Popular wisdom has it that the word ‘sabotage’ is derived from the practice of 19th Century factory workers throwing their clogs into the cogs of industrial machines, with the aim of kicking a hole in the side of production for a day or two. Typically however, popular wisdom hasn’t got it quite right.

According to John Spargo’s 1913 book Syndicalism, Industrial Unionism And Socialism, the word was coined in the 1890s by a French anarco-communist. Émile Pouget drew inspiration from the 19th Century British labour movement and suggested adopting a policy of purposeful inefficiency in order to put pressure on factory owners. The technique was already known across the UK by the Scottish colloquialism ‘ca canny’, and as there was no direct equivalent in French, Pouget suggested “sabotage”.

The term derived from the French verb ‘saboter’ or to make a “loud clattering noise” while wearing cheap wooden shoes. It was pejorative, altogether lacking in class solidarity, as it poked fun at the perceived clumsiness of rural workers, who stumbled noisily about in their ridiculous carved-ligneous clodhoppers, unlike their metropolitan counterparts pattering about gracefully in their leather shoes.

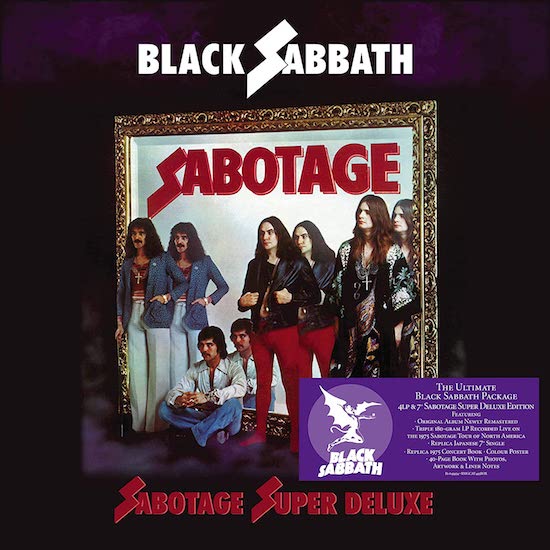

When Ozzy Osbourne clattered noisily on six inch wooden heeled boots to stand against a giant mirror with the rest of his bandmates in the Summer of 1975, was there any sense in which he was trying to derail the unstoppable juggernaut that was Black Sabbath? After all it was him who turned up to an album cover photoshoot looking like… well… a village idiot let loose in Oxfam?

Of course it’s not just him. Take a close look at the eyebrow raising sleeve now. Bill Ward’s chequered Y-fronts can be seen clearly through his wife’s red tights and while he is clearly and, unusually, clean shaven, he also looks like he has spent the previous eight hours removing each hair from its follicle, one by one, while sweating liquid cocaine out of every pore; it might be an impression created negatively by repro but his knuckles also look bloodied. The comparatively urbane Geezer Butler’s fashion choices are wild even for the day and the combination of low-cut knitted tank top, tightly permed mullet and voluminous moustache is particularly effervescent. I want to say only Tony Iommi looks normal except that he alone seems to have realised the sartorial import of the scenario. To say he looks angry is to stretch the word “angry” beyond breaking point. He looks like the head of a New Jersey construction and waste management empire who has just found out that his prospective son in law has been cheating on his daughter and is now contemplating his next move. He looks positively Mephistophelian.

The overall effect of the sleeve to Black Sabbath’s sixth album, Sabotage, is judderingly woeful. It’s as if the cover to Paranoid has blithely stated: “I’m the worst classic metal cover of all time…” Just for Sabotage to butt in: “Hold my pint of Ruby Mild…”

The original concept for the cover was solid enough. Sabs roadie Graham Wright helped crystallize the idea of the band, clad in bible black, recreating the René Magritte painting, ‘La Reproduction Interdite’, staring out of a mirror surrounded by stained glass, at the end of a gloomy castle corridor. But the road to hell is paved with tin-eared label lackeys and skimped details; certainly the English translation of the Magritte painting – ‘Not To Be Reproduced’ – suggests that the Belgian surrealist had the last laugh from beyond the grave.

Vertigo failed to arrange a castle, or even a gloomy corridor for that matter. Instead they hired a Soho photo studio for the afternoon. Perhaps sensing keenly the corners cut, they also failed to tell the band that this was the location for the photoshoot itself, instead suggesting that they merely wanted to discuss art direction for the album.

“It would have been a good idea if they’d told us we were having our picture taken”, Geezer Butler told Q Classic: Ozzy – The Real Story in 2005. “It was somewhere in London. We thought we were just going to talk about the album cover – but they shot it, and nobody had any other clothes with them.”

So the sleeve wasn’t an act of self-sabotage at all. But that raises another question: who turns up to a business meeting looking like this? This is a snapshot of a band – Osbourne, glassy-eyed, uncomprehending, barely there; Ward, drill-bit eyed, near psychosis; Iommi, marinating in anger, one fucking straw away from the camel’s spine splintering; Butler, tired, exasperated, no longer astral traveling, just trudging along corporeally – who are totally besieged. Like Wile E. Coyote, they have long since run off the cliff’s edge, their legs motoring away ineffectively as they hang above an abyss.

Popular wisdom has it that Sabbath peaked with Master Of Reality and went into freefall directly after Sabbath, Bloody Sabbath, and often people who trade in popular wisdom don’t look beyond the sleeve of Sabotage when looking for evidence to back this up but of course, for those listening, the band’s sixth album is the bookend of their true imperial phase. As superb as it is, Master Of Reality still sounds like it was recorded in a breezeblock shit house by a tin-eared cretin and, in terms of production, it’s only really with the release of Vol. 4 that you can sense the lightbulb flickering into life above the collective heads of NEMS/Vertigo: ‘Ahhhh… we get it now… this pulverising style of thuggish rock music isn’t just some passing, schlocky, Satanic sub-blues fad but a new popular artform in its own right…’ So while the early cheap recordings suit, if not enhance, tracks such as ‘Black Sabbath’ and ‘Iron Man’, the Sabs only really get the kind of full-spectrum studio treatment they’d always deserved by the recording of Sabbath Bloody Sabbath and Sabotage.

To my mind, there is a drop off in quality from Sabbath in the mid to late 70s but I’m not one of these indie dweebs who can’t cope with the mighty voice of Ronnie James Dio. So for me, the true story is a matter of seeing Technical Ecstasy and Never Say Die! as a temporary fall from grace before they come sailing back upwards with Heaven And Hell. If I were to draw this as a graph with the cosmic might of Black Sabbath portrayed on the y-axis and time’s inexorable progress on the x-axis, then the actual shape would resemble, not so much a low-pass, as a band-stop or band-pass filter. In musical terms, one of the more remarkable things about the ‘cutoff’, or violent downward slope of either a low-pass or band-pass filter is the effect an internal feedback loop known as ‘resonance’ or ‘Q’ can have on the sound. As resonance is increased, the filter starts generating its own tone through a process of self-oscillation, paradoxically, as the overall sound starts weakening, things actually get more sonically interesting just before they nosedive into the abyss. And so it was with Sabbath as they stood on the verge of their unsatisfactory final two albums of the classic line up.

Of course the band themselves weren’t really that keen on the album, unable to divorce the unpleasantness of the experience of recording it and how taxing being in Sabbath had become by 75, from the resultant collection of songs. But really, to me Sabbath Bloody Sabbath and Sabotage represent the resonant phase of the band.

The band of course felt that the actual sabotage being wrought upon them was courtesy of those charged with looking after them. Regarding management they originally swapped inexperienced and out of his depth club promoter Jim Simpson in 1970 for Patrick Meehan, only to realise he was taking, let’s say, more than his fair share. After that they threw their lot in with Small Faces manager Don Arden in 1974. Not yet realising that in management terms they’d leapt decisively out of the fire and into a particularly grim frying pan, while they were recording Sabotage their main aim was to retrieve Smaug-like piles of cash back from Meehan and his World Wide Artists company. The band recorded their album at night time, not to save money but simply because they had to attend court during the day. Ozzy Osbourne’s feelings about how the band was being run during this period can be gauged reasonably well by listening to ‘The Writ’. And of course, the band who by this time had broken America, were setting off on longer and longer international tours. Sabbath – who created a whole new genre of music and released two albums during 1970 – were quiet on the release front in 1974 simply because of their touring (and narcotics) commitments.

Ten months in all the legal battle lasted and the band have since expressed surprise that they got one song written in that time, let alone eight. But if it proves anything to me, it’s that Black Sabbath continued to thrive under pressure. During the recording Iommi went deeper into the production side of things, working with Mike Butcher and Spock Wall on his guitar tone, retreating from some of the progressive experimentation that had typified Sabbath Bloody Sabbath, the glorious evidence all over ‘Hole In The Sky’. Often mistaken for an ecologically-minded warning, ‘Hole In The Sky’ is actually evidence of Sabbath forging yet another aesthetic pillar of heavy metal. After minting metal’s weight (‘Black Sabbath’) and speed (‘Paranoid’), ‘Hole In The Sky’ represents the creation of an unshakable metaphor: apocalypse representing the collapse of the individual ego. As life is reduced to a Hellish struggle only the idea of the end of all things offers any respite from the punishment. It is a frontline report from a mind so degraded and despondent that it imagines not a hole in the ground which can be crawled into but a hole in the sky that will suck in all matter.

After the chiming minimalism of ‘Don’t Start (Too Late)’ – the title a literal instruction to studio tape operator David Harris who complained the band often started playing before he was ready to record them – another unassailable peak is ‘Symptom Of The Universe’, a greasy, low slung chugger, that effloresces effortlessly into a Balearic psych jam, satisfied that it has already contributed a fundamental building block for the foundation of thrash metal, to be laid alongside ‘Into The Void’. The power displayed here is cemented by two no-bullshit ragers ‘Megalomania’ and ‘Thrill Of It All’.

One of Iommi’s big complaints about Sabotage was that without the court case, the band could have kept on stretching their wings and carried on the process of Sabbath Bloody Sabbath’s experimentation, which kind of ignores the presence of the English Chamber Choir and a harp on ‘Supertsar’. Iommi originally wrote the instrumental track on his mellotron but then ended up booking the choir to complete the track. No one warned Osbourne about this extravagant feat of studio experimentation and when he walked in during recording, he assumed he had the wrong studio and left again.

As much as it points forwards towards a lot of weak moments in his solo career, ‘Am I Going Insane (Radio)’ is one of Sabbath Mk I’s catchiest numbers and makes for an interesting album closing pair alongside ‘The Writ’. Tonally, the breadth represented by these two tracks shows just how far Sabbath had travelled as a group, and that – wooden shoes and red tights notwithstanding – no amount of internal or external sabotage could interrupt the stellar course of Black Sabbath’s majestic transit just yet.

You get a lot of bang for your buck when opening BMG’s Sabotage Super Deluxe Edition box set. The LP is newly mastered from tape and the sleeve has been reproduced in that lovely ‘linen’ texture that you get on the original pressing of Joy Division’s Unknown Pleasures. There’s a triple live album North American Tour Live ‘75 with blazing versions of ‘Supernaut’, ‘Spiral Architect’ and ‘Sabbra Cadabra’ among others. There’s a lovely extra touch in the replica/reissue of the Japanese 7” of ‘Am I Going Insane (Radio)’. There’s a replica 1975 tour poster and a nice reproduction of the tour programme which was on sale at Madison Square Gardens, with great photos (Iommi in full-on LOTR mode, Ozzy on a horse, Geezer appearing out of a hedgerow, Ward in a box car in hobo mode). Although great looking and full of fantastic photographs, the hardback 12”x12” book is the only dud in the package as the actual narrative is a rush job, constructed from press clippings, rather than written afresh, but this is, admittedly, a small grumble about an otherwise fine object helping to recontextualise an often vastly underappreciated album.