“An ambition for us would be for people to have dreams in which our music was the soundtrack.” So said Alex Ayuli in a 1987 interview with Simon Reynolds for Melody Maker. When A.R. Kane coined the term ‘dream pop’ to describe their music (arguably the very first to do so), Ayuli and Rudy Tambala were not only beating critics to the punch and cannily labelling their product, they were sincerely engaging with a surrealist impulse to explore the subconscious, in a way that does not shy away from the elements of sexuality and violence that lurk there.

Like many children of the diaspora, Ayuli and Tambala found themselves drawn to science fiction. There is a rich tradition of Black musicians using sci-fi to construct a new identity for themselves, a utopian corrective to a present shaped by white supremacy, institutionalised racism and structural inequalities. We see this in Parliament/Funkadelic’s reimagining of old spirituals as hymns to UFOs, in Drexciya’s subaquatic techno alternate histories, in Janelle Monae’s cyberpunk calls to robot revolution. Similarly, science fiction ideas and imagery suffuse A.R. Kane’s music, from the liquid space-funk of ‘A Love From Outer Space’ to the sampling of HAL from 2001: A Space Odyssey on ‘Snow Joke’, to the music’s visceral rush towards an unimagined future. This all encourages the listener to imagine a “dreamworld”, a happier alternate world running parallel to our own. But A.R. Kane’s approach to science fiction is distinctly not utopian. In the liner notes to the 2012 Complete Singles Collection, Tambala, speaking again to Reynolds, acknowledged the influence of JG Ballard: “We used to read his books religiously. He used to mix up politics with ultra violence and sex.” As well as describing Ballard’s writing, this could just as well refer to the recurring obsessions that run through A.R. Kane’s songs, through the Lolita EP to ‘Baby Milk Snatcher’. Ballard’s writing helped revolutionise the New Wave of science fiction, by exploring taboo subjects through formally experimental prose. Similarly, A.R. Kane’s notion of dream pop embraced politics, ultra violence and sex through formally and sonically innovative experimentation. Their explorations into the oceanic or the cosmic occurs in the context of Ballard’s notion of “inner space” – their fantastical dreamscapes are reflective of a uniquely postmodern psychological headspace. As Ayuli sings on ‘Snow Joke’, “It’s just a dream, and we’re all dreaming.”

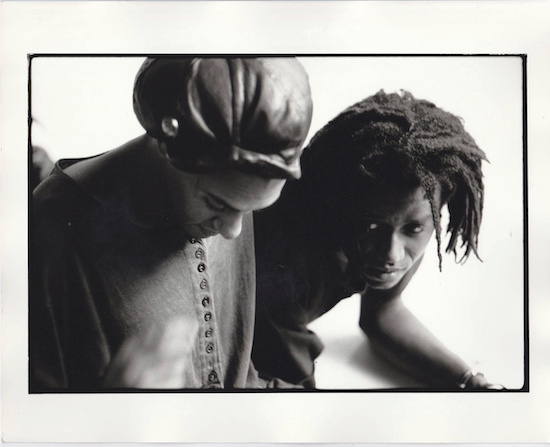

The writer Jonathan Lethem once described science fiction as being “both think-fiction and dream-fiction”. Much of A.R. Kane’s most compelling science fictional dreams are captured on the new reissue A.R. Kive, which compiles their first two albums, 69 and “i”, plus the preceding Up Home! EP, released over a remarkably productive two year period. It’s easy enough to trace back A.R. Kane’s influences – Cocteau Twins, Can and Miles Davis at their most oceanic, Sun Ra at his most spacey – and the myriad of musicians from My Bloody Valentine to Tricky to Seefeel who have drawn on them since. But what comes through most clearly, listening to these tracks, newly remastered by Tambala, is the sense of play. From their punning name, suggestive of obscure occult knowledge, to the gleeful abandon of their all-channels-open approach to music making, A.R. Kane made play central to their operations. From their cryptic lyrics to their suggestive but vague cover art, A.R. Kane approached everything like a game. The same mischievous attitude can be seen in Ayuli and Tambala’s interviews at the time.

Although they were all produced in such a narrow space of time, it makes sense to think of the two albums and the EP as distinct conceptual projects. All three releases are carefully sequenced, with a structure that implies a clear beginning, middle and end of a musical and emotional journey. And inevitably, by the time the band had moved on to the next release, the focus was new and distinct. A.R. Kane moved and developed ridiculously fast, their magpie-like attention discarding ideas as quickly as they picked them up, always grasping for the next exciting new idea.

The EP opens with the full version of ‘Baby Milk Snatcher’, the only track reprised, albeit in a shorter version, on the debut album. If their earlier releases – they’d already put out an EP with 4AD as well as their M/A/R/R/S collaboration with Colourbox which produced surprise hit ‘Pump Up The Volume’ – saw them lazily compared to the Jesus and Mary Chain in the music press, this song effortlessly showcased their originality and complexity beyond such trite comparisons. The track demonstrated that A.R. Kane had the most radical understanding of the space opened up by dub of any rock band since The Pop Group. Cavernous bass and a lilting off-beat guitar form a bed for Ayuli’s lascivious vocals, through which burst blasts of static and queasy cascades of noise. The song’s sexual imagery and its undertone of violence explicitly echoes Ballard’s sexual projection of Thatcher, as alluded to in the title. Ballard’s semi-ironic sexual fetishisation of Thatcher in an interview, and then-future President Reagan in the infamous short story ‘Why I Want To Fuck Ronald Reagan’, collected in The Atrocity Exhibition, was a comment on the politician as a media personality, packaged for the viewer’s id whilst carefully avoiding saying anything of substance. A.R. Kane’s song operates in the same hyperreal media fantasy, a dream cynically concocted to sell the public on dangerous ideologies. Ayuli’s work in advertising would have stood him in good stead to anticipate where the media age was heading. The EP’s themes continue in ‘W.O.G.S.’, the band’s angriest song. Unlike their white contemporaries on the indie scene, A.R. Kane were viscerally aware of politics, and weren’t afraid to confront the racism of 1980s Britain. “You sold me, sold me down the river,” Ayuli wistfully complains over furious guitar feedback. ‘Up’ perhaps represents the height of A.R. Kane as proto-shoegazers. The song exists halfway between a religious rapture and a science fictional journey to the stars, hope at moving on to a better world set against the sadness of leaving Earth behind. A lambent Cocteau Twins-esque guitar line is lathered in glistening feedback, over which Ayuli sings a nursery rhyme melody about leaving Earth on “a huge starbound boat”, imagining an intergalactic equivalent of Marcus Garvey’s Black Star Line.

The debut album 69 was released a mere three months after Up Home!, but already the listener gets a sense of how quickly A.R. Kane were developing. The album retains the squalls of guitar feedback, delicate guitar figures and dub-like explosions of sound from the earlier EP, but adds a more explicit jazz influence. Whereas their earlier work influenced a raft of shoegaze bands, the music on sixty nine is more aligned with Talk Talk’s Spirit Of Eden and particularly the unstable darkness of Laughing Stock, as A.R. Kane once again reached past themselves to clutch at the future. The lyrics have become even more abstract. This is an album where the music itself takes primacy, Ayuli’s vocals simply another instrument in the vast mix. With its languorous bass lines and pulsing rhythms, 69 brings to mind Miles Davis’ watery In A Silent Way, or the utopian jet-streams of Can’s Future Days. But 69 is somehow darker than both. If Future Days suggests a Jules Verne future of joyous exploration, space as the new naval frontier thanks to Can’s collapsing of the oceanic and the cosmic, 69 portentously suggests a future of astral disasters, the sounds of celestial bodies colliding and annihilating each other in songs that catalogue destructive passions and collisions of human bodies. The glorious ‘Sulliday’, which closes side one, almost sounds like a song being pulled into a black hole, as the individual elements of guitar, feedback and Ayuli’s wailing vocals about seeing angels overhead are pulled apart before collapsing in on themselves. On songs like ‘Scab’, a delirious sensuality is still the order of the day, driven past the point where pain and pleasure have any distinction. Side two is almost a continuous suite, with the delicate jazz clarinet on ‘The Sun Falls into the Sea’ a particularly striking moment. In ‘Spermwhale Trip Over’, Ayuli sings, “Here in my LSDream / Things are always what they seem,” a god caught in the bliss of an acid trip willed into reality around him. Unlike the character Ayuli sings in ‘Baby Milk Snatcher’, half in love with a seductive media image even as he senses the rot underneath, here Ayuli uses the worldbuilding power of acid-induced dreams to create a new world around him, a universe for which he is the master.

The double album “i” followed a year later, and saw A.R. Kane shift and mutate once again. Across 26 tracks, it trades the ethereal waves of distortion of its predecessor for the dance floor and an almost pop sensibility, albeit without ever losing any of their trademark eccentricity or experimentation. In contrast to 69’s surrender to collapse, “i” has some of the apocalyptic energy of Prince’s 1999, the sense that if the world is ending, we may as well face it whilst having a damn good party. ‘A Love From Outer Space’ crashes out the gates with a rolling house beat and delirious vocals, as Ayuli sings of his beloved, “Space is where we both belong,” an update of Sun Ra’s most famous mantra. It’s fitting that A.R. Kane would anticipate the bacchanalia of the ecstasy era, but being A.R. Kane, the dizzying highs are underscored with darkness; a song like ‘Crack Up’, for example, with its jittery layers of processed vocals, teeters between euphoria and a breakdown. And the HAL sample in ‘Snow Joke’ is the computer at the end of the film offering to sing to Dave as the astronaut destroys his brain. Are A.R. Kane singing for the joyous release they find in the end of the world, or are we all just mumbling to ourselves as we slide into computerised dementia, the escape promised by Up Home!’s glittering dreamworld simply a dying simulation we are all trapped in? The album works especially well on vinyl, with each side almost a mini conceptual suite in and of itself, moving from the pop brilliance of the opening side through the unalloyed lust of side two with ‘Honeysuckleswallow’ through to the guitar-led final side, which most strongly recalls the band’s earlier EPs. As such it’s almost a backwards reflection of the band’s development, charting the journey their unique musical obsessions took them on, the band ultimately retreating into the cosmic womb from which they were birthed like 2001’s Starchild in reverse.

The joy of imagining a better future is frequently frustrated by the disappointment of the future we actually get. “i” would mark the end of A.R. Kane’s golden period. It’s the last truly great flowering of Ayuli and Tambala’s creative partnership, and though the two would return in 1994 with the subdued if underrated New Clear Child, the pair of them would never create together with such wild abandon again. But across the music collected in this compilation, A.R. Kane made some of the most exciting, forward-thinking, and science fictional music of their era.

A.R. Kive (A.R. Kane 1988-1989) is released via Rocket Girl on __