At the end of the 1980s, the imminent collapse of the USSR was being felt throughout Eastern Europe. In Ukraine, the turn of the decade was marked in the music scene with an increased activity outside the mainstream in the spirit of modern DIY – a movement sometimes called ‘amateur music’. Two centres of independent music emerged – Kyiv and Kharkiv.

While Russian bands were likely to gain wider popularity with the help of major labels, Ukrainian music had no scope for significant backing. With access to duplication equipment limited, they released albums on cassette in limited quantities. Listeners either paid to duplicate these albums in recording studios or copied them from friends. If any music was formally released, it was usually abroad on underground labels in Poland, Germany, and Canada. When compared to today’s methods of release and promotion, everything was upside down – music created as a form of expression, capturing turbulent times in the form of sound, with no thought for how wide an audience it might reach, if any.

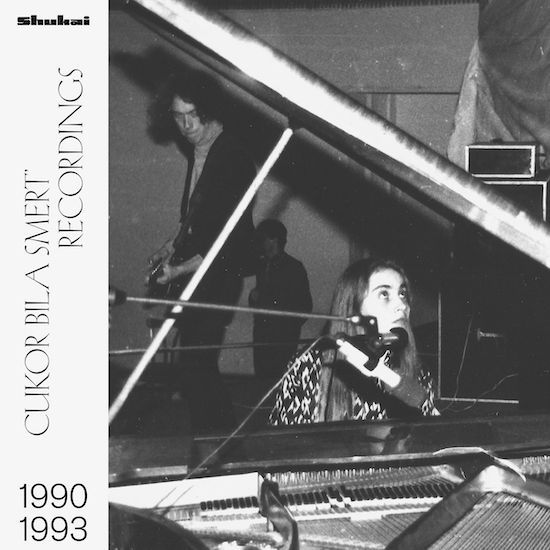

One group, however, Cukor Bila Smert’ (Sugar White Death) bucked the cliches and showed that rock from across the eastern border didn’t need to be synonymous with protest songs. They made their niche, playing on stage with the noise-rock and chamber pop originals of the Kyiv Underground and Kharkiv Novaya Scena movements, which were thriving despite impending decline along with the country’s political fortunes. The band consisted mainly of students from the Glière Music College in Kyiv, interested in the previously banned avant-garde and new wave, standing out from their contemporaries for their use of high female vocals and a performative, gothic instrumental style their country had not previously been acquainted with.

It began as a duet. After graduating with a piano degree, Svitlana Nianio (later known as Svitlana Ohrimenko) began to compose music. Initially playing with cellist Tamila Mazur, she then formed a larger ensemble, joined in 1988 by guitarist Eugene Taran and pianist Alexander Kohanovs’kyi, the latter of whom had previously created original soundtracks for many theatre productions. At Kohanovs’kyi’s house, they would spend their free time playing music, listening, and discussing new ideas.

Kyiv bands of that time were distinguished by their imagination and a sense of humour when they came up with names for their groups. The second half of the 80s had been marked by political instability and the everyday absence of essential food products, prompting Taran’s suggestion of an ironic statement against the country’s yellow press, which, under instructions from above, had suddenly begun to urge the masses to follow a more healthy lifestyle by excluding products that were supposedly harmful from their diet. Amid conditions of total shortage in the late Soviet era, this was particularly amusing. Collaborating with Nianio on their lyrics, Cukor was one of the first bands to write in Ukrainian, and before long began to get rid of any excessive layering, stripping away the cultural references, allusions and reminiscences that were characteristic of the ‘advanced postmodernism’ favoured elsewhere, especially in the wider Kyiv scene.

Photos courtesy of Shukai

In the band’s music, it’s easy to find parallels with Dead Can Dance, Xmal Deutschland, Coil, Swans, or The Birthday Party (I can imagine them playing the role of the club band in Wim Wenders Wings of Desire instead of Nick Cave and co.). Still, it would be wrong to view their work as post punk – they were closer to a kind of depressive baroque, with elements of classical music, simple electronics, synthetic beats, and modestly sketched melodies, all orbiting around the phenomenal voice of Nianio.

Recordings 1990-1993 is a new compilation drawing from the band’s published and unpublished work, curated by Shukai. It opens with the music from their first officially released album, Manirna Muzyka in 1990. In English, the name literally means ‘mannered music’ or can be better translated as ‘primitive music’, which best describes the band’s work. Applying their musical training to restricted instrumentation, they generated minimalist synths and trancelike beats, creating a suspended and dark, somewhat gothic atmosphere. Their music is edgy and theatrical – the dynamics constantly change: at times, the band perform calm and lyrical ballads; at others, they’re harsh and psychedelic. It is pure experimentation with form and structure.

Although each of their songs is short and formally unelaborate on its own, they build a complex mosaic of anxiety, cabaret and darkness when arranged into a more comprehensive whole. Instrumental parts interact with harmonic dissonances, piano swaps with cello and electric guitar, and brass lines mingle with Nianio’s operatic vocals.

The curatorial approach here invites a different perspective on the group’s music. Originally, the lyrical and beautiful ‘The Great Hen-Yuan’ River’ followed the six-part ‘Six Coral Devils’, but here the order is reversed – they begin with a gorgeous melody before plunging deeper and deeper into a world of paranoia and surrealism, from experimental folk, exploding with strings and jagged, unsettling piano phrases, to the shaky, drum-machine-led eccentricity of the final segment. If there could be said to be a single characteristic element of their music, it is the dreamy Casiotone MT-200 keyboard. Its texture, dubbed by Oleksii Dekhtyar – the founder of the band Ivanov Down – as a ‘sugar calypso sound’ was vital not only to Cukor’s creativity but also to the later sound experiments of its individual members.

After the first album was released, Kohanovs’kyi and Mazur left the group. The former started his own project Mr. Kifared and the latter became the bassist of Shake Hi-Fi (which Eugene Taran had co-founded). Now based around the core duo of Nianio and Taran, Cukor would henceforth come together in different constellations to record new material, each of which broadened their ideas. Take, for instance, ‘All Secrets Of A Poem’, which recalls Julia Holter-style minor key synthpop, or the turbulent epic ‘Argolida’, which was the band’s first recording as a duo and is divided into seven parts: from operatic vocals and guitar, we move from synth gargoyles to an edgy children’s rhyme.

On side D of the Shukai reissue, their music is mesmerising and poetic, although more superficial, moving away from their distinctive sound. Most of this section was originally released on the album Selo in 1993, their second and last proper album together. It was recorded with the help of Polish Radio Experimental Studio legend Tadeusz Sudnik in his private Studio of Impossible Sounds. With additional cello provided by session player Boleslav Blazhchyk, the synth speaks of a forgotten past, while Nianio creates vocal meanderings, diving into Broadcast-style, musique concrète impressions, creating an extraordinary sonic rite.

The album’s 90-minute running time shows just how many different forms this band took as each soloist has leaned towards their own sounds, and yet their composition was ultimately a collective effort. There is a stylistic richness hanging over the whole release that is only highlighted by dissonance and contrasting sounds. The band did not agitate politically in their lyrics – affordable electronica abstracts music from its historical and political context. Even though Cukor was creating music during a tumultuous time, they did not attempt to describe that period; perhaps that is why they sound fresh and appealing today.

Perhaps none of this music would have seen the light of day had it not been for a coincidence. Before Manirna Muzyka, the group had in fact recorded two albums – Rhododendrons Coral Aspides in 1988 and Lilies And Amaralises in 1989 – which have been lost. One of a few cassettes of Manirna Muzyka was brought to Vlodek Nakonechnyj by his sister, who was on an internship in Kyiv when she met the musicians. He had started Koka Records in Poland, a label whose aims were to present a variety of Ukrainian artists to the wider world, and it was thanks to them that Cukor Bila Smert’s music could receive a far wider distribution. Koka published their music and invited them to tour, too, but the group couldn’t afford a live show that would convey their sound the way they intended. It would instead remain a studio project.

In 1994, Cukor Bila Smert’ was disbanded. Later, Svitlana Nianio published several solo works, notably with Oleksandr Yurchenko, a reissue of whose work a few years ago was a reminder of her greatness. Other members formed other projects, but they’re remembered mainly via low-quality releases, available only via uploaded recordings on YouTube, which rarely reach more than a few hundred views. Now, thanks to Shukai, we can not only properly rediscover the work of one of the most essential and original groups Ukraine has ever produced, and embrace a unique and ageless sound, a pioneering creativity, that still mesmerises 30 years on.