A restless cellist bought a giant fish tank. He set up his keyboard next to it, drawn to the gurgle of its filtration system. He took trips on the ferry with his Walkman, a need for horizons and depths, mirages and echoes. Not many musical perfectionists are drawn to the noise pollution of refrigerators, blenders, or ferry motors, but Arthur Russell was. He loved the hum of the drone, whatever its source. As David Toop says in 2008’s Wild Combination: A Portrait Of Arthur Russell, “Arthur was able to use this oceanic formlessness, but make his own shapes with it.”

Since his passing in 1992, the cult of Russell has almost become a micro industry unto itself. It’s easy to see why. In his lifetime only one album and string of singles were released, but his unreleased back catalogue mirrors the boundless ocean he so connected with, or the Iowa corn fields which first ignited his imagination. But reissue culture can be quite the voracious beast, subject to the same trends as contemporary music, a petulant cycle of discover-devour-discard. Russell’s importance is cemented, but perhaps due to the volume of releases, the promise of yet another unearthed trove may be met with weary indifference, a belief that the essentials must already be among us.

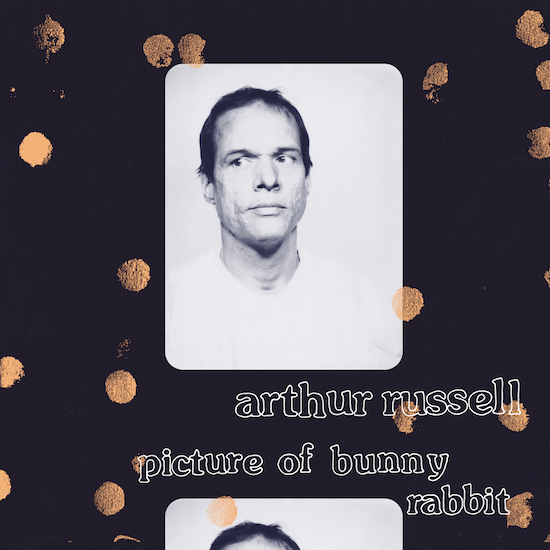

The nine songs of A Picture Of Bunny Rabbit come from the same period as his most celebrated work, 1986’s World Of Echo – the only album released in his lifetime. For those in the know, there were already many Russells by that point, and under many pseudonyms. There was the twangy singer songwriter whose earnest songs slanted the quotidian, did for folk and country what The Modern Lovers did for rock & roll. There was Dinosaur L; all sweaty loft lift-offs and pulsing limbs, where disco, funk, post punk and house fused with African polyrhythms and Indian ragas, inspired by the late night communalism of clubs like The Paradise Garage. There was the modern composer, an egalitarian who sought to erase the distinction between ‘serious’ and ‘commercial’ music, to make playful works that were open ended and open eared. These were but a few Russells.

World Of Echo contains all this, but as a Fata Morgana, conjured alone with his cello and a rig of effects. In 2005, blogger Woebot compiled his list of the hundred greatest records of all time, placing World Of Echo third, quite early into the renewed surge of interest in Russell’s work – Soul Jazz had released The World Of Arthur Russell a year prior. Woebot described the album as “disco’s bones and ectoplasm. Must, I reason, be understood as one of the only records to grapple with the horror that is AIDS. That this isn’t more widely pointed out is a crime.” This oversight has thankfully been addressed over time, though it’s certainly worth restating. Along with works like Coil’s Horse Rotorvator, Diamanda Galas’ Plague Mass and Derek Jarman’s final film Blue, it’s one of the most powerful, agonised articulations of that moment.

Russell made this music while fighting the illness, and that pain is present in the work. As is, however, a sense of utopia, not an idealised physical utopia, but through his connection with the water, a place that allowed him mental and artistic emancipation. On World Of Echo – and what we now hear on Picture Of Bunny Rabbit – Russell fully submerges himself, makes connection with the deep on the deep’s own terms, baring his soul through a language of ever more blurred refractions. Words here have no more innate, decipherable meaning than the formation of coral, the shafts of light and prismatic hues on the surfaces below, like a deep sea disco ball turning at the pace of the earth. The fragile might of Russell’s voice is not unlike that of Robert Ashley’s on Automatic Writing; clandestine murmurs, melodies like the stirring sounds of a deep sleeper, epiphanies that emerge from the inexact – this is, after all, a man who calls his tracks things like ‘Terrace Of Unintelligibility’ – as if by muddying the water we get a clearer sense of the terrain.

This was solitary work – not something he necessarily had a great deal of choice over. He could be difficult. Time spent in a commune seemed to help little with collaboration, a pursuit he’d seek out then retreat from. He had that need for complete control, was deeply paranoid about the theft of his ideas, both in his immediate circle and from groups as large as The Rolling Stones, driven to isolation by these tendencies. He received endorsement and menteeship from the likes of Phillip Glass and Allan Ginsberg, though also the tutorship of a potentially fraudulent guru in San Francisco who, according to Ginsberg, would banish him to the closet for hours on end to practise his cello. Animosity developed in the commune due to his growing obsession with music, he actually had to give up the cello in accordance with the doctrine that it was to be owned by all. This wasn’t going to work. In the same way that while growing up in Iowa, reading works by John Cage and Timothy Leary at what was judged to be a premature age, his parents found marijuana in his room, the confrontation and concern over his countercultural interests led to his move to San Francisco. Though in many ways a quiet, gentle individual, Russell had a staunch sense of what he wanted, and an inability to accept constraint in any form.

A Picture Of Bunny Rabbit may not be an obvious revelation for those already familiar with World Of Echo, but it’s as if this singular, unfathomable place has become more vast, or perhaps that new depths have been uncovered. Mere moments into ‘Fuzzbuster #10’ and we’re back there, all cello scrapes, pulsing keys and aching wail, while the picked guitar notes on ‘Fuzzbuster #6’ and ‘Fuzzbuster #9’ add a gently unfamiliar element to the equation, like a private communion being made with The Durutti Coumn’s Vini Reilly. It might seem odd that Russell’s most radical period is so bone bare, such slight embellishments, but he’s clearly working at some kind of foundational level, blurring the distinction between confessional song, Buddhist mantra, and minimalist exploration, right down at the roots. Watch him perform this material and you see a man enraptured, caught in the quiet intensity of a trance.

The title track is the least familiar thing on here, like a glitched out premonition of Oval’s 94 Diskont, any sense of formal cohesion torn apart in a manner akin to The Caretaker’s Everywhere At The End Of Time series. He’s an explorer who doesn’t want to conquer, but be humbled by his discoveries. Much of the album is song-focused, albeit borderless songs that drift between states, no verse-chorus-verse etc., Russell’s voice often subsumed, or lost in echo logic. Dylan may not seem like an obvious kindred spirit, but the two artists share an obsession with the idea of their songs as constantly evolving entities, ripe for rework, recontextualisation, or in many cases to be reshaped beyond recognition. Closer ‘In The Light Of A Miracle’ has existed in many forms, as has much of Russell’s work. You see this as a reflection of Russell, the forever displeased perfectionist, but then again in jazz, folk and blues you have the standard, so why not treat your own material in that same sense, as something malleable, unmoored and free floating.

Picture Of Bunny Rabbit warrants the fervour of those noughties compilations. We should be wary of the whims that come with obsessive discovery, the impatience of aesthetic hipsterdom. There is truly something to be said for a dose of conservation. I don’t believe that ideas or musical innovation are finite resources recklessly plundered, but outside of that, there’s also the issue that if an artist posthumously receives their flowers, we owe it to them that our appreciation is ongoing and evolving, otherwise we’re at risk of a kind of reverse vampirism. Let’s take a page from Russell’s partner Tom Lee, who has been responsible for ensuring Russell’s work endures, that so much of this unreleased material – always intended to be put out – gets to see the light of day. The pair were steadfast in their belief that music can heal, not in a corrective or prescriptive sense, but in an enrapturing sense, a harmony of interior and exterior that at its best can lift people outside of themselves, towards others and towards life.