The remix has always been with us. Virtually every form of folk music on earth has focused on new interpretations of old songs, to varying degrees of fidelity. The generational act of passing on music always gave rise to the possibility of development and deviation, either to improve or subvert. This was formalised in classical music in the practise of ‘variations on a theme’, where a composer would take another composer’s work and transform it. Mozart did it to Salieri, Chopin did it to Mozart, Rachmaninoff did it to Chopin, and so on. This survived into the pop music age, even before samplers became commercially available.

John Lennon overheard Yoko Ono playing Beethoven’s ‘Moonlight Sonata’ and asked her to play it backwards, turning the resulting tune into The Beatles’ song ‘Because’. Serge Gainsbourg regularly raided his repertoire of smoky late night piano bar muzak for inspiration, transforming Chopin, for instance, from a doomed Romantic into a Left Bank incubus. The prodigious output of the early Bob Dylan is partly down to his ‘remixing’ of centuries of folk tunes, from African American spirituals to Irish, English and Scottish songs collected in anthologies such as Child Ballads (and then shared by word of mouth).

The extent to which these actions were loving tributes, necessary advancements or shameless thefts is always uncertain (often, they are all of the above), and disputes inevitably follow, especially in cases when the ‘remix’ was not requested or admitted to.

Technological advances in recording in the 1970s brought us the dawn of the remix as we know it in two distinct strands, both of which were shadowed by controversy. The first was the remix as an expansion of the original, which was primarily driven by DJs who wanted more time and space to mix records together and allow people to dance. One of the first of these extended mixes was Donna Summer, Giorgio Moroder and Pete Bellotte’s ‘Je t’aime’-inspired ‘Love To Love You Baby’, which was elongated to seventeen minutes, with multiple simulated orgasms, at the request of Neal Bogart, head of Cassablanca Records who saw the libidinous effect it had on people he’d invited to an orgy at his house. He wanted a 17-minute version to play to guests the following weekend.

The second was the remix as deconstruction and rebuilding. A highpoint of this is the posthumous John Coltrane album Infinity was pieced together and given celestial overdubs by his wife the cosmic jazz harpist Alice Coltrane, which is an astonishing album, visionary at times, but it’s unclear whose album it really is. Similar issues of authenticity dogged the posthumous releases of Jimi Hendrix, particularly those like Crash Landing and Voodoo Soup (containing intriguing psychedelic doodles like ‘Captain Coconut’ and ‘New Rising Sun’ that suggest Hendrix was similarly space-bound) put together by producer Alan Douglas, who not only added overdubs but co-writing credits.

The issue here seems to be whether it is affectionate vandalism at work or cynical exploitation, but also the old Ship of Theseus problem – how much change can a work undergo before it becomes something else entirely? Before it loses its soul?

Andrew Weatherall synthesized, and excelled at, both of these two strands of remixing. He was a master at striping tracks down, finding the essence of them, and then coaxing and stretching them out so they filled dancefloors or just the inside of your headphone-wearing skull. Along the way, he’d fuck around with tracks a little, reflecting a playful iconoclasm from his punk youth. In the process he made the remix, a practise often derided as ignoble, a form of art and a joy to experience. It was ‘Loaded’, of course, that earned him fame but it was really his keen eye; he saw the beauty in that admittedly glorious Stonesy crescendo to ‘I’m Losing More Than I’ve Ever Had’ and translated it to an initially ambivalent public by exposing its layers and rebuilding it in front of them.

Weatherall was characteristically modest about his role in the success that followed, and resisted attempts by pedantic, sometimes disingenuous, music journalists to quantify who did what on Screamadelica. The poet John Keats once complained of how cold reductive "philosophy will clip an Angel’s wings / Conquer all mysteries by rule and line / Empty the haunted air, and gnomed mine — Unweave a rainbow". Or as Primal Scream and Weatherall put it more succinctly on that same album, ‘Don’t fight it, feel it’.

It’s a spirit evident throughout Heavenly Remixes 3 & 4, charting Weatherall’s long bounteous relationship with the label. The DJ had many projects, collaborations and alter-egos but there is a real sense that this music comes from the source, a wellspring that expanded into a vast fertile delta of music as his career went on. The earliest mixes are really early; the Sly & Lovechild track, for instance, was on the very first Heavenly release in 1990. As such, they bear unmistakable fingerprints of that time. The noble sentiment of the opening track (with the lyrics "All I want the world to see, togetherness and unity") nevertheless underlines the wisdom of Weatherall’s observation that “Ecstasy is a great drug but it’s also very dangerous because you find yourself on the dancefloor, punching the air to ‘Lady In Red’ by Chris de Burgh.”

Yet the same song is stylistically trailblazing, perfect for that time and, in some way, beyond it. Drifting away from the vocals, it’s a hypnotic, atmospheric Fourth World/ gospel /progressive house anthem, one that pointed the way to later songs that you could lose yourself in, with chemical assistance, to the extent that the dancefloor was no longer a dancefloor but somewhere else entirely – another continent, another planet, another life. Listening to it after a long, troubled lockdown, it is now transportive in its charming naivety and other ways we could never have dreamt back then.

There’s a paradoxical quality to Andrew Weatherall’s music, being elusive and accessible at the same time. The first two Heavenly compilations in this series featured an eclectic range of remixers from blissed-out and brooding Underworld cuts to kosmische musik channelled by Andy Votel. With records 3 and 4, the artist himself is eclectic yet singular. The tracks he reconstructs are wildly various, yet you can tell, often undefinably, that it’s a Weatherall mix. "They are always different, always the same" John Peel said of The Fall, and it’s at least partly true here.

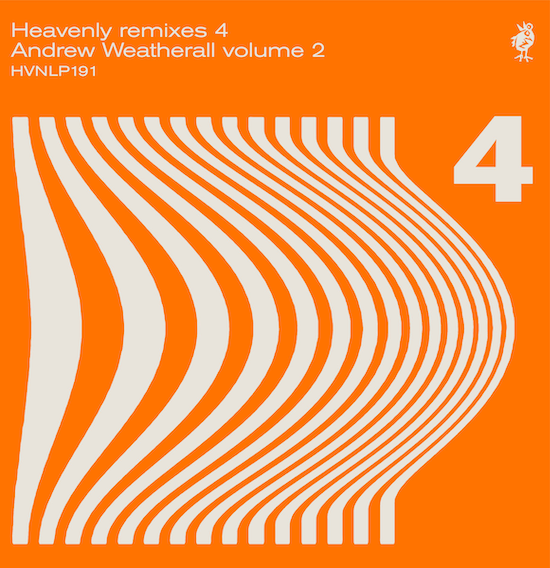

Similarly, the records should be nostalgia trips but they’re not. Instead, they are stranger than that, even the familiar remixes. Perhaps, again, it’s the disassociated time we are living in, but they feel like slightly dreamlike transmissions from elsewhere, as retrofuturist as the handsome Op Art cover.

It helps, and haunts, that Weatherall’s quality control and sonic invention never really dipped. The more recent remixes here, the airborne electro-shoegaze of ‘Chwyldro’ by Gwenno for instance, are as impressive as the recognised classics like his cinematic reinvention of Flowered Up’s ‘Weekender’. For all the variant guises Weatherall operated under and his more mercurial choices of direction, there are clear lines throughout everything he did. The sense of space and layering that he gleaned from his love of dub (as influential to him as anything from Chicago or the Balearics) echoes from beginning to end – whether the jubilant King Tubby Meets Rockers Uptown-esque first half of his famous Saint Etienne ‘Only Love Can Break Your Heart’ mix or the post-punk-saturated take on Audiobooks’ ‘Dance Your Life Away’. Weatherall never chose the obvious route, eschewing obvious hooks, instead bringing to the fore stranger quirks from the musical DNA, yet always having it underwritten with intensely compelling bass and rhythms, cavernous at times.

There is a feel rather than a formula to his remixes, which no doubt hindered him in terms of achieving the superstar DJ status that he rejected with every atom of his being anyway. Weatherall had (and it’s still strange to write about him in the past tense) the unfathomable and expansive curiosity of the true autodidact, which could lead him and his listeners to perverse places. It took this listener many years, I’m ashamed to admit, to recognise the ground-breaking genius of Two Lone Swordsmen’s Tiny Reminders, an album we have not even begun to collectively catch up with, which always seemed to be played by fellow degenerates at particularly baleful hours of near-Jacobean seshes.

Weatherall’s ability to see value in potentially everything, and to challenge musical barriers, could be perilous. On one occasion, he recalled, while being bundled out of a venue, an enraged audience making throat-slitting gestures at him because he’d played rockabilly rather than the expected pounding beats. And yet because of his self-deprecating humour and humility, referring to himself always as ‘a gentleman amateur’, such anecdotes were hilarious rather than traumatic. This provocative curiosity is imprinted in Heavenly Remixes – the dark atmospheric remix of Mark Lanegan’s ‘Beehive’, for example, is challenging but all the better for it. The well-trodden path was avoided. Even when provocative however, there was always joy, rather than cynicism, at the heart of a Weatherall mix; a joy that can be articulated not simply in mere jubilance but in an exploration of atmospherics and possibilities, always going somewhere unexpected that you did not then want to leave.

For all the joy, there is poignancy here, especially in remixes from relatively recent years. The fact that Weatherall was still at the peak of his game reminds us of what has been denied to us with his untimely death. His work was still evolving, fuelled by a move away from digital to analogue – his mix of TOY here sounds like a long-lost Neu! and Eno collaboration, his Orielle’s remix is like a merging of Gang Of Four and Chic, his Doves mix is like Blondie being thrown into the abyss. This evolution was partly due to his insatiable interest in the past, its riches and detritus, which made every interview an opportunity to talk about anything from the Albigensian Crusade to the Kindred of the Kibbo Kift. Vital too was his discerning, infectious and egalitarian ‘Have you heard this?’ quality that differentiated him from crate-digging snobs. Arguably, it was not ‘Loaded’ that set him on his path but rather his ‘Come Together’ mix on Screamadelica, with its Jesse Jackson Wattstax speech that captured a musical philosophy Weatherall came to exemplify – "Today on this program, you will hear gospel. And rhythm and blues and jazz. All those are just labels. We know that music is music."

He always remained a soul boy, for whom music was sacred but not sacrosanct, and he was an understated but passionate evangelist for it, in all its forms. "Never limit your escape routes" he used to say to any attempt to box him in. It’s wise advice. "Fail we may, sail we must" was another motto, inspired by a 21-year-old Cork fisherman called Gerard Sheehy who regaled Weatherall while driving him to a gig in Skibbereen in 2008, about the time he had skippered a vessel during a force 9 gale. What is abundantly clear in the superlative Heavenly Remixes (and his work in Sabres of Paradise, Two Lone Swordsmen et al), what is evident surveying what he left behind and what we lost with his passing, is that somehow, in the end, against all odds, Andrew Weatherall never failed.