Cliches become so because they are true, and remain so because they never quite tell the whole story. The music of Jamaica has long railed against ‘mental slavery’ – the idea that just because a colonial power has physically left a dominion, the dichotomies and divisions they have maintained for centuries don’t so easily slip from the minds of those oppressed and ‘educated’ by that colonial power. Look at the servility from certain figureheads of the ‘commonwealth’ around the recent death of Queen Elizabeth II to see the chains of mental slavery still intact. Queen Elizabeth I – who it could be argued first set in motion the British colonisation of Jamaica in the 1500s – gets a mention on ‘Narration’ the second track of drummer Count Ossie’s 1972 album Grounation, a triple-LP masterpiece of Afrocentric Jamaican jazz, funk and reggae thankfully reissued by Soul Jazz on the event of its 50th anniversary. Ossie talks about Queen Bess’ granting of a Royal Charter to slave-trader John Hawkins to start trafficking from East Africa to the West Indies.

A sense of history is crucial to Grounation, but this album remains – particularly in this gratifyingly deluxe new incarnation – thrillingly on the edge of positing a future as well. Its vividness is still down to its collective will to find a new way to be Jamaican, not just recovering lost connections but forging new ones too. It’s vital I think, in any appraisal of Grounation to see it not as some kind of instinctive outpouring of a unified Jamaican culture, but rather to relish it as a record of just what a syncretic, non-coherent space cutting-edge Caribbean culture was at the time, fired by US Black Power and the Black arts movement, as much as dreams and idealisations of a shared African cultural memory.

Because of Ossie’s links with the history of Jamaican music, and because of Rastafarianism’s increasing importance to Jamaican music and politics after independence in 1962, Grounation could be seen as an ‘authentic’ statement of spirituality, an expression of Jamaican ‘soul’, ‘spirit’, ‘roots’ (insert meaningless chimerical term of your own choice). I would argue, however, that Grounation moves us precisely because of its confection, its inauthenticity, its act of imagination applied to colonial and post-colonial history rather than just its pure expression and reflection of the rage and resistance inherent in Jamaican thought at the time. Grounation’s roots are in that most postmodern of faiths – Rastafarianism ¬¬– which from its prophetic birth pangs in the proselytization of Marcus Garvey is a definitively collaged faith – built from a blend of non-Christian pan-African separatist ideals, ancient Gnosticism, 20th century socialist politics and post-modern cultural curiosity. Postmodernity is key to all Jamaican music from the 1950s onwards, including Ossie’s first hit with ‘Oh Carolina’ in 58 with The Folkes Brothers – what you hear on that record is a blend of jazz and blues from Jamaica’s closest culturally-imperialist neighbour – the US – and the Burru/Nyabinghi drums that Count Ossie was passing on to Alpha Boys School pupils in legendary jam sessions up in his Rasta compound in the hills of Wareika, Kingston, sessions in which hymns and popular songs were as likely to be swirled into the mix as traditional Jamaican and African music.

Those Alpha alumni who bought instrumental range & prowess to Ossie’s elemental drum sessions (horn players Roland Alphonso, Cedric Brooks, Rico Rodriguez, Tommy McCook and more) would go on to craft the history of Jamaican music – ska, rocksteady, roots reggae, dub – from the 60s onwards, and by the time Count Ossie summoned both his drummers and Cedric Brooks’ Mystics into the band that was called the Mystic Revelation to record Grounation, Rasta motifs and music had become fully enmeshed in the world of Jamaican contemporary music. DJ Kool Herc remembers a childhood in which Rastas were seen as bad men, outsiders, but that after Haile Selassie’s seminal visit to Jamaica in 1966 (at which Ossie’s Rasta drummers were asked to play) they were seen as avatars of a new anti-colonial, independent Jamaican voice.

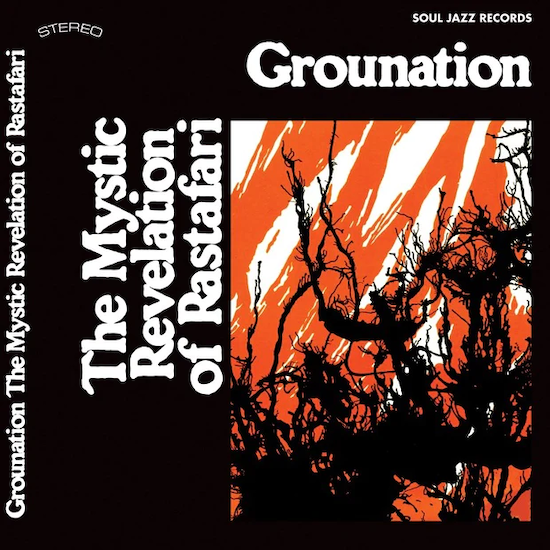

Credit: Soul Jazz Records

Importantly, Rasta ideas in Jamaican music were not an attempt to ‘recover’ African-ness in post-colonial pop, rather they opened up a space whereby all kinds of Black cultural struggles towards overthrowing mental slavery could be incorporated into the mix of Jamaican music, whether that was funk, soul, folk blues or jazz. Crucially, what you hear on Grounation isn’t just music that relays a true history of Jamaica. It’s music that – like contemporaneous music by the likes of Miles Davis, Pharoah Sanders and Fela Kuti – attempts a postmodern blend of the African and the American in a new fusion of the ancient and modern, a new narration of a hidden history, a new prophecy of Black liberation through sound. And throughout it’s an imaginative act, not just an authentic one. What thrills about Grounation isn’t that it sounds as old as the Wareika hills, it’s that yes, it sounds like the studios of Kingston in 1972 but also the jazz clubs of New York City, the funk-jams of New Orleans, even nascent Afrobeat and hi life. And it’s this freedom in sound that makes it mystic in a true time-travelling, teleportational sense.

Originally Jamaica’s first triple album, the album’s first side sets out the stall. ‘Mr Bongo’, a mapping out of the soundscapes to be explored, pulsing stealthy drum patterns, horns adding mournful tones startlingly adjacent to the whole Coleman/Coltrane/Shepp soundworld of US jazz. ‘Narration’ is the story of Jamaica from capture to ‘liberation’, an utterly compelling story told over shuffling minimal beats and bass that then bleeds through into side B’s ‘Narration Continued’. The glorious ‘Mabrat (Passin Thru)’ takes us from Jamaica to a wider Caribbean (almost afro-Cuban) vibe, bossa and samba beats threaded through – always with those Burru drums speaking their own story in polyrhythmic waves eerily preminiscent of dub. It’s at this point, as Cedric’s Anthony Braxton-style wild sax lines explode over the rhythms that you realise the enormous ambition of this record – not just a clarion call to Jamaicans but to a global Black resistance to White power, the side winding up on the gorgeous Sun Ra-style plangency of ‘Poem 1’, a direct statement of music’s power to destroy the lies and deceit inherent in the colonial system, an inversion of Christianity’s promise of afterlife liberation and a firm statement of Rasta’s promises to the present.

The second disc kicks off with ‘400 Years’, a startling reconfiguration of the tune to ‘Scarborough Fair’ with its lyrical muzzle pointed firmly at the British establishment, but also a call to arms for the globally dispossessed wherever they are, whoever has their boot on their necks. ‘Poem 2’ and ‘Song’ are dub poetry before dub exists – a bleak refusal of day’s dawning, a refusal of consciousness in preference for night’s slumber, a suggestion of universal empathy instead of envy and divisiveness. In 1972 Ossie is spelling out exactly the spiritual and political Rastafarianism that would soon infect so much of Jamaican reggae music until the Civil War of the mid 70s – hypnotic tracks like ‘Lumba’, ‘Way Back Home’ and ‘Ethiopian Serenade’ laying down basslines and melodies you will hear echo throughout dub tracks for the remainder of the decade.

The absolute zeniths of this masterpiece are to be found on its title track(s). ‘Grounation’ and ‘Grounation Continued’ are mesmeric steps towards the light of redemption as touched – you sense – by soul and funk as jazz and reggae. The trance-inducing way the grooves build, blend, decay, coalesce is clearly in hock (just as Miles and Fela were at the time) to the temple of James Brown (hence the tracks uncanny adjacency to Can’s music at the time) but there’s something beyond mere ‘influence’ going on here. Rather what you can hear is what you can always hear in Ossie’s music, an attempt to do nothing less than musically spell out the history of a people, explain the present struggles of that people, and suggest ways those people might gain both ultimate connection and liberation from that history.

Such ambition might seem impossible now, in the infinitely entangled crossfire of identities and displacement that is contemporary post-colonialism, but Count Ossie & The Mystic Revelation of Rastafari show it’s achievable with every single moment of this miraculous music. If you don’t know, get to know. If you do know, the extra materials (fascinating sleevenotes, photography reproductions and extra contextualising interviews) serve to make this reissue utterly essential. One of the greatest albums of all time just got better. Do not miss.