In Tim Robinson’s comedy show I Think You Should Leave there’s a sketch called ‘Game Night’ featuring Tim Heidecker as a character called Howie; it goes to great pains to indicate Howie is Not Nice To Be Around. He demands the host go up to the loft to get a nutcracker for the walnuts he’s brought from home and says things like, “Your record collection’s very meat and potatoes, Liz”. He has a ponytail and works at a tobacco shop. The reason? He’s a jazz fan.

When the group play The Hat Game, he’s astounded they haven’t heard of ‘household names’ like ‘Roy Donk’ or ‘Tiny Boop Squig Shorterly’ and can’t get clues like ‘he played the alto sax with the kink in it’ and ‘he’s got the freak lips that can hit the high C all night long’. Listening to and writing about jazz can feel like intruding on a private club with arcane rules and etiquette populated by Howies.

So when I saw my favourite jazz album – Charles Mingus’ The Black Saint And The Sinner Lady – was being reissued, the initial blaze of time-to-pitch hubris was dampened by the knowledge I am an avowed dilettante of the genre. To me, jazz often seems separate from the rest of music. A pretty insufferable man in a record shop queue (where else?) once told me he had one sound system for jazz and one for “everything else”. I think jazz is to music what Gaelic football is to football (vinyl collecting is soil stack maintenance, if you were wondering). It’s a formidable genre. Jazz musicians are known by their last name as a gesture of respect: Monk, Davis, Coltrane, Coltrane. Their reliefs seem hewn into the rock face of culture as venerable masters of form and composition.

A cursory glance through reviews on popular jazz publication websites turns up phrases like “trading eights” and “ballad mode”, as well as references to tempo and incessant categorisation of players and their instruments. “Mercurial flights in the upper registers" was about as flowery a description as I could find. The sum total of my usual analysis consists of deciding how often I can get away with writing “motorik” in one paragraph.

The Black Saint And The Sinner Lady, however, is an ideal record for your common or garden listener. The four tracks are linked by an array of repeated passages resembling loops that are typically interrupted by wild about-turns into something looser and more complex, before the ‘loop’ starts again. This structure reminds me of a Squarepusher (another protean bass talent) gig I saw recently. Thunderous rhythms were interrupted by bass improvisation before reasserting themselves; back and forth this went in dynamic badinage. Similarly, The Black Saint And The Sinner Lady’s bustling rhythms in ‘Track B’ lean into a hard bebop style followed by a skeletal trumpet refrain, before the arrangement slows to half-time, which is followed by a sped-up version of the ‘Track A’ intro; in this way it’s almost explanatory: ‘here’s this bit, then that section, then this bit’.

Although a lot of jazz can sound like a rotating cast of performers busying themselves with complex parts playing roughly in time (it’s just us here, go on, you can admit it too), The Black Saint And The Sinner Lady is full of mood and structure shifts where you understand something has happened. The giant, lightning-fast descending scale in ‘Track B’ is orchestral and epic, juxtaposing the preceding woozy horn intervals. Like a Sabbath riff, this run is executed with all instruments playing in unison. It has a similar vibe to the edificial salvo of Beethoven’s 9th symphony, like a musical command to ‘listen up’.

Repeated key moments function as The Black Saint And The Sinner Lady’s choruses – both in the musical and theatrical device sense. These include the iconic contrabass trombone rasp, the twittering flute ostinato, the dissonant two chord vamp, and the manically-strummed nylon guitar part. In 1963 The Black Saint And The Sinner Lady anticipated the Beach Boys’ fabled SMiLE album in which melodic refrains were recycled and reworked throughout. Whereas Brian Wilson and Van Dyke Parks detail a trip from Plymouth Rock to the fabled West, The Black Saint And The Sinner Lady seems to track these characters’ journey through a freewheeling, Dioneysian nighttown, from bar to club and beyond, suffused with a kind of darting, hyper-active focus suggesting acute lack of sleep.

Mingus’ ability to create these tone paintings in The Black Saint lends the music a cinematic edge. There are passages recalling the mournful decadence of Martin Scorcese, Baz Lurhmann, or Sophia Coppola. You can almost hear a narrator say, “Well New York back then was a real trip, I was just out there hustling, looking to pick up a dollar or two, and Jimmy, well, Jimmy was a thief.” Mingus even performed with a spoken-word accompaniment, the beat poet Kenneth Patchen, a few times. There are moments on this album where the music evokes a pan upwards from a bustling speakeasy through a grate on the pavement, above the buildings, with the city sprawled beneath. The gorgeous piano piece on ‘Track C’ – all lazy suspended chords and jarring fifths – suggests true nighttime has fallen, the odd trumpet squawk and cymbal susurration like laughter from departing revellers in a deserted side street.

I’m not too bothered if this is surface-level listening. These moments are clearly given focus. Listeners with fresh ears might miss specific techniques but can perhaps more easily settle into a blueprint laid down by the music, rather than get hung up on preconceived notions of form or style. Bill Evans once said “jazz isn’t a ‘what’ it’s a ‘how’” and this seems appropriate when listening to The Black Saint. For those unburdened with years of immersion in its lore, jazz serves as the medium rather than the meat of this album. Of course, it could well be that as an infrequent enjoyer of jazz, clearly-defined, repeated phrases are simply more listenable, like clocking the odd ‘bon soir’ in a French language film. However, I see their deployment as a moment of circularity that tempers the excesses of improvisation; The Black Saint is self-sufficient, existing in its own space.

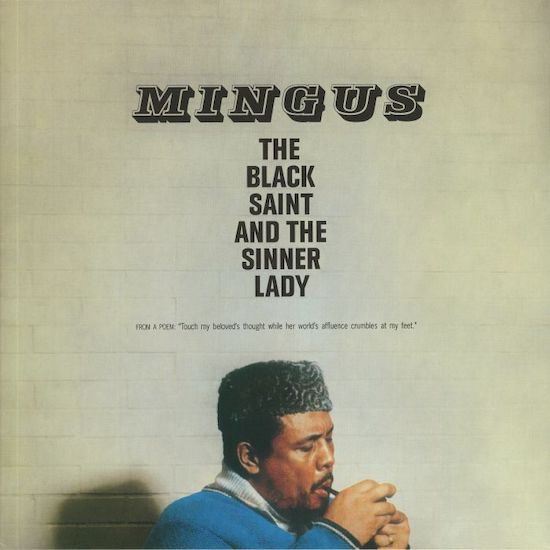

Throughout his career, Charles Mingus was determined to be labelled a ‘composer’, not a jazz musician. Whereas jazz album sleeves often feature their creator playing their instrument, eyes closed, sweat-drenched, deep in the heat of the beat – see Kind of Blue – it’s telling that The Black Saint and the Sinner Lady has Mingus calmly smoking his pipe, the hulking musician framed small next to the naturalistic shadow he casts on the wall.

In the liner notes Mingus writes that The Black Saint is ‘my living epitaph from birth to the day I first heard of Bird and Diz’ (Charlie Parker and Dizzie Gillespie). This suggests its prime mover is not jazz. Mingus dubbed it ‘ethnic folk-dance music’, a looser and all-encompassing term – I don’t think you need to analyse this peculiar nomenclature, just notice how he doesn’t call it jazz.

Significantly, the stand-out moment is not some scorching, spidery trumpet solo. Instead the album’s iconic refrains are relatively simple and played on flute and nylon-string guitar – i.e. atypical jazz music instruments. In Let My Children Hear Music’s liner notes Mingus writes about how using “uncommon instruments would open everything up". It’s an album that shuns unfeeling intellectualism, with Mingus sometimes playing root notes on the bass (a rarity in jazz) for more power and directness. Flamenco guitar chords that seem almost pasted over the jazz backing forcibly dislodge The Black Saint from any specific style that has come before – another of Mingus’ ‘listen up’s.

The Black Saint adheres to some of Mikhail Bakhtin’s criteria for the carnivalesque including “multi-toned narration, the mixing of high and low, serious and comic; the use of inserted genres – letters, found manuscripts, retold dialogues, parodies on the high genres… a mixing of prosaic and poetic speech”. At the start of ‘Track C’ the piano plays a gorgeous set of chords before interrupting itself, running through random notes and teasing the imminent flute piece (a kind of sonic world-building) before the player slams his hand down, mashing bottom keys with a jarring cronk. The Black Saint seems to relish this clash of high and low. Bakhtin’s criteria of ‘inserted genres’ is relevant to the overdubbing, tape editing and splicing on this record. Let me be clear: this album doesn’t have the caustic electronics of a tape-manipulated This Heat song, for instance, but Mingus still subverts the typical one-take method in his quest for sonic perfection.

Paradoxically, The Black Saint And The Sinner Lady is a very vocal instrumental record. Some trumpet parts sound like they’ve come to life and are trying to break out of their natural confines, with a cadence of laughter and talking – you can almost make out words. If it is an album of musical conversations then the culmination of ‘Track B’ is an argument (the panning is pretty mental on this record btw) – in the left can, bass and drums exchange barbs with saxes, while in the right, trumpets bicker and moan. The half-speed rhythm that starts to speed up is like the building of an argument, a veritable, “Hang on, what did you say?” in a musical language.

There’s a sense of the album being part of something bigger with its frequent inhabiting of this separate, carnivalesque space where trumpets can talk, pianos interrupt themselves, and melodies are recycled/”retold”. The dilettante can be put in the same position as the enjoyer, since both are on uneasier ground with such dazzling dynamic shifts in mood and texture. The ‘whys’ – as related to Bill Evans’ quotation about jazz being a ‘how’ not ‘what’ – are the contextual appendages such as the ballet, the relationship between the ‘Black Saint’ and ‘Sinner Lady’, the fact it’s supposedly one single piece split into movements, and Mingus’ psychotherapist’s contribution to the liner notes. (Mingus wrote the album after being discharged from Bellevue psychiatric hospital.) These help turn it loose from being a pure jazz record. In short, both Howie and I are listening to Mingus music, not jazz music.

Darran Anderson in a tQ reissue review of Kling Klang’s The Esthetik Of Destruction writes that “Chance often plays a part… in shifting popular music onto different tracks”. However, in The Black Saint And The Sinner Lady innovation comes in a more elementary way such as the altering of an embouchure, a specific Latin scale, or alto sax overdubs. In the same way a scene in a book may be carnivalesque, for all the stark dynamics this has been cultivated over hours of work. The improvisation can only get so wild before it has its wings clipped by the imposition of new motifs or structural about-turn.

In the best Modernist tradition, The Black Saint has passages of immense technical prowess and adherence to form. Tom Moon in the ‘Black Saint’s Epitaph’ writes “He expected his soloists to carry the spirit of his melodies into their improvisations” that were “strictly reverent to the rhythmic pocket". Celebrated jazz bassist Gary Crosby calls it "programmed music". You can hear Mingus shout "goddamnit" during the ‘Medley’ because Jaki Byard momentarily ignores the score. Parts of this record are like a kind of jazz Rosetta Stone, detailing bebop, Dixieland, modal and free jazz. They are framed, however, as merely another panel in the album’s loose tapestry.

So perhaps the reason I like The Black Saint And The Sinner Lady is because it’s only just a jazz record. It’s approachable, though not to say undaunting. It moves violently between and beyond traditional jazz forms. One moment it adheres to a specific subgenre of jazz, say bebop, before moving into something languidly orchestral overlaid with sparkling Spanish guitar runs, from groaning cacophony to elegant duet. Furthermore, his pioneering use of overdubs and recycled motifs negates the purely-instinctive purely-reactive solipsism jazz can be accused of. It’s an album that carves out a separate, third area beyond the constant timbral, emotional, and structural counterpoint. Gary Crosby says the band “maintain the sense of The Black Saint and the Sinner Lady, whatever that is”.

Mingus’ psychotherapist Dr. Edmund Pollock writes in the liner notes that, “It must be emphasized that Mr. Mingus is not yet complete. He is still in a process of change… One must continue to expect more surprises from him”. The Black Saint is a mess of change and antimony right down to its title: the most vocal of instrumental albums, the most meticulous free association, an album which is formless in terms of rules but with a grand, underlying, almost fractal structure consisting of tracks, movements, motifs, and voicings, occupying a space of its own that’s part jazz hagiography part jazz heresy. As Howie might say, The Black Saint And The Sinner Lady is absolutely “off the map”.