This compilation may look like a CD, but it is really a record. A record of the early to mid-1980s, an effervescent moment of conflagration, when youth culture was busy hurtling forward, almost hysterical with delight at the multiplicity of audio tools and textures suddenly available for mutating music.

The primal thrash of punk was a howl of rage and hope, a deliberate pop year zero – but after it, what deluge? Inevitably, perhaps, there came a natural urge to more sophistication or complexity, coupled with new musical technologies and a new availability of music, just in time for sampling, which coincided with the CD format. London was moving into Thatcherism and in New York, the Reagan cuts were decimating arts education (sounds familiar in 2013, too?). In every Anglophone territory, social constrictions were forcing creative underground youth to invent sounds that yelled Resistance! in disparate voices and beats. However, in Paris, there was a sense of expansion that encouraged a parallel process. The leftist Mitterand had taken over from Giscard d’Estaing, and hope and creativity pulsed through the capital’s boulevards.

In the hilly 20ème arrondissement near the Porte de Lilas, in a quartier populaire of Paris, was the cramped, messy office of Celluloid. The label’s leaders were an odd couple: studious, courtly Gilbert Castro, a former Director of the Maoists, and the far more extrovert Jean Georgakarakos, a twinkly-eyed barrel of a man. He co-founded Actuel, a dynamic glossy monthly magazine of global news and arts, with their close friend, Jean-Francois Bizot. who was umbilically linked to Celluloid. A drop-out patrician who loved both the low and high life, the charismatic, visionary Bizot shared Karakos’ goofy humour and immense zest for life.

Among the foreigners drawn to Paris and the Actuel/ Celluloid crew was the éminence grise of this compilation, producer Bill Laswell. “Like Burroughs said, Paris in the early 1980s was Interzone; a free meeting space, like Tangier in the ‘60s. Africans, Arabs, Europeans and Americans all connected there. In a surreal way, it was a movement, but it was not documented. That experience is not something people really know about unless you were there, sitting at the table discussing what you were going to do tomorrow. People still don’t grasp what was generating at that moment in Paris,” Laswell insists.

This axis became a magnet for a madcap crew of thinkers pushing a new vision of a multi-cultural future, before the idea of multi-culutralism was tainted by egocentric extremists of all stripes. Back then, cultural fusion was simply a timely post-colonial idea and ideal which Celluloid Records, the fledgling Radio Nova and Actuel were all pushing.

No one was fretting about cultural appropriation, there was just an exultant sense of liberation as artistic connections sparked new musical breeds. But perhaps it took the French to conjure this particular scintillating synthesis. With a magpie energy, Paris was always more “branché” (hip) than other capitals when it came to appreciating and absorbing the so-called “Other”. Says Laswell, “It seemed to be the place where West Africans moved. All the artists came to Paris – as when all the free jazz musicians like Sun Ra, Don Cherry and the Arts Ensemble of Chicago found a second home there in the 1960s.” Laswell name-checks legends whom Karakos was instrumental in bringing to the world on labels like BYG. His eclectic perception of music, which found a kindred spirit in young Laswell, made Celluloid a completely unique cross-cultural mash-up label.

Pre-Celluloid, Karakos has built his business on shrewd importing: “It began with me going to Rough Trade in London, which was just starting up at this period. We would take the car Sunday evening to London, be at the store when they received new releases from each independent at 9.00am on Monday and I would fill my car full of singles from all of the independents at the end of the ‘70s – records like Gang Of Four, Cabaret Voltaire, Metal Urbain. On Monday evening, I was back in Paris and on Tuesday morning I was on the phone to call every store and sell them the records.”

“As a label, we started by releasing some reggae stuff from Jetstar. I had a very good relationship with the boss and he would give me some product to release in France.” Licensing in carefully selected records proved fruitful during Celluloid’s early days. Errol Dunkley’s ‘OK Fred’ and Soft Cell scored massive success. The crew also gravitated naturally to the authenticity of the hard-hitting funk messages from the archives of producer Alan Douglas – early Last Poets albums, Last Poets mainstay Jalal’s big pimpin’ Hustlers Convention LP and a rare one-off session featuring Jalal, Buddy Rich and Jimi Hendrix.

The Celluloid/ Actuel aesthetic hit the road at the start of the 1980s. Karakos explains, “I went on a trip to New York to sell Celluloid records to the chain stores and on my way back, I stopped to sleep over at my friend Giorgio Gomelsky’s house – he was the first producer of the Rolling Stones and had signed The Yardbirds among many other artists. When I arrived there, I saw a guy working up at the ceiling, painting. It was Bill Laswell. He was 22 or 23 years old at that time. I stayed there, he stayed there and we spent all night speaking with him. He said, “In America, there is nobody with guts who can go against the system and release good music, sell it and make it known so you should come and live here.” I went away the next day and thought how I had loved the conversation with him. He was a very young guy, really knowledgeable about music and he spoke really articulately. That influenced me very much. I saw it with my own eyes in the shops – there was nothing interesting in these big stores. Just mainstream rock, the same old shit all the time. So, I decided at that point to go and live there in the States.”

I arrived in September 1980 and the first guy I met in St. Mark between 2nd and 1st Avenue was Bill Laswell. He didn’t believe I would be there. A few days later, he says “I have something for you, Jean.” He met me and he gave me the tapes to Temporary Music, his new recordings with Material. He said, “That’s for you. That will help you to start your company here.”

Karakos’ move had been preceded by writer Bernard Zekri who had moved to the Big Apple as an advance guard of the crew. Tall and lanky with a mop of curls and smouldering poet’s eyes, Zekri immersed himself in the strongholds of hip hop in Queens and the Bronx. Enthralled by the emergent sounds there, he re-invented himself as a producer. Says Laswell, “Bernard Zekri was instrumental. By doing his research as a journalist and with his interest in New York culture, he reeled in things that Karakos liked to exploit. It was a new culture. When hip hop came downtown from Disco Fever to the Ritz and the Roxy, Karakos and Bernard were there, for sure.”

Zekri’s downtown apartment on 8th Street and 2nd Avenue was handy for Club Negril, a haven for reggae and hip hop. Many of the uptown ghetto stars who would soon storm Europe bonded while crashing at Zekri’s after a late night of clubbing below 14th Street. “I was one of the few who had a music background,” Laswell recalls. “They were non-musicians, but they all had personality, charisma and confidence. It was inspiring coming into their world.”

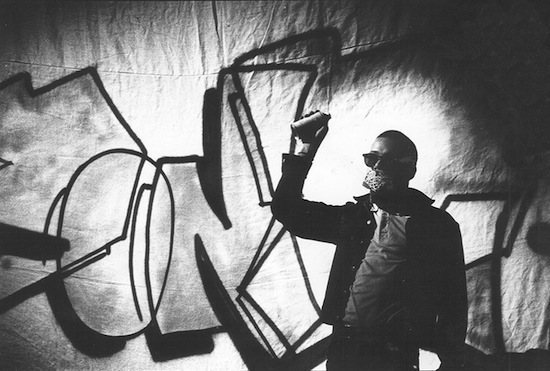

Zekri sent back vivid reports from hip hop’s Front Line that whetted the curiosities of French hipsters. Thus it was the Celluloid/ Actuel axis that orchestrated the groundbreaking tours of Europe which introduced the triple-threat of New York’s underground, all ready for its close-up with a killer combo of break-dancing, graffiti and an aural assault of mixing and rapping. That road show electrified kids at every stop, and shifted their thinking.

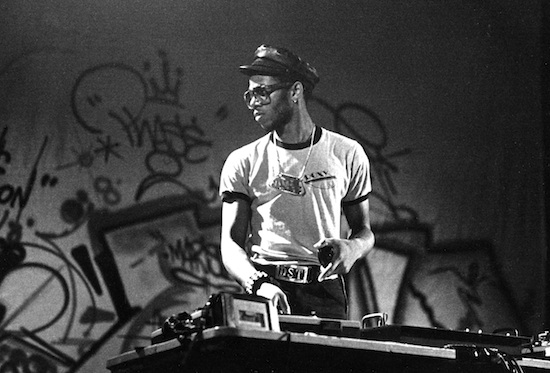

On assignment for weekly music paper, Melody Maker, London photographer Janette Beckman took the tour photos that adorn this compilation. “By then punk in the UK was on the wane and we were all looking for the next thing – and here it was! A renaissance, brand new ideas coming from a similar root to punk,” she says. “New York City was experiencing a bad economy, huge unemployment – and these were kids from working class backgrounds inventing a completely new kind of music. There were scratch DJs, double Dutch girls, graffiti artists, rappers, with great styles and new attitudes. Shortly after seeing the show I moved to New York City and that was the start of my documenting the early old school years of hip hop."

Encouraging such conversions was Zekri, by now a downtown svengali and cultural translator. He corralled Americans to perform in French, including cool girl B-Side aka Ann Boyle, whom he would later marry, golden-voiced Bernard Fowler and graffiti artist / rapper, Fab 5 Freddy Braithwaite, whose much-sampled ‘Change The Beat’ gives its name to this collection. Karakos remembers the session: “B-Side just took the mic to show how to sing the title line in French, ‘Change The Beat, Change The Beat’. Everybody was so surprised and said, ‘let’s keep that’ so we ended up keeping one version in English and one in French. B-Side was American but her boyfriend was Bernard, a Frenchman, so she knew how to speak French and we could understand what she was saying.”

Celluloid quickly became a haven for boundary-bending musicians. The freewheeling, open tone of the label’s identity was set by its colourful founder, Jean Karakos. A controversial prankster of the old school, he had already been turning people on to unexpected music since the 1960s. Infamously, his astute ears and aesthetic were matched by a piratical, cavalier approach to business that landed him in court more than once. Yet even his roughest critics had to admit that Karakos knew what to pillage. His taste was, as the French say, “impéccable”. That the French audience had access to the New York avant-garde, adopted and was shaped by it, even before much of the U.S. knew it was happening, was down to Karakos.

“With Celluloid, I knew the artists, the artists knew me and I had one trait through my career – I never released a piece of shit,” he affirms. “If I worked on or released a record, it’s because I believed in it. Maybe I’m wrong, maybe I’m right, but at least the people know I’m sincere and I’m not trying to sell them stuff because I have too much stock.”

Though hits were, of course, welcome and desired, Celluloid never strategised specifically for the pop charts. In a gloriously old-school way, the label went on its gut. If kids were having fun in some dodgy, run-down urban area, and their art was electric, Karakos or his emissaries like Zekri and another branché French manager/ producer, Martin Meissonnier were there; ready to pluck cultural blooms struggling through cracks in the concrete and transplant them to Paris.

Karakos also continued to work regularly with Bill Laswell. He grew into a sound constructor for a wide range of artists seeking an experimental edge – Laswell would genre-hop from Paris to the Bronx to SoHo to Africa to Chicago to put his imprint on many of this compilation’s tracks. “Bill Laswell was the heart of the label,” states Karakos. “He was a lot younger than me, but I understood he was very mature and he was so serious with music. Music for him was everything. It was music first, then after came drinks, women, whatever else. For Bill, music was the God, even at 22 years old.”

With his own bands like Massacre and Material, Laswell effected testosterone-fueled deconstructions of funk and blues alongside musical extremists like drummer Roland Shannon Jackson and guitarist Sonny Sharrock and saxophonist, Peter Brotzmann. Like a progressive Pied Piper, Laswell coaxed drummer Ginger Baker out of retirement and got him playing with the Laswell rhythm section – a shifting transnational crew including Gambian griot Foday Musa Suso, Cuba’s Daniel Ponce, Brazil’s Nana Vasconcelos, Bernie Worrell of Parliament-Funkadelic keyboard fame, together with hip hop’s Grandmaster D.ST. Perhaps its best known associate was jazz great, Herbie Hancock, whose revolutionary work with Laswell appears here. “Meeting Karakos was the beginning for me,” explains Laswell. ”It was the first time someone appeared who would actually finance things. It made a big difference. I could get things done. Karakos started a lot of experiments that definitely would not have happened without him.”

Linked by their shared love of free jazz, African music and blues, the two men became co-conspirators in capturing the blended sounds of our cities’ real, unsung communities. Of course, uncut hip hop was crucial. Tracks like D.ST’s ‘Home Of Hip Hop,’ featuring Rahiem and The Infinity Rappers, shouted for The Bronx well before the more celebrated war of words either side of ‘The Bridge’ by KRS One, the Juice crew and the rest. It remains a founding text of hip hop.

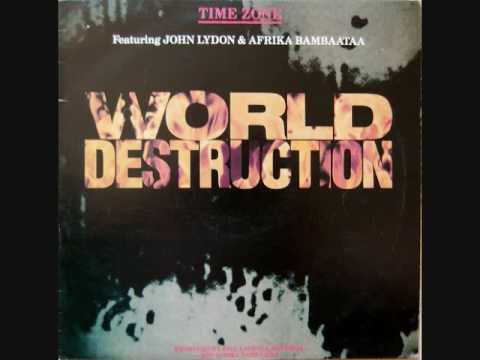

But Laswell also saw the possibilities in unconventional pairings and brought John Lydon to work with Afrika Bambaataa for the doomy fury of Timezone’s ‘World Destruction’. Their classic melding of UK punk with hip hop demonstrates how hip hop was already punk’s twisted twin, superficially dissimilar, but alike in roots and attitude. Punk’s raw power also appears here in the person of Rough Trade label founder and frequent Celluloid licensing source, Geoff Travis, who co-produced Shockabilly’s freaked out version of the Fab 4’s ‘Day Tripper’; The Clash appear too, jamming with graffiti artist Futura 2000 on a track that tells the story of a man and a movement, ‘The Escapades of Futura 2000.’

The Brits understand the DNA-deep link between punk and reggae. Dennis Bovell who appears here in his Blackbeard persona alongside Winston Edwards, represents UK reggae on ‘Downing Street Rock’. He is a leader in the UK’s first generation of West Indian descent, who forged their own brand of reggae to express their confrontational reality. At the same time, in Paris, musicians from the former African colonies were starting to culturally infiltrate their old slave masters’ haunts. Paris became a two-way post-colonial rampage, with African artists eagerly embracing electronica and jazz, just as the French, English and American artists were exploring the cornucopia of African grooves. Among them and featured here are Toure Kunda, Senegalese ex-pats who were and still are pivotal in the Afro-Paris scene. Working with Karakos, they graduated from intimate Paris boites like New Morning to play vast stadiums as Ambassadors of Africa. African original legends were not neglected by Celluloid, either. The hypnotic ‘Abele Dance’ by Camerounian grand master Manu Dibango, was just one of the Afro-electro dancefloor hits then produced by the scenemaker, Martin Meissonnier. Such fusions irritated purists and awoke global clubbers to the might of African music.

Karakos played a part in opening America to non-Anglophone music. “Slowly, after many conversations, they started to increase the world music division in the Tower record stores and it became a big part of their business,” Karakos recalls. “Buyers originally just thought tribal music, field recordings. But the mix of traditional music with pop and new modernity was a big area – that was the mixture which made it interesting for the American market. “

Disclosure: I too was an Actuel writer and Celluloid artist cutting multi-culti songs. Sadly, scheduling conflicts prevent my duo with Eve Blouin, Chantage, from appearing here – though seek and you shall surely find! Eve and I had an African music radio show, Chéries Noirs, on Actuel’s pirate station, Radio Nova, (now one of France’s premier radio destinations.) This set features Bobongo Stars from Zaire’s ‘Koteja,’ a sprawling, seductive mix of village harmony and percussion with horns, rock guitar, synthesizer and funky bass that defines the experimental era. It was a big tune for us.

In those early 1980s, the burgeoning UK/ US electronic music scene that so intrigued the Africans was starting to shape the pop charts. Here, its purest form is found in Thomas Leer and Robert Rental’s ‘Day Breaks, Night Heals,’ originally a 1979 release on the UK’s Industrial Records; the aesthetic wielded by Celluloid was expressed by its licensed artists as much as its own signings.

But, intrigued as the label was by international music, they still served their home community. Our selection shows the Paris sound to be sparse, moody and inventive. French artists like Nini Raviolette were influenced by the louche experimentalism of Manhattan downtowners’ mutant disco, in which conventional tropes blearily swayed in a shimmering distortion of known dance modes. A sultry night-life presence in Parisian boites, Edwige, stalks elegantly through Mathematiques Modernes’ ‘Disco Rough.’ All the jerky electro dissonance that we love in synthesizer post-punk bubbles in Ferdinand Richard’s funny, apathy-ridden ‘Tele, Apres le Meteo’.

Whether near or far from home, Celluloid fitted in just fine. Looking back, this eclectic Celluloid sensibility was part of the evolution of a gang of young intellectual “gauchistes” who believed in revolution. Forged on the barricades of the student riots of the 1960s, Karakos, Zekri and Bizot, along with Meissonnier and the rest of the crew, were devoted to discovery and revelation. The eccentric, compelling and hilarious denizens of this record are a reminder that, in every generation, we must always continue to ‘Change The Beat.’

Vivien Goldman, January 2013 – Sleevenotes for Change The Beat: The Celluloid Records Story 1979 – 1987 out now on Strut

Various Artists – Change The Beat: The Celluloid Records Story 1979 – 1987

You only have to listen to the first couple of songs off this compilation to sense its efficiency as a portal to a more open minded, musically eclectic and optimistic time and place. The opening salvo is a cover of the Beatles’ ‘Day Tripper’ by Shockabilly, (licensed by Celluloid from cult New York indie Shimmy Disc) featuring one time Butthole Surfer, B.A.L.L. and Bongwater bassist Kramer; free jazz banjo enthusiast Eugene Chadbourne and Klezmer drummer David Licht. The trio indulge in a ridiculously gonzoid exercise in deconstruction that sits somewhere between Beefheart and Pussy Galore. Then from lysergic looseness, we switch to amphetamine strung post punk jazz metal courtesy of Massacre’s ‘Killing Time’. While obviously not at the same level of heaviness as more recent highly technical, jazz and avant garde influenced rock bands such as Shining (No) and Zu – in 1981, Bill Laswell, Fred Frith and Fred Maher were cutting a brand new path that sounded like Sonny Sharrock jamming with Wire and Doug Wimbish.

And on it goes… Naming the first ever hip hop song recorded is an idiot’s quest if ever there was one but if you want to hear something that was probably as important an influence on the development of the N.W.A. aesthetic as Iceberg Slim paperbacks and Blowfly routines, then check out Lightnin’ Rod’s ‘Sport’ (originally from the excellent 1973 album Hustler’s Convention). Lightnin’ Rod was basically a pre-spiritual awakening Jalaluddin Mansur Nuriddin of The Last Poets rapping proto-gangsta rhymes over music provided by the likes of Tina Turner and the Ikettes and Billy Preston, some 14 years before Dre, Cube et al hit the studio. This track, backed by an instantly recognisable Kool And The Gang deals with the protagonist’s formative years: “I had learned to shoot pool/ Playing hooky from school/ At the tender age of nine/ And by the time I was eleven/ I could pad-roll seven/ And down me a whole quart of wine./ I was makin’ it a point/ To smoke me a joint/ At least once during the course of a day/ And I was snortin’ skag/ While other kids played tag/ And elders went to church to pray.”

From the French side of things there is a clutch of punk funk, post punk, electro and cold wave gems with Mathematiques Modernes’ ‘Disco Rough’ coming on like Belgian neighbours Telex; the excellently named Modern Guy laying down herky jerky James Chance contorted funk on ‘Electrique Sylvie’ and Nini Raviolette making breathy and sensuous electronic music that’s part cold wave synth pop and part space age lounge on ‘Suis Je-Normale’. There are some big names from this side of the channel including John Lydon who froths at the chops on the still stupendous ‘World Destruction’ by Time Zone; an understated Ginger Baker number ‘Dust To Dust’; Brit reggae production master Dennis Bovell (as Blackbeard) teaming up with Winston Edwards and The Clash doing the only thing they were ever any good at: making dance music. (They appear as backing band to Down Town Manhattan graffiti artist Futura 2000, who certainly had wilder skills with the spray can than he did on the mic.)

The best tracks here are courtesy of a real colonial culture clash however, African master musicians Toure Kunda, Bobongo Stars and Manu Dibango engaging with the French and New York underground on their own terms. If Hemingway’s Moveable Feast had literally lived up to its name and ended up in late 70s bohemian Paris and early 80s art gallery Manhattan, then this would have been the soundtrack. If this music were being released now most cultural commentators would be pissing their pants about cultural appropriation, middle class entitlement, authenticity and hipsterism but thankfully only those with too much time on their hands will start applying these tenuous criteria to music retrospectively.