It’s hard to overstate the influence that David R. Edwards had, along with Patricia Morgan, as the band Datblygu, on not just Welsh language music but on Welsh language culture, and more broadly on Wales itself.

On Edwards’ death in June 2021 at the age of 56, tributes came from the expected litany of musicians that he’d influenced through his work, but also from the First Minister of Wales, Mark Drakeford, who described his death as Wales losing “a cultural giant”.

Last year, as the Welsh men’s football team reached their first World Cup since 1958, it was impossible to avoid hearing or reading about the adopted second national anthem – Dafydd Iwan’s ‘Yma O Hyd’.

The now legendary song has enjoyed a second life as an anthem of resistance, but when it was originally released in 1983 it was very much in the domain of the Welsh language establishment. As far as Welsh language culture is concerned, the true songs of resistance of this period were coming from Datblygu who had formed the year before.

A figurehead of mainstream Welsh language culture and of the Welsh nationalist movement since the 1960s, Dafydd Iwan’s contribution to Wales and Welsh culture – including stints in jail for his protests – is unquestionable. He is justifiably famous in Welsh-speaking Wales, and since the crossover success of ‘Yma O Hyd’ that status has miraculously converted to the English-speaking side of Wales, too.

However, by the early 80s, the record label he owned, Sain, seemed to release just commercial music in Wales and came to represent a sort of middle-of-the-road, privileged mindset enjoyed by Welsh language middle classes.

A Welsh language TV channel had been secured by direct action and the threat of hunger strikes, and with it came a large number of cushy jobs for a new class of Welsh-speaking media wankers.

The middle class Welsh-speaker’s mindset of being under siege in their own country despite the benefits of a new fledgling media industry, was quite a typical symbol of where things had got to by this point. Welsh-speakers had obtained the levers of control in the media after decades of protest, what chance was there of them dismantling the systems that once oppressed them?

While Welsh-speakers still had chips on our shoulders, a lot of us had become comfortable.

David Edwards on the other hand was a working class Welsh-speaker. As a school leaver in Thatcher’s Britain, he wasn’t in a comfortable position. While he appeared to have found some sort of peace in his later years, he was driven to the end to point out hypocrisy and to draw attention to the things in Wales that he found ludicrous about his own culture until his passing.

“Dave Datblygu”, as he was informally known according to the naming convention of Welsh language bands (akin to saying “Steve Aerosmith” or “Flea Red Hot Chili Peppers”), had a confrontational style with laser-guided lyrics which were hyper-critical of that newly-comfortable class of Welsh-speaker. He was also often critical of the media most bands needed to spread their music, and he was outright hostile towards audiences who he thought didn’t appreciate his band’s work.

The Datblygu track ‘Dafydd Iwan Yn Y Glaw’ (Dafydd Iwan in the rain), on their 1988 album Wyau describes the aforementioned eminent politician and campaigner speaking at an outdoor rally for Plaid Cymru in inclement weather, before simply repeating during the middle eight, “Nineteen thirty-nine”.

A few years later Edwards was ejected from a Dafydd Iwan gig for repeatedly heckling, “Nuremberg 1933!”

Outside of Welsh-speaking Wales, the slaughtering of sacred cows wasn’t a problem for monoglot audiences unaware of the issues covered by Edwards’ lyrics. They recorded five Peel sessions.

“John Peel said that Wyau was the best LP ever released in the Welsh language,” said Edwards, looking back in 2016. “I said, ‘Fucking hell, what the fuck am I doing being a teacher?’ So I moved to Aberystwyth and thought I may as well write another album.”

As an experimental post punk band with an abrasive frontman, Datblygu were frequently compared to The Fall. While it might be an easy shorthand for the uninitiated, in truth that does a disservice to the utterly unique qualities of both bands.

Datblygu and Fall superfan, comedian Elis James said of Edwards’ genius in an interview in 2020 that “He’d hit the nail on the head about things that I’d half had a thought about and hadn’t been able to articulate.”

While the middle-aged Welsh-speaking middle classes were comfortable, the disillusionment of their teenage children with their parents’ generation of music meant that Datblygu would inspire practically everything that followed them in Welsh language music in some way or another.

As a teenager, future Super Furry Animals members Gruff Rhys and Daf Ieuan formed Ffa Coffi Pawb, the name literally meant “Everyone’s coffee beans” but was a homophone of “Fuck off to everyone”; the sort of pun that was typical of David Edwards’ lyrics.

The most obvious tribute to Datblygu’s influence on the Furries was their decision to cover the sincere love song ‘Y Teimlad’ on their Welsh language album Mwng in 2000.

Mwng is the best selling Welsh-language album of all time. It came at the height of the Cool Cymru-era with bands like Stereophonics and the Manics shifting millions of units, Shirley Bassey’s much photographed Welsh dragon dress at the rugby World Cup opening ceremony in Cardiff in 1999, and Cerys Matthews appearing in the tabloids week after week.

In the middle of this fever pitch clamour in the media for Wales and Welshness, SFA released a Welsh album and refused to play any gigs supporting it in Wales. When asked why, Rhys’ response was simple: “We didn’t want our gigs to turn into some sort of Nuremberg rally.”

While Welsh culture was enjoying the tornado created by Datblygu’s wings flapping during the previous decade, Edwards was unable to enjoy the benefits he had laid the foundation for, having been sectioned in 1996.

He was very open about his issues with severe mental illness and drug and alcohol abuse, and despite not receiving the critical acclaim that both Edwards and Morgan were more than worthy of at the height of their productive earlier years, the duo re-emerged with a new EP in 2012.

Their first gig in 20 years came in 2015 at the ‘Cam O’r Tywyllwch’ festival, which was held at the Wales Millennium Centre and organised by Gwenno and Rhys Edwards. The festival was named after a legendary and massively influential 1985 compilation album which featured Yr Anhrefn, Y Cyrff and of course Datblygu.

The audience was a who’s who of Welsh culture keen to pay tribute to, or even catch a first glimpse of, Edwards and Morgan – whose work had created such a major shift for the good in a previously comfortable, stuffy and conservative Welsh language culture.

More gigs and festival appearances would follow, including an invite to All Tomorrow’s Parties from avowed fan Stewart Lee. Two full length albums were released as well, Porwr Trallod and Cwm Gwagle, both worthy of the rest of their catalogue, and perhaps even superior in some ways. They were both shortlisted for the Welsh Music Prize, with Cwm Gwagle missing out to Kelly Lee Owens’ Inner Song.

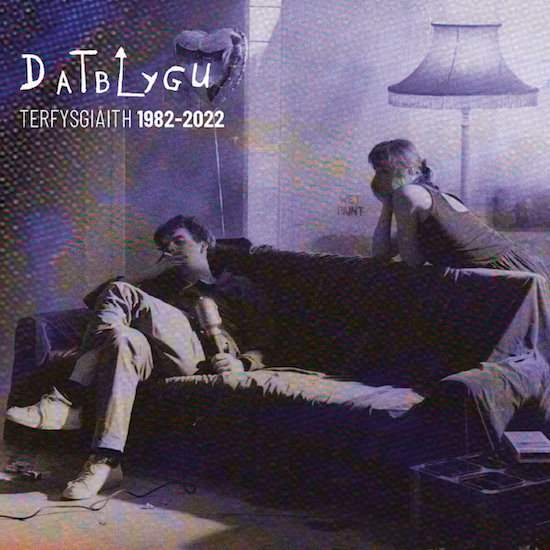

Terfysgiaith 1982-2022 is a two disc compilation of songs selected by Edwards and Morgan, along with a third disc of live tracks, rarities and session recordings. It was to be a celebration of 40 years of the band, however David’s sudden passing means that it now exists as a fitting full stop to an incredible creative partnership that has left a mark on Welsh culture that will be impossible to replicate.

While the days of Cool Cymru are now more than two decades in the past, Datblylgu’s legacy lives on during a new golden age of Welsh language music.

The main distributor of Welsh music is a platform called “Pyst”, named after Datblygu’s second album. Probably the most prolific record label – home to Adwaith and others – is Libertino Records, named after Datblygu’s third album.

Adwaith, a Carmarthen trio who are the only two-time winners of the Welsh Music Prize, have previously found themselves collaborating with Morgan, as well as being championed by Edwards. After a BBC session at Maida Vale in 2017 he sent them a hand-written note: “Congratulations Adwaith for sticking a white-hot metaphorical poker up the arsehole of the London music scene.”

While he was critical of the establishment, Edwards was a vociferous supporter of young Welsh musicians, and was always looking to the future.

The three CD collection includes liner notes from both Morgan and Edwards, along with Emyr Glyn Williams of longtime record label collaborator Ankst – whose 1995 compilation album title S4C Makes Me Want To Smoke Crack shows an allyship of outlook between label and artist that’s rarely seen.

Terfysgiaith includes the final tracks that Edwards and Morgan recorded together, the collection somewhat poignantly freezing in time the catalogue of a band that defied categories, defied expectations, and who were completely timeless and peerless throughout the forty years of their existence.