to explore Y.

No doubt a lot of rock and pop dinosaurs have been reanimated and paraded around in the last few years. As much as the saturation of reissues of old monoliths from the archive is frustrating, the sheer distance Bovell’s remixes travel on Y In Dub mark it out as something different. Reissues work when they bring attention to something overlooked, or when they cause a reappraisal of what got us where we are. Y In Dub manages the latter, poking a stick at form and context to find what new possibilities can be extracted, and defiantly shouting that nothing is fixed. It proves that delving into the archive doesn’t need to be driven by nostalgia or a taxidermist’s desire to preserve past glories. Toying with the recorded medium itself and taking on dub’s mission to find something new in the familiar, it shows lifting artefacts from the past doesn’t need to be an act of regression.