Many bands suffer from the ‘classic line-up’ phenomenon, and Can are a classic example of it. In the alternative rock canon, the three and a half albums the band made with Damo Suzuki in the early 70s have come to be revered as holy relics – not just records of enormous invention and influence, but sonic touchstones that musicians and fans of good taste must all nod their heads sagely about and pay due respect to. Blurting out that perhaps Tago Mago might have worked even better as a single LP remains a positively heretical statement.

There’s another and much longer essay to be written about how these albums have come to be viewed with this near religious intensity, but its upshot has been to solidify the notion that the Damo-fronted Can is the ‘classic’ version of the band, and that their output following his departure must therefore be diminished in comparison. This has detracted attention away from the rest of their catalogue to the extent that plenty of ‘Can fans’ out there haven’t even investigated their post-Damo output.

Given just how ground-breaking and head-spinning much of Can’s Damo-period music is, it seems curious that this should be the case, as though assuming the band must have immediately lost its spark and direction. But this is one of the main symptoms of the classic line-up view of history. It’s as though we find it easier to compartmentalise our enjoyment in a way that’s weirdly parochial – which is ironic in the extreme given Can’s genre fluid approach to music making.

I too was once a staunch adherent of the Damo orthodoxy until I came across a CD promo of their 1977 album Saw Delight, going for a quid in a Manchester record shop. I didn’t have any great expectations for it – but after just a few plays, it quickly became my go-to Can album. To my ears at least, it’s a wonderful distillation of what made those Damo albums so compelling: metronomic rhythms and sinuous instrumental interplay, yes, but also that slightly arch European art sensibility. But there was something new as well, the arrival of bassist Rosko Gee and percussionist Rebop Kwaku Baah (both formerly of Traffic) imbuing the music with the type of Afrobeat/highlife vibe that Brian Eno and David Byrne would run with a few years later.

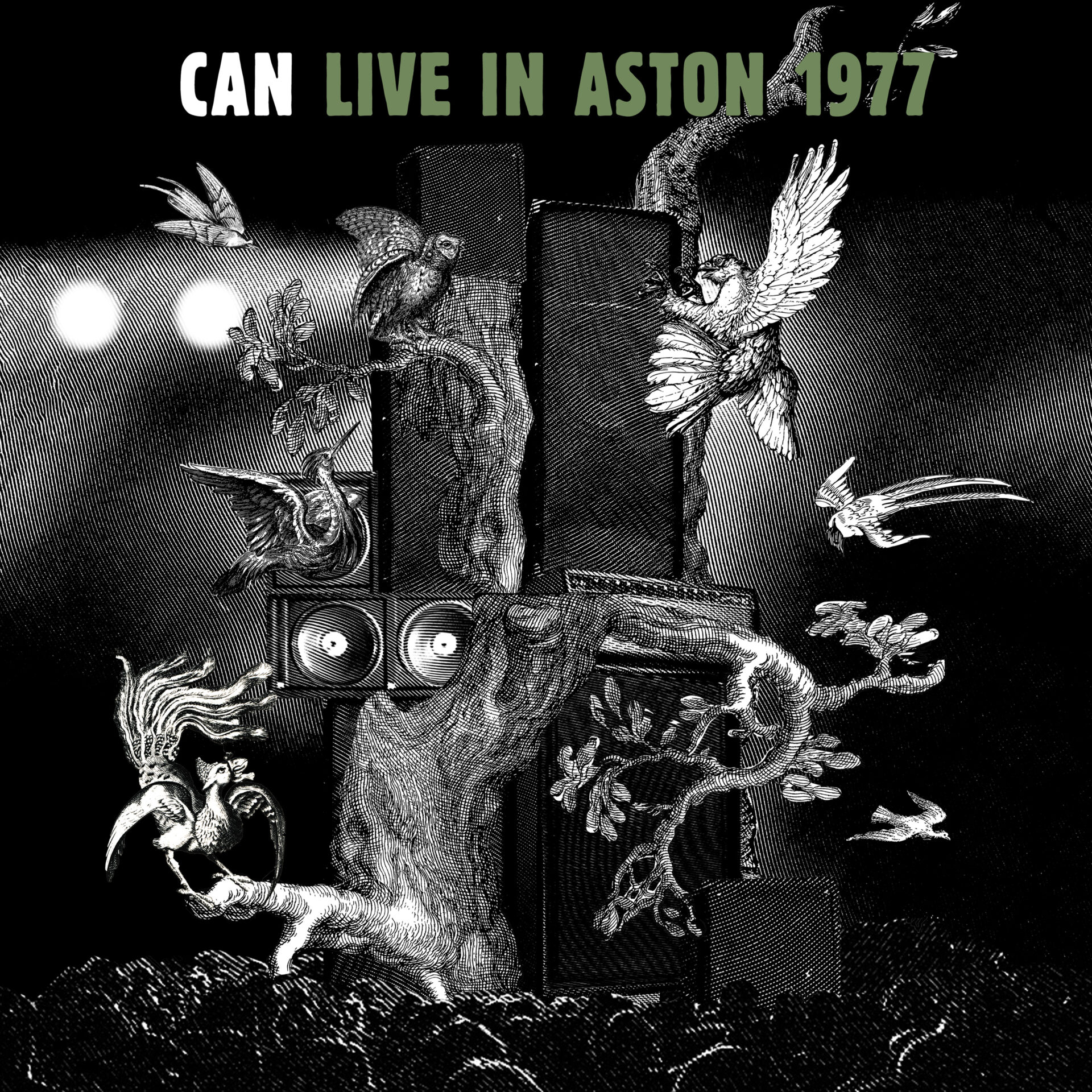

Which brings us to Live In Aston 1977 – or maybe it doesn’t. If there’s one thing that this ongoing series of live releases – of which this is the fifth – have made clear, Can on record and Can on stage were two different entities. Improvisation had always been at the heart of the band’s compositional technique, but this was a process that also continued every time they played live – in other words, there was no attempt to simply replicate what they had put on their albums. Instead, elements of songs were used as a springboard for new explorations, recognisable fragments emerging from the flow before morphing into different shapes and colours.

As such, Aston doesn’t actually bear that much resemblance to Saw Delight, released just a few days before this performance at Birmingham’s second university on 4 March 1977. Baah is absent and Gee is relatively low in the mix for the most part. But what it does share with Can’s later live sets – for instance, Live in Cuxhaven 1976 from the same series – is a feeling of spaciousness. Whereas the previous Live In Paris 1973, recorded at the end of Damo’s tenure with the band, features a performance veering between ritualistic frenzy and brain-pummelling monotony, Aston is ultimately a more inviting and easier to enjoy proposition.

As with all of these releases, the live pieces aren’t associated with studio songs, but simply numbered. ‘Eins’ begins with a nebula of Rick Wight-esque Farfisa organ from Irmin Schmidt and some exotic, vaguely funky vamping from Michael Karoli – in fact, this could be Pink Floyd just after the exit of Syd Barrett, psychedelic abstraction transforming into something darker. And when Jaki Liebezeit makes his entry, it’s not with a skittering polyrhythm, but a thumping, no-messing-around mid-tempo beat.

There’s the sense of a voyage beginning, the band channelling that aqueous sound they perfected on Future Days, but moving through colder, darker waters. Karoli’s guitar rises from the depths, half growling, half roaring, then spins and dips in the icy surf. There’s some horrorshow keys from Schmidt, and in the background, what sounds like a chorus of radiophonic cats – the first evidence of Holger Czukay, who, having given up his position as bass player, now experiments with shortwave radio and tapes in a proto-sampling role.

The track morphs into what can only be described as industrial reggae, leaner and meaner than the maximalist headjams of a few years before. Karoli returns to the foreground again, his guitar wrangling verging on the atonal, howling like a robot in distress as Liebezeit picks up the beat. It ends in a flourish of prog ska, which is much better than that sounds.

‘Zwei’ is a deconstruction of ‘Vitamin C’, beginning with some discursive jamming around the organ breakdown at its centre before that bassline appears. Rather than tightly coiled Krautfunk, this version is dreamier, almost ecstatic. There’s some surprisingly metallic guitar chugging at one point, but Karoli weaves dexterously around the main theme, like the sensuous caress of an old friend.

‘Drei’, the longest piece here, starts with a flurry of deep space organ from Schmidt, the sound filtered through his self-designed ‘Alpha 77’ effects unit – compared to previous releases, Schmidt feels more prominent in this set as the band’s overarching sonic architect. Then we’re into a sub-tropical groove, Karoli chopping out a hard funk riff against a strange cacophony of noises and disembodied voices stolen from the airwaves. It all adds to a slightly uncanny vibe, organ swells suddenly looming out at us ghost train-style.

Karoli steps up again, his tone almost exactly halfway between that of Dave Gilmour and Robert Fripp, but in accordance with Can’s musical philosophy, it never feels like he’s just ‘taking a solo’, but adding instead to an ever evolving collage of sound. Yet if that smacks of hippie woo-woo, there’s something bracingly futuristic about the noise they’re making here, heightened by Liebezeit’s hypnotic playing.

The track threatens to lose focus, before the drummer takes control, executing some rapid snare and hat work against Gee’s murmuring bass and Schmidt’s sci-fi junk. You can hear the band lean into the weirdness as Czukay’s found voices become devotional cries from deserted temples. What sounds like a marimba chimes and oscillates at high speed as the track climaxes.

‘Vier’, the final piece, is a heavily reverbed version of ‘Dizzy Dizzy’ which soon moves into the fourth world, that mysterious interzone between continents and cultures. Organ and guitar spill over each other, wailing in the night like a particularly verdant take on Eno’s Another Green World. It’s undoubtedly music for mind expansion, but it stretches the brain in ways that remain unique – Can have always been purveyors of inner space rock, with each trip into the unknown as different as their shows.

Aston proves once again, as this series of albums no doubt intends to demonstrate, that Can remained a vital and adventurous band beyond the Damo era – in fact, throughout their entire existence as a live act, with the group playing their last show in May 1977. Damo may have been irreplaceable (and will always be in the ‘classic line-up’ in many people’s minds), but the spark that initially ignited Can still burned brightly on stage right up until the end.

![CAN - Vier [Live in Aston 1977]](https://thequietus.com/app/cache/flying-press/073ff3f1072dc8dc4f2fdb9ba8a5d35f.jpg)