As a music journalist, I receive a lot of emails from PRs and labels telling me about the latest releases. And, at least a couple of times a month, I’m alerted to a new album or artist being touted as spiritual jazz. In fact, it happened just this week. An email popped into my inbox raving about a “Bristolian sax and drums duo… who combine propulsive rhythms with powerful improvisation to create a uniquely heavy spiritual jazz sound". Of course, the definition of jazz is pretty elastic these days but this turned out to be a somewhat extreme example of stretching the truth: pounding, stadium-sized drums with a lugubrious tenor sax moan, swathed in a miasmic cloud of electronics. It sure didn’t sound too much like jazz.

But it also begged the question, what in the name of Lester Young’s pork pie hat was meant to be spiritual about it? Putting ill-conceived marketing gambits to one side, there’s also a wider issue to be considered here. Just what is it people think they mean when they invoke the term spiritual jazz?

For one thing, it could be argued that the phrase is entirely redundant, that all authentically-felt jazz is essentially spiritual by its very nature. Certainly, we know that it originated among oppressed and downtrodden African American communities in the late 19th and early 20th centuries as a great, roaring, uninhibited cry for freedoms both material and spiritual – and that this cry remained central to its identity and purpose in the coming decades.

Listen to the irrepressible, holy joy of unfettered self expression proclaimed by Louis Armstrong and His Hot Five in the 1920s. Dig Charlie Parker’s astonishing, superhuman virtuosity and stone cold hip persona in the late 1940s, an act of bravura self-assertion in the face of an uncaring white, straight world. Sure, Parker was peering through a narcotic haze but, even so, he was plugging into something deep, something pure, something ineffable.

Yet, you’ll rarely, if ever, hear Satchmo or Bird described as spiritual jazz. Usually the term is used to denote a certain sound that became popular in the mid-to-late 1960s: modal jazz, frequently with added eastern influences, and often with a political, Afrocentric, consciousness-raising intention. But attempts to market this as a sub-genre in its own right have merely highlighted what a nebulous concept it is. Since 2008, the British Jazzman label has, to date, released 13 compilation albums in a series simply entitled (you guessed it) Spiritual Jazz, which collects tracks mostly from the 60s and 70s, some well-known, some more obscure. Under the unifying banner “esoteric, modal and deep jazz,” releases have focused on the output of specific labels including Blue Note and Impulse!, or looked at particular regions such as Eastern Europe or Japan.

But, notwithstanding a volume devoted to jazz inspired by Islam, and a few well-placed tracks here and there (Duke Pearson’s powerful hymn ‘Christo Redentor’ on the Blue Note volume, for instance), for the most part, these selections display a notable lack of overtly spiritual content. Moreover, the cover of the Impulse! volume graphically illustrates some of the misunderstanding around the idea of spiritual jazz by carrying a vintage photo of a young black woman and a white cop locked in violent struggle, thus conflating spirituality with the Civil Rights movement and socio-cultural turmoil.

All of this confusion is kind of strange when one stops to think about the amount of jazz with a bona fide spiritual message that has actually been recorded. Take flautist Paul Horn’s 1968 album In Kashmir – Cosmic Consciousness, on which he collaborates with Indian classical musicians, and which is devoted to the Maharishi Mahesh Yogi, with a front cover showing Horn sat in devotion at the feet of the bearded, flower-garlanded sage. Or saxophonist Charles Lloyd’s 1972 album Waves, which opens with the track ‘TM’, a blissed-out paean to the Maharishi’s twice-daily Transcendental Meditation system. Consider, too, Don Cherry’s magpie, new age aesthetic, delineated with tender care on classics such as 1972’s Organic Music Society, with its big-hearted mishmash of home-grown utopian philosophy, raga-drone and the communal hippie-liturgy of ‘North Brazilian Ceremonial Hymn’. And let’s not forget Albert Ayler’s mind-blown visions of apocalyptic Christian ecstasy, communicated through mysterious titles like ‘Holy Ghost’, ‘Spirits Rejoice’, ‘Truth Is Marching In’, and Spiritual Unity.

Ayler explained: “For me the only way I can thank God for his ever-present creation is to offer him a new music impressed of a beauty which nobody had previously understood… the music we play is one long prayer, a message coming from God.”

Despite Ayler’s explicit statements of boundless religious devotion, his huge, yearning roar simply doesn’t fit with the popular conception of spiritual jazz. You’re unlikely to hear him on a Jazzman compilation any time soon. And the same goes for Mahavishnu Orchestra, too. In 1970, Yorkshire-born guitarist, and alumnus of Miles Davis’s first electric experiments, John McLaughlin, became a follower of Indian spiritual leader Sri Chinmoy and took the name Mahavishnu (Sanskrit for Great Spirit).

His 1971 acoustic album, My Goals Beyond, was dedicated to Chinmoy and featured one of the guru’s poems printed inside the gatefold. The same year, McLaughlin founded his defining project – Mahavishnu Orchestra – a power-fusion quartet whose debut, The Inner Mounting Flame, welded rock volume and excess with extended jazz improvisations and Indian scales, allowing McLaughlin to channel his burning devotion to the Lord into fret-scorching solos. He refined this approach even further with the group Shakti, in which he played acoustic guitar alongside Indian violin player L. Shankar, and percussionists Zakir Hussain and T.H. “Vikku” Vinayakram. Their self-titled 1974 debut album, which fuses jazz with both Hindustani and Carnatic musical traditions, contains probably the most joyously open-hearted track title of McLaughlin’s career, revealing the state of devotional bliss he was inhabiting at the time: ‘What Need Have I For This – What Need Have I For That – I Am Dancing At The Feet Of My Lord – All Is Bliss – All Is Bliss’.

In 1973, McLaughlin collaborated with guitarist Carlos Santana, who had also become a follower of Sri Chinmoy and received the name Devadip (Lamp, Light and Eye of God), together recording the album Love, Devotion, Surrender. A deep fug of sincerity hangs over the album like a cloud of incense smoke, with cover photographs showing the two guitarists clad all in white, walking together in hushed consultation and sat cross-legged at the feet of the haughty Chinmoy. Neither guitarist was known for musical restraint and, as with Mahavishnu Orchestra, the disciples’ depth of feeling is expressed through scorching axe-work – with the recently awakened Santana reaching states of transcendent fervour.

However, the album’s crowning achievement is a twin-guitar meditation upon a composition that sits as foundation and flaming heart of any consideration of spiritual jazz – the opening movement from John Coltrane’s A Love Supreme.

When Coltrane recorded his masterpiece of modal hard bop in December 1964, it was meant as an offering of devotion and gratitude to the Almighty, in return for helping the saxophonist end alcohol and heroin dependencies that were compromising his health and his art. Coltrane wrote in his liner notes: “In the year of 1957, I experienced, by the grace of God, a spiritual awakening, which was to lead me to a richer, fuller, more productive life." After this initial epiphany, Coltrane’s commitment to going clean wavered a few times but, by the time he recorded A Love Supreme, he was fully on track: "As time and events moved on, I entered into a phase which is contradictory to the pledge and away from the esteemed path. But thankfully now, through the merciful hand of God, I do perceive and have been fully reinformed of his omnipotence. It is truly a love supreme."

Though Coltrane was raised in the southern Christian church there was a powerful sense that his conception of God was of a universal Almighty. Moreover, in the remaining years of his life, up until his death from liver cancer in 1967, his move into more avant garde musical territory was mirrored by a growing fascination with religious traditions from around the world, from Islam to Zen Buddhism and Hinduism. His posthumously released album Om, recorded in October 1965, was a deep dive into the properties and meaning of the sacred syllable at the heart of Indian religion – what Coltrane in his liner notes called “the first vibration – that sound, that spirit, which set everything else into being."

Coltrane was such a revered and energising figure in jazz that, after his death, followers and admirers took up and championed not just his musical path but his philosophical and religious investigations too. This included famous disciples such as saxophonist Pharoah Sanders, who was a member of Coltrane’s final quintet after 1965, and whose molten tenor scream brought a heightened intensity – a kind of feral, ecstatic glossolalia – to Coltrane’s final recordings. After the master’s passing, Sanders’ own spiritual offerings became less frenzied and more reflective, as on the classic hymn, ‘The Creator Has A Masterplan’ – an undisputed, and much anthologised, classic of spiritual jazz.

But no one took these ideas further than Coltrane’s widow, pianist and harpist Alice Coltrane. Alice had been central to John’s burgeoning interest in spirituality, a catalyst and fellow seeker on the path to the Almighty. After his death, she dived headlong into the search, following Indian guru Swami Satchidananda, and releasing a string of albums that explicitly foregrounded a quest for religious meaning, from 1968’s trio date A Monastic Trio, through classics such as 1970’s Journey in Satchidananda – the title track of which, with its thick tambura drone, eternal bass vamp and cascading harp, epitomises the popular notion of spiritual jazz.

Yet, Coltrane was being inexorably drawn away from the jazz life. By the late-70s, she had moved to California, changed her name to Turiyasangitananda (The Transcendental Lord’s Highest Song of Bliss) and become spiritual director of Shanti Anantam Ashram northwest of Los Angeles, adopting the saffron robes and duties of the swamini. As the 80s dawned, her musical focus was centred entirely on the daily life of the ashram, as she arranged traditional Vedic devotional chants – or kirtans – for ceremonial use. This refined an approach that had first appeared on her 1977 album, Transcendence which reimagined ancient Sanskrit songs of praise as joyously Gospel-infused vocal call-and-response jams.

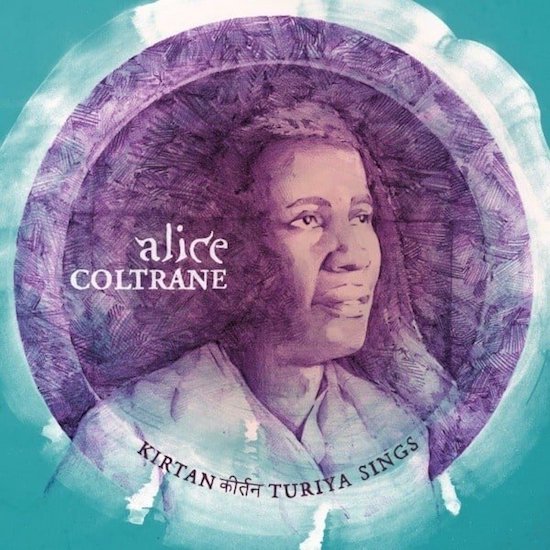

This idea reached its apogee in 1982, with the release of Turiya Sings, the first of a series of private, cassette-only releases made available solely to members of the ashram, on which Coltrane swathed her arrangements for Wurlitzer organ and voice in lush, otherworldly synthesizer and strings. It’s this astonishing album that has now been officially reissued for the first time as Kirtan: Turiya Sings – with a crucial difference. In 2004 (three years before Alice’s death) Coltrane’s son, Ravi (who has produced this reissue) unearthed a skeletal mix that stripped away the billowing synth and strings, revealing simple tracks of just Coltrane’s organ and voice. They are, quite simply, beautiful: tender, loving recitations of the names of God, both fragile and sure in their utter devotion, infused with Coltrane’s background in blues and gospel just as much as they are in the Carnatic tradition.

It’s likely you’ll hear this breath-taking album referred to as spiritual jazz. It isn’t, of course. There’s no improvisation here, no solos or showy virtuosity.

But, you know what? It doesn’t matter. Let people call it whatever they like. So long as they let its pure message of devotion and joy shine into their hearts and lift their spiritual vibrations. It’s what Alice would have wanted.