There is, in jazz, a venerable tradition of the artist-run record label, stretching back to at least the early 1950s. In 1952, bassist/composer Charles Mingus, his wife Celia and drummer Max Roach founded Debut Records, which focused on releasing music by emerging artists until it folded in 1957 – the same year Sun Ra and his business partner Alton Abraham established El Saturn records in Chicago, primarily as a vehicle for disseminating Ra’s intergalactic missives. If both of these ventures were pragmatic attempts to avoid the compromises inherent in working with major labels, they were also forthright statements of African American self-determination entirely emblematic of the Civil Rights era.

It’s little surprise that, in the midst of the political and social turbulence of the late 60s and early 70s, the idea took on a more urgent energy. In 1971, trumpeter Charles Tolliver and pianist Stanley Cowell set up the New York-based Strata-East Records, which released over 50 albums during the 1970s, including sessions by jazz heavyweights such as bassist Cecil McBee and Clifford Jordan, as well as Gil Scott-Heron’s 1974 hit album, Winter In America. Operating in the vacuum created by John Coltrane’s death in 1967, Strata-East was a beacon of Afro-centric spirituality and cultural awareness, and is now rightly famed for releasing some of the 20th century’s most powerful statements of Black American artistic identity. But it wasn’t the only label with a clenched fist in the air. In Oakland, California – birthplace of the Black Panthers – an even more revolutionary imprint was founded in 1969.

The brainchild of pianist Gene Russell, Black Jazz Records seemed, from the start, inextricably linked to the Black Power movement, with a mission “to promote the talents of young African American jazz musicians and singers” and a bold, monochromatic logo showing two strong Black hands clasped in fraternal greeting and mutual support. In a canny business move, Russell enlisted the help of classically-trained percussionist and music industry insider, Dick Schory, who had been instrumental in developing quadraphonic sound recording for vinyl LPs as well as RCA Records’ “Dynagroove” process, before founding the Chicago-based country and western label, Ovation Records. Russell arranged for Ovation to finance and distribute Black Jazz albums, leaving himself free to act as A&R and creative director.

Black Jazz released its first four albums in 1971 and amassed a catalogue of twenty records before Russell shut up shop to start a new label called Aquarican Records in 1975. After Russell’s death in 1981, Black Jazz faded out of circulation and, notwithstanding a run of CD reissues by the Japanese Snow Dog Records label starting in 2012, has remained a somewhat mythical entity. But a full run of vinyl reissues undertaken by the US-based Real Gone Music in 2020 and 2021 has changed that – providing the perfect opportunity to reassess the output of this most radical of labels.

Fittingly enough, Black Jazz’s first release was by Russell himself – a date for piano trio plus percussion suitably named New Direction, on which he covered a selection of other composers’ pieces, from the jazz standard ‘On Green Dolphin Street’ to the pop sound of Stevie Wonder’s ‘My Cherie Amour’. But it was with the label’s next salvo that it really hit its stride. A classy acoustic jazz album in the mould of Horace Silver, Coral Keys by pianist Walter Bishop Jr. featured all original compositions touching on breezy Latin vamps, strutting boogaloo, harmonically complex hard-bop and the pristine ‘Waltz For Zweetie’, with soprano saxophonist Harold Vick respectfully nodding to Coltrane’s ‘My Favourite Things’. Born in 1927, Bishop had been present at the birth of bebop in the late 40s, and was already a veteran figure by the time of his Black Jazz release. But (leaving Russell aside) his label mates were largely from a younger generation, hip to contemporary sounds from funk and free jazz to the electric jazz rock innovations of Miles Davis.

The Black Jazz roster was a diverse pantheon of undersung warriors and pioneers. Singer Kellee Patterson – formerly the first Black Miss Indiana – released Maiden Voyage in 1973, an album of gorgeous vocal interpretations of jazz compositions, including a hypnotically beautiful take on Herbie Hancock’s eponymous piece. Rudolph Johnson was a hard-blowing tenor saxophonist whose two Black Jazz releases (1971’s Spring Rain and 1973’s The Second Coming) revealed a serious minded, spiritual seeker in the tradition of John Coltrane. Bassist Henry “The Skipper” Franklin also cut two albums for the label (The Skipper in 1972 and The Skipper At Home in 1974), on which he played both upright and electric bass with a huge, ferocious bounce augmented by electric keyboard and guitar. The Awakening were a Chicago-based group with links to the Association For The Advancement Of Creative Musicians, whose albums Hear, Sense And Feel (1972) and Mirage (1973) mixed the deep, meditative vibe of Thembi-era Pharoah Sanders with the Pan-African percussion and ‘little instruments’ of The Art Ensemble Of Chicago. But, without a doubt, Black Jazz’s flagship artist was keyboardist Doug Carn.

Born in Florida in 1948, Doug Carn arrived in Los Angeles at the end of 60s, released a debut album – The Doug Carn Trio – on Savoy in 1969 and played on the first two albums by Earth, Wind And Fire in 1971. That same year, he signed to Black Jazz and went on to release four albums on the label – more than any other artist. The first three of these – Infant Eyes (1971), Spirit Of The New Land (1972) and Revelation (1973) – featured the voice of his wife, singer Jean Carn, and created an aesthetic that is now synonymous with Black Jazz: irresistibly funky yet intensely serious, rhythmically dense and propulsive yet somehow ethereal. On piano, Carn showed traces of the influence of McCoy Tyner’s heart-stopping agility and sincerity; on organ and electric keyboard he signalled his awareness of Larry Young’s work with Miles Davis and Herbie Hancock’s Mwandishi project; and on synthesizer he revealed himself to be a visionary futurist, and an early adopter of the Moog’s mind-bending possibilities.

His work as a lyricist was also crucial. Whether penning lyrics for existing compositions such as Coltrane’s ‘Acknowledgement’ or Lee Morgan’s ‘Search For The New Land’, or writing anthemic originals like ‘Revelation’ and ‘Power And Glory’, he pursued an abiding passion for matters spiritual, betraying a feeling of expectant religious awe. At the same time – and in keeping with the post-Coltrane, consciousness-raising tenor of the times – his songs simmered with an impatient call to action: on ‘Jihad’ he promised “a new day is dawning,” and on ‘Arise And Shine’ he exhorted “beautiful people arise”. While these injunctions obviously spoke of an Afrocentric urge for fulfilment and freedom, there was also the sense that he was equally concerned with the wider human family’s emancipation from material drudgery. Jean Carn’s voice provided the perfect delivery of these manifestoes of hope: simultaneously strident yet fragile, old-fashioned yet timeless, and possessed of an extraordinarily wide and slow vibrato, she sounded otherworldly, like a cosmic chanteuse from an episode of Star Trek.

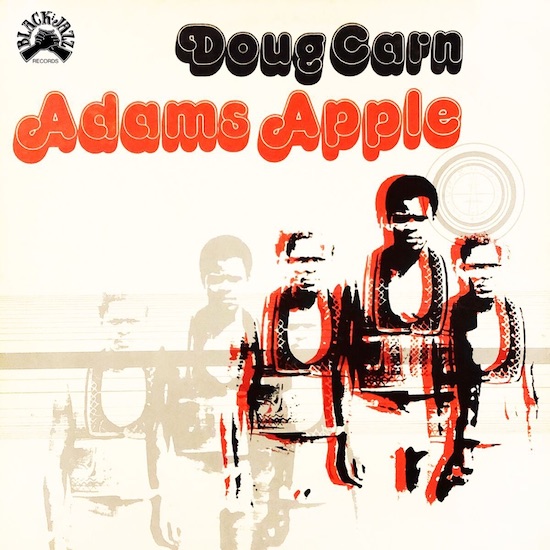

Carn’s fourth and final album for Black Jazz (and the latest in Real Gone Music’s reissue programme) was 1974’s Adam’s Apple – arguably his, and the labels’, best release. Here, the Moog synth is even more prominent, often – as on album opener, ‘Chant’, – augmenting the bassline, creating a dark, ominously determined sense of momentum, encapsulated in the lyrics: “Let’s go forward together, say a chant for the freedom of man.” Jean Carn doesn’t appear on the album; instead, vocals are performed by Joyce Greene and John Conner, credited as The Voices Of Revelation – a brilliantly apt name for their Gospel-meets-Age-of-Aquarius, apocalyptic-utopian sound. Carn’s lyrics seem even more concerned with a coming reckoning, fixated on a future-focused longing for delivery. On the deliriously funky ‘Higher Ground’ the Voices sing of building a “righteous nation”. On ‘Western Sunrise’, they proclaim “a new day is dawning.” On ‘Sweet Season’,” they joyfully welcome a new age: “Sweet season, I’m so glad you’re free to come again.”

While there are plenty of Moog-heavy, percussion-driven jams with a glowering, apocalyptic feel on Adam’s Apple, the music touches down in various stylistic territories, calling on the talents of a hard-working band including Calvin Keys on guitar and Ronnie Laws on saxophone. The title track weds a Biblical morality tale to a filthy porno-funk groove; “To A Wild Rose,” revisits Jean Carn’s orbit with a cosmic ballad akin to Sun Ra’s take on “When You Wish Upon A Star;” “The Messenger” is a fierce jazz-rock vibe with throbbing synth sirens and an urgent Hammond organ solo; “Mighty Mighty” brilliantly transforms a funk banger from Earth Wind and Fire’s 1974 album Open Our Eyes into a slice of impossibly up-tempo, insanely swinging hard-bop; and “Sanctuary” adds lyrics to Wayne Shorter’s wistful ballad, proposing an ambiguous conflation of earthly and spiritual love, with Carn murmuring a sensual spoken introduction: “Don’t run from me,” he counsels, “let me help you uncover the secret treasure of beauty and expansion that awaits our completion,” which, if nothing else, is surely one of the most strangely intense pick-up lines ever uttered.

Carn has continued to record and perform intermittently, most recently as part of Ali Shaheed Muhammad and Adrian Younge’s hiphop-influenced Jazz Is Dead project in 2020. Even so, he remains a mysterious character, somehow still brooding within the apocalyptic shadows of his early 70s obsessions. On the strength of albums like Adam’s Apple and the rest of his Black Jazz output, he is unquestionably one of the great overlooked geniuses of revolutionary, progressive jazz.