Few artists managed to capture, or market, the American Dream like Norman Rockwell. While he never attained, nor sought, the cool of his more abstract or edgier contemporaries, Rockwell was at the forefront of American iconography, the stories the nation told itself (and the world) about itself, and the faith that it required to believe in it, sometimes against overwhelming evidence to the contrary. As liberal as he was, illustrating Roosevelt’s Four Freedoms or painting The Problem We All Live With, there is a bipartisan quality to Rockwell. He wanted America, at a time of great turbulence, to hold together. He wanted a deeply flawed nation to be the best it could be, to meet the standards it claimed it represented. Despite having a fireside folksiness and an eye for the little profound things in life, Rockwell never escaped the allure of the utopian.

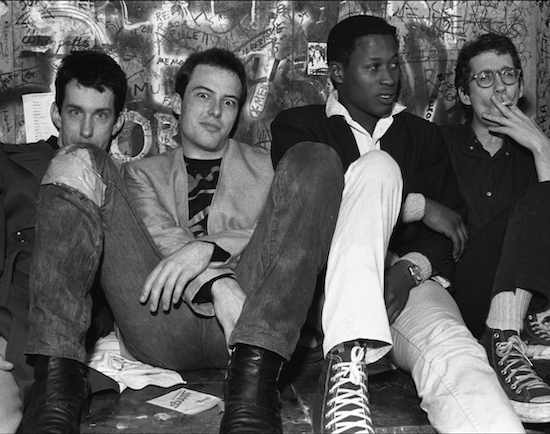

For every icon-maker, there is an iconoclast. For every Rockwell, an anti-Rockwell. In the late 70s and early 80s, Dead Kennedys were it. One photograph of them, looking nerdy and gormless, with sprayed dollar signs on their shirts, presents them best – puckish imps spawned by the American Nightmare. Their name alone characterised them as provocateurs, straying into territory that was crass and insensitive, which was precisely the point. Led by Jello Biafra, they were disgust embodied, golems or gremlins willed into being by the hypocrisies of the greatest nation on earth. They were the children of Reagan, Falwell, Kissinger, Jim Jones. A living personification of a diatribe by an earlier American iconoclast, Henry Miller,:“This is a prolonged insult, a gob of spit in the face of Art, a kick in the pants to God, Man, Destiny, Time, Love, Beauty… what you will. I am going to sing for you, a little off key perhaps, but I will sing.”

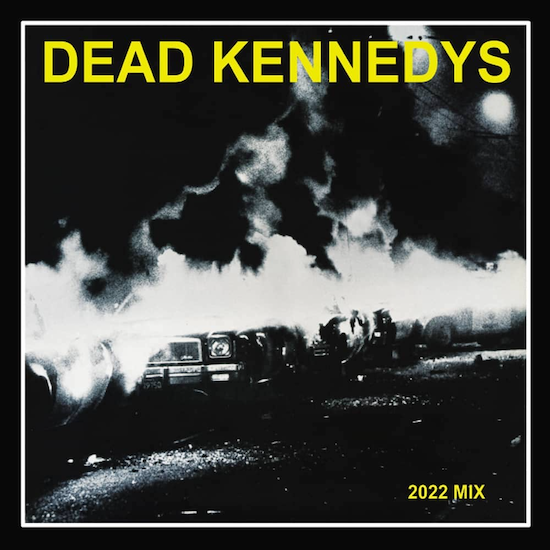

Fresh Fruit for Rotting Vegetables is where Dead Kennedys sang best, a little off key perhaps, but still powerfully decades later. It is an album that remains apposite on a new reissue from Cherry Red, helped by a crisp, clear and vigorous in-the-room remix by Chris Lord-Alge, and yet is utterly of its time, mainly because its time has not yet passed. So much of what it rants about is with us still. Maybe we’re even deeper in the mire. It is a testament to Dead Kennedys, and a condemnation of contemporary politics, that it still speaks to us. It shouldn’t still work but it does, God help us all.

The fact that it has aged well is a surprise. The band were quintessentially juvenile, with a logo designed to be copied onto school folders or carved into desks. Even their names are cartoonish: Jello Biafra, Klaus Fluoride, East Bay Ray, Ted. Combining the erudite and the puerile, the band (especially Biafra) were a cross between Noam Chomsky and the kid from Mad Magazine, a band who could revel in the sound of vomiting on ‘Too Drunk To Fuck’ and follow it with a denunciation of the military industrial complex. It took a lot of smarts to look that stupid, which naturally appealed to a teenage audience. The fact that it still resounds suggests that truths stay true, however gawdy or immature they might seem.

Where Dead Kennedys excelled was in the unlikely role of collectors. For all punk’s puritan qualities – the no past/no future fundamentalist streak – Dead Kennedys’ stripped-down music was balanced with cultural curiosity. The lyric poster that came with Fresh Fruit… was like a Dadaist deconstruction of Americana (Uncle Sam, Buddy Holly, Grease) – an iconoclast’s Sgt Pepper. Dead Kennedys pointed in a hundred directions. Often, it was to satirise, disturb or incite – the controversially explicit HR Giger art for Frankenchrist, the ridiculous image of Shriners in their tiny cars, the tortured dystopian face on Give Me Convenience Or Give Me Death torn from a 1950s advertisement. Yet you get the sense they were revelling, at least partly, in a Rabelaisian way, where they were part of the carnival, rather than with pious disdain. The absurdism was purposeful and iconoclastic; in the same way German Dadaists had in their collages (much mimicked by punk groups in their flyers and posters) mocked the sacred frauds of inter-war politics. The eye was turned this time upon what was holy and unholy in the U.S. If Norman Rockwell was a masterful assembler of American iconography, so too were the Dead Kennedys, even if the things they found were monstrous.

The album begins with a riot and descends from there. The destruction on the cover was from the White Night riots when San Francisco burned, following outrage, especially from the gay community, at the relative leniency shown to the former City Supervisor Dan White after he’d climbed into City Hall and proceeded to murder Mayor George Moscone and Supervisor Harvey Milk, a gay rights pioneer. Biafra would make a bid for office himself, under the slogan ‘There’s always room for Jello’, after he was told, “Biafra, you have such a big mouth that you should run for Mayor”. He came third.

So, what was the first item on the agenda of this would-be future politician? Nothing less than ‘Kill The Poor’. The opening track of Fresh Fruit… is Dead Kennedys’ version of Jonathan Swift’s A Modest Proposal, in which the writer advocated that the starving poverty-stricken Irish sell their children as meat to rich lords and ladies. Taking the same ‘don’t shoot the messenger’ risk as Swift, the message here is also essentially the same; the lives of many already have no value in the eyes of the authorities. Directed at the American Right, time has done something peculiar to this song. While it is certainly not ‘Shipbuilding’ lyrically, Biafra’s satire no longer feels quite as on-the-nose, and it cuts through much of the faux literalism and pearl-clutching purity spirals of contemporary discourse now. Throughout the album, as much as they clearly loathe Republicans, there’s also refreshing willingness to come at elitist liberals from the left, something that has largely and ominously been lost. Musically, they place themselves somewhere between the Sex Pistols (Biafra has a distinct Johnny Rotten-style waver and phrasing), the catchiness of The Ramones, and the louche sleaze of the New York Dolls. There’s even the first hint of the rolling surf rock beat deep in there somewhere.

Written by Carlos ‘6025’ Cadona, who would vanish from the band and public life shortly thereafter, ‘Forward to Death’ is a ragged almost-metal ode to suicidal nihilism, buoyed by the exuberance of its music which thrashes about in multiple directions. There’s a forgivable, even amiable, with the distance of time, delinquent petulance through all of Dead Kennedys’ music and it’s to the fore here. Every time they sound like an adolescent leftover, with all the naivety and cringe that brings, they then leap dramatically back into relevance.

The next song, for instance, ‘When Ya Get Drafted’, feels horribly contemporary considering the Russian invasion of Ukraine. “Are you believing the morning papers? / War is coming back in style”. It’s all there or rather here ¬¬– Cold War paranoia, the sacrifice of sovereign states to brutal geopolitical chess games, Russian imperialism, the ‘Forever War’ of the US, the omnipresent arms industries, nuclear brinkmanship, the media’s acquiescence etc. The music is unmistakably punk, but surf music and rockabilly are never far away in Dead Kennedy land, and the theremin-like sci-fi b-movie solo is proof they are musical collectors as much lyrically and visually.

One of the reason the Dead Kennedys have outlasted some of their contemporaries is that there is a pop sensibility beneath their punk exterior. This was demonstrated by how smoothly Faith No More managed to turn the Dead Kennedy’s ‘Let’s Lynch The Landlord’ into a crooning lounge lizard track. The original version is more visceral, a pogoing pseudo-Marxist advocation of murder. Again, it’s no Crime And Punishment but its tongue is, in fairness, firmly in its cheek. Listening to the lyrics when so little has changed (in fact generational housing access seems to have got much worse) is as depressing as it is invigorating but it is invigorating. Plus, you can see where bands like the Pixies got their strange hybrid surf music side listening to the guitar that cuts beautifully clean through the noise here.

Dead Kennedys circa 1981

Where the album starts to wobble is with ‘Drug Me’, which exemplifies the lamentable tendency, itself prophetic, to pour scorn on working stiffs, a trait that has led to, if you’ll pardon a Jello Biafra-esque moment, the Left’s retreat away from labour, and electability, into… well, so on and so forth. Admittedly, Biafra’s tirade against the opiates and panaceas of the age is as apt as it ever was, more so arguably, with the sinister role of pharmaceutical companies, corporations looming like vultures over every facet of life, and the sirens of the internet. Dead Kennedys were equal opportunity sneerers too so there’s an argument no group should be exempt, with ‘Your Emotions’ continuing the sniping, this time towards conformists. The danger with superiority is that it breeds solipsism, and by extension vulnerability. The hipster, the serf, the mark is always conveniently, and suspiciously, someone else.

The music is another fine example of their magpie eye, being a strange combination of high intensity punk rock, bordering on thrash metal (with the ridiculous polka beat borrowed by both), but also it has this weird 1950s ghost train quality. It’s these ornamental touches, recycled from earlier ages, that allow Dead Kennedys to escape being confined in their own age. They were clearly in the middle of a very distinct scene, but their listening habits were leftfield and somewhere out on the hinterlands. These little twists were hard for copycats to capture or even attempt. They never became entirely formulaic. Few imitators would have the imagination or gall to include a little demented glimpse of the waltz ‘Sobre las olas’ by Juventino Rosas in ‘Chemical Warfare’. The song, a goofy rant about poisoning wealthy golfers and their poolside wives is delivered in mostly unintelligible babble but it does speak of something common to punk rage; a sense of impotence. These are songs about the inability to do things, songs about cages, and yet unlike some of their peers, Dead Kennedys were already going to unexpected places and dropping crumbs along the route.

Side B begins strongly with ‘California Über Alles’. Though it suffers in the manner of gonzo journalism from over-specificity about the politics of its time, its cautionary tale of illiberal liberalism seems apt in an age of ‘Be kind or the police may pay you a visit.’ Musically it’s a portentous wiped-out surfpunk, with Biafra playing the role of the deranged preacher in the chorus (it was the age of televangelism after all). ‘Holiday In Cambodia’ sets its sights on a similar target of crooked and venal elite do-gooders, though the message is confused somewhat, sending them to the killing fields of Kampuchea, other than emphasising how out of touch they are with the brutal realities of the world. It’s an incendiary song though, that still causes a shiver, remembering the horror and morbid fascination of finding that cover, depicting the murder of a Thai student in the 6 October 1976 massacre, in an older cousin’s record collection. Dead Kennedys pointed out paths you might not want to follow but felt compelled to.

One of the ways Dead Kennedys deflate the pomposity that comes with politicised music is that they make you doubt them repeatedly by alternating between the inane and the intelligent. So, you get the straight-out trolling of ‘I Kill Children’ as well as the delinquent ‘Stealing People’s Mail’ and ‘Funland at the Beach’ (“But someone sabotaged the rollercoaster last night…”). It would be overly generous to call them Juvenalian satires, but they contain the odd funny moment of dark mischief and parody. It does feel at times though like Dead Kennedys might be like one of those cellophane fortune-telling fish, perhaps only accidentally coinciding with the truth, until you remember that dumb shit takes up a significant proportion of our lives and why should it not have its place in the musical canon? One moment Dead Kennedys revel in squalor, the next they are its righteous prophets. They combine both in their dash through ‘Viva Las Vegas’, which is both celebratory and condemnatory. ‘Look what this place did to Elvis’ it seems to point out. While we might be tempted to ask what kind of culture produces Dead Kennedys, the real question is what kind of culture needs Dead Kennedys?

Musically, the Dead Kennedys would go on to take the little touches of experimentalism here (the controlled Trout Mask Replica-like chaos of ‘Ill In The Head’, the atmospherics at the beginning of ‘Holiday In Cambodia’ etc) into deeper ventures into surf music, psychedelia and spaghetti western, while always remaining a punk band. In terms of cultural impact, it hard to see what they did, and sacrificed, for free expression in the court cases and controversies to follow as anything less than heroic. You might even start to suspect that they were not that different from Norman Rockwell after all. There may have been something patriotic in what they were doing, according to the definition of a patriot as their nation’s harshest critic. Dead Kennedys deliberate insensitivity hid the fact that they were never remotely as callous as their outraged opponents. Even a song like ‘Holiday In Cambodia’ can be seen as a restoration of perspective, a corrective rather than just disruptive intervention in a world of Nixons and more caring sharing establishment figures.

Maybe Norman Rockwell and Dead Kennedys were seeking answers to the same question, “How to exist in a fucked-up place?” One proposed that you live according to higher standards, the other suggested that you show everyone how fucked up it is. Far from being direct opposites, it could well be, listening to Fresh Fruit for Rotting Vegetables after so much and so little has changed, that the best of Rockwell’s work and Dead Kennedys’ music is where these two points overlap.

Cherry Red’s remastered and remixed version of Fresh Fruit For Rotting Vegetables is out now