“When my parents lived in Ndola, East African families got together and played East African music at Christmas parties. It was a nostalgic exercise, but for us children and teenagers who were forced to dance, we disliked this music.”

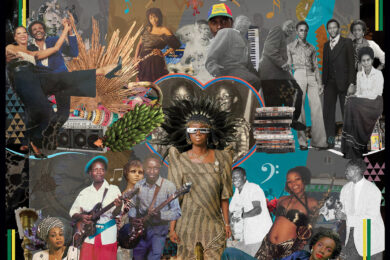

Kampire has changed her tune since growing up in the Zambian town that lends its name to her new compilation, Kampire: A Dancefloor in Ndola. The Kenya-born selector’s first official compilation release spans several eras, locations and canons, but is rooted in the African pop music of the 80s, that so irritated her as a child.

The breadth of styles here is impressive and this is a useful prism through which to view the DJ practice of Kampire herself. Here, though, the context is different. Born to Ugandan parents, and currently based in capital city Kampala, by now Kampire Bahana has arguably become the main pipeline via which Western ears are introduced to the music coming out of Uganda and Zambia than any other contemporary artist from the region. She tends to favour bass-heavy, club-ready tracks, whether that’s gqom, genge, or the kind of bold Afro-futurism Uganda’s Nyege Nyege – her allies – are renowned for.

She became embedded with them around 2014, when she was asked to help with the first edition of their namesake festival; then four years later her breakout Boiler Room set from the same event almost broke the dance music internet, catapulting her onto the global one-to-watch list. Since then, a Residency slot on BBC Radio 1, 2021’s acclaimed No Visa mix, monthly NTS Radio shows and countless international bookings have only elevated that status, capturing the attention of millions via deft mixing and exquisite taste. In comparison to all of this breakneck modernity, Kampire: A Dancefloor In Ndola is an entirely reflective exercise. Running through 12 tracks and a dizzying array of sub-genres, it swerves the 21st Century in favour of the 1980s and 1990s, giving us an insight into what those family gatherings may have sounded like.

Regarding her change of heart, Kampire, spent years studying in the US and may have found music to be a powerful way of staying connected to friends, family, community and memory. But Ndola explores music as a point of cultural and generational tension in more ways than personal feelings towards styles like kalindula, which feature a mixture of “rural guitar” and chart pop, which grew in popularity during the Presidency of Kenneth Kaunda who mandated that 95% of songs played on the radio should be made in Zambia.

That model was repeated elsewhere on the continent. Notably in Zaire, now Democratic Republic of Congo, under President Mobutu Sese Seko, whose policy of authenticité or Zairianisation strictly controlled what could be played, favouring domestic work. An attempt to cure the colonial hangover, simply put, you were hearing it whether you liked it or not. A boom in demand for musicians, combined with instability, persecution and war, mean a significant diaspora of talent spread throughout neighbouring nations.

Decades later, genres remain popular across the region, and the Congolese rumba, perhaps the most famous, makes itself known on Ndola, alongside its offshoot, soukous, best described as the long lost soundtrack to the best night of tropical cocktails you’ve never had. Yet. The combination of guitar licks and melodic vocals riding on invitingly broken percussive grooves projects an aura of “no stress”. Maybe even reaching to “have another”. Pembey Sheiro’s ‘Sala Ni Toto’, a disco powerhouse by any other name and a highlight on this album, adds to that by showing just how persuasively synths can lead the genre out onto the dance floor.

Elsewhere, South African artists General M.D. Shirinda & Gaza Sisters also deserve specific mention. Shooting to global fame after Paul Simon recorded ‘I Know What I Know’ for his divisive but groundbreaking 1986 Graceland album based on their music, here they appear in all their shangaan, call-and-response, style glory on the track ‘Mabazi’. Kampire’s choice to include this is a nod to the overall impact South African music has had on her, home to the continent’s most influential DJ and dance music scenes as it is. A stylistic lineage can be traced from this hypnotic disco-fied surf rock gem to today’s amapiano via house derivative kwaito. The latter was a sound that flourished first in Pretoria and Johannesburg during the immediate pre and post-Apartheid years, the strength and dominance of South Africa’s dance music culture and, increasingly, domestic industry is seen by some as a symbol of resilience, community-as-defence, and freedom of expression. And, more recently, shangaan itself has been distorted and disrupted to produce a mutant electro strain that, at times, throws together super-fast beats, pan synth flutes and chants.

Ndola emphasises the need to acknowledge and learn origin stories to gain a deeper understanding of how music works both locally and globally in the present. Far from just another spectacularly re-playable adventure from Kampire, this is the most convincing evidence to date that she’s an excellent musicologist and historian, not just an exceptional DJ.