“The Caucasians wrote love-poems to their daggers, as to a mistress, and went to battle, as to a rendezvous. Fighting was life itself to these beautiful people – the most beautiful people in the world, it was said. They lived and died by the dagger. Battle-thrusts were the pulse of the race. Vengeance was their creed, violence their climate.” The Sabres of Paradise, Lesley Blanch

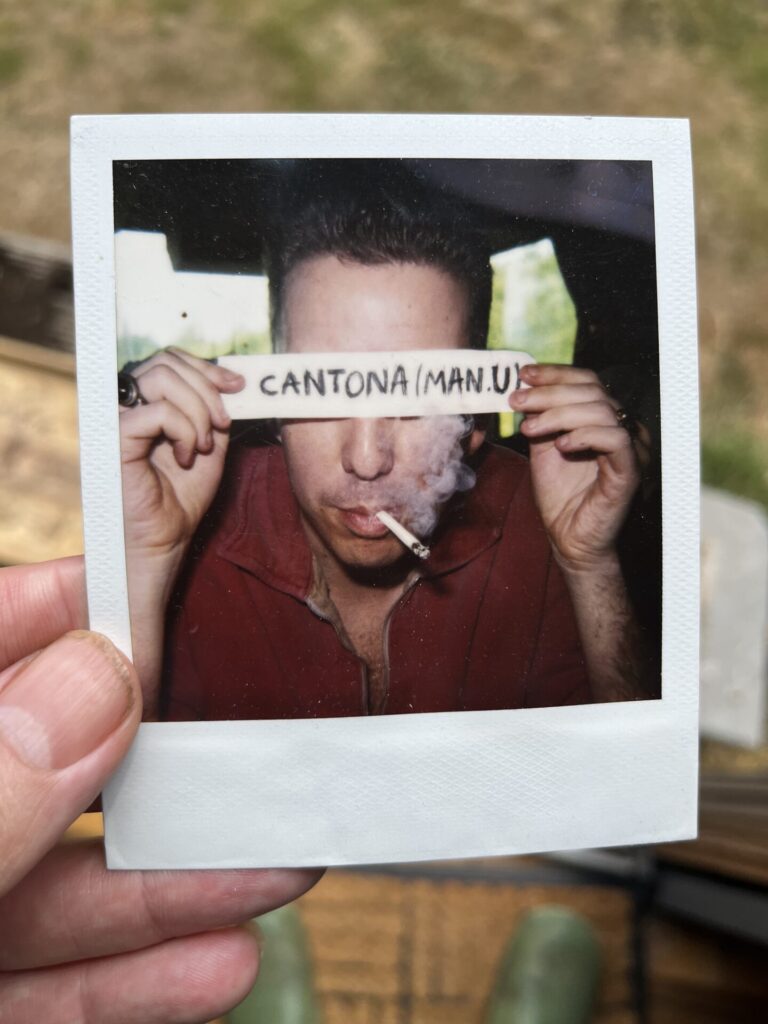

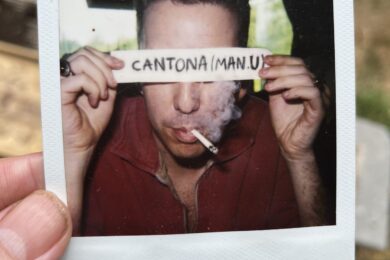

On 14 May 1994, in a crumbling Wembley Stadium, a resurgent Manchester United triumphed 4-0 over arrivistes Chelsea to secure the FA Cup. Eric Cantona, for many the defining player of the early years of the Premier League boom, scored first from the penalty spot, adding another later in the game. Flamboyant, utterly self-possessed, blessed with both otherworldly talent and a seemingly unmanageable temperament, Cantona’s controversial arrival from Leeds in November 1992 had galvanised the Class of 92, and the imperial phase of United’s dominance was assured.

On the same day, Sabres Of Paradise – the trio of Andrew Weatherall, Jagz Kooner and Gary Burns – played one of maybe only 14 gigs in their short lifetime in Leeds at Back 2 Basics. Before the show a sweepstake on the first goalscorer at Wembley was suggested by Graham Sherman, a Sabres affiliate and influential music writer responsible for spreading the early gospel of acid house. Sherman had mischievously christened Andrew Weatherall ‘Lord Sabre’ in a phone call to the Soho offices of Sabresonic – a nickname that was to define Weatherall’s aristocratic presence on the scene through the next 25 years of his epic career.

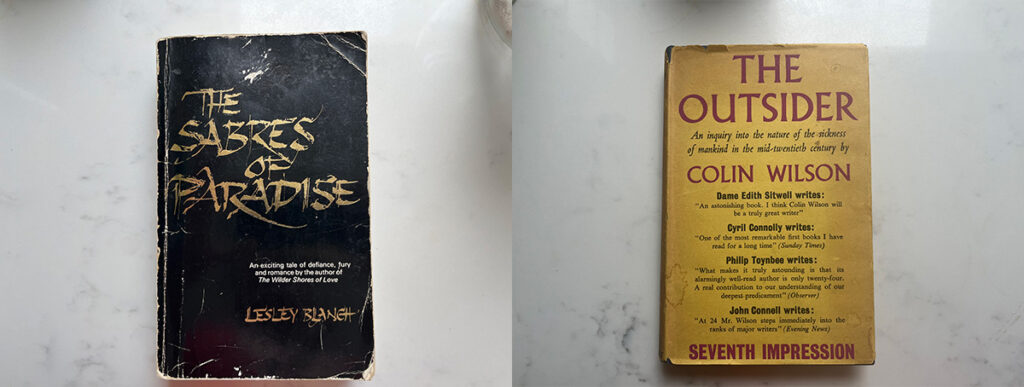

Andrew Weatherall knew a lot about everything, notably and most obviously music; but also literature, film, magic, psychedelics, biscuits, Edwardian fashions and classic British TV and comedy. What he didn’t know very much – if anything – about, was football. After he passed away in February 2020, tragically young at 56 and arguably entering his golden age of creativity, I took a phone call from Kevin Sampson. Alongside Peter Hooton and others, he’d been responsible for The End, a fanzine which celebrated football, music and casual culture. The publication was a marked influence on Boys Own, in which Weatherall dabbled in his first writing as ‘The Outsider’, a pen name inspired by his deep love of Colin Wilson.

Sampson was calling to check if Weatherall was a West Ham fan, because Liverpool were hosting them in a midweek fixture and he wanted to arrange a half-time shoutout at Anfield if so. “He definitely wasn’t a West Ham fan”, I replied. “I don’t think he supported anyone and he thought the whole ‘soccer’ thing a bit of a sham. Although he did, if pressed, express a preference for QPR, purely because he admired the hoops and thought their kit the most stylish.” You can take the boy out of Slough…

At this point in the early 90s, Andrew Weatherall – like Cantona – could seemingly do no wrong, to the extent that with no knowledge or interest whatsoever in football he won the Sabres sweepstake. As Jagz Kooner said to me, “Andrew was the fucking golden boy, because literally every record company wanted him to do Wet Wet Wet, U2 and every other fucking shit band in the world.” However, to paraphrase Dave Beer, impresario of Back 2 Basics, Andrew was always ‘two steps further than any fucker’ and would only ever pursue his own uncompromising vision. At a moment when 90s nostalgia has become a monoculture of bucket hats, pint-pots of piss and dynamic pricing, a simple Polaroid of the decade’s innovator of gnostic sonics with ‘Cantona’ stuck to his forehead speaks volumes. Here are the two great mavericks of the early 90s unified in one defiant rock & roll image: one, the footballer who was too out-there to be embraced and accommodated by his national team. The other, the artist, DJ, remix-production guru who refused to play the game, and in the process left a legacy far greater and more profound than any of his peers.

“When the truth becomes legend, print the legend.” Maxwell Scott, The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance

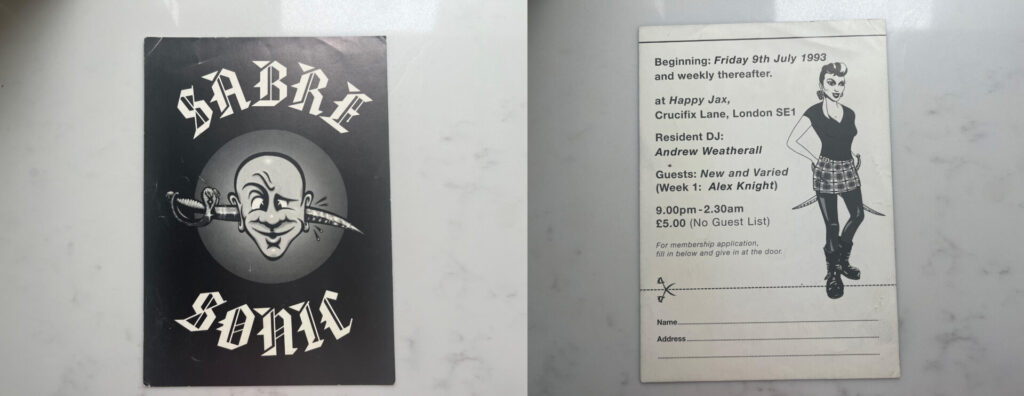

The first night of Sabresonic the club took place on 9 July 1993 at Happy Jax on Crucifix Lane, under the railway arches close to Waterloo Station. It would run for eleven months and there are plenty of full and partial appetising sets which have survived the transition from analogue to digital and now sit on Mixcloud, courtesy of those loveable lunatics at The Flightpath Estate, who have heroically unearthed and downloaded hundreds of Weatherall mixes from the most familiar and revered to obscurities. For the best part of three years, the name Andrew Weatherall had been spoken with hushed reverence both in the music press – which was then still celebrating grunge, early Britpop and shoegaze – and on underground dancefloors across the UK. But the success of Screamadelica, which both defined and haunted Weatherall throughout his life, had set him on a course of shunning further potential commercial success, at least in the short term. As the 90s became a bleak facsimile of the 60s and things began to unravel, Weatherall headed purposefully to the underground. The two albums made with Sabres Of Paradise represent his first genuinely psychedelic recordings as an artist in his own right. They mark a distinct gear change in both style and attitude; a move away from the baggy club anthems of the early 90s into a darker, more interiorised landscape that would get even deeper and bleepier in his next project, Two Lone Swordsmen.

Weatherall had unified the youth culture tribes by fusing his post punk sensibilities (later captured on his compilation Nine O’Clock Drop) and an extraordinarily catholic record collection with the Balearic tunes he had first encountered at Shoom and Boys Own parties. In the process he created something revolutionary: a sound that evolved from loved-up baggy to pared-back minimal in the space of a few years. Like Cantona he nurtured his own Class of 92 – his Gary Nevilles and David Beckhams were the likes of David Holmes, James Murphy and, perhaps most significantly, Keith Tenniswood (the other Swordsman and Radioactive Man) who was a young engineer in the studio with Sabres.

Accounts of Weatherall at the time paint a portrait of a reassuringly swashbuckling figure in leather chaps, biker boots and nose ring, every inch the Balearic pirate. He would choose to name his next major project after the book by Lesley Blanch celebrating Imam Shamyl, the prophet and warrior king who defied the Russians from his mountainous homeland of Daghestan in the early 1800s.

The precise origins of Sabres Of Paradise are unclear; stories and accounts don’t always add-up. Weatherall’s future co-pilot in ‘A Love From Outer Space’, Sean Johnston, suggests the Sabres name was actually cribbed from a track on the Haysi Fantayzee album Battle Hymns For Children Singing (1982). Whatever the truth, there’s beauty in the very fact Sabres Of Paradise was both a classic work of literature and an underground new wave obscurity. “I don’t know if it came from the record or if it came from the book,” says Jagz Kooner. Could there be anything more Andrew Weatherall than that?

W.W.A.W.D.

“What Would Andrew Weatherall Do?”

(apocryphal)

I went to see Jagz Kooner at his home in Avebury, where he has “the only recording studio in the world in a stone circle”. Kooner had been a regular at the now-legendary Full Circle club at The Greyhound in Berkshire, initially conceived as Ibiza-style chillout parties on a Sunday. He had formed The Aloof with Dean Thatcher in Uxbridge and was a Weatherall fanboy before he became a Sabre: “Literally everything he was doing was turning the world on its head,” he reflects. Instinct was always the governing impulse of Weatherall’s radar and in 1991 he suggested to Kooner they work together on the Jah Wobble’s Invaders Of The Heart track ‘Visions Of You’, featuring Sinead O’Connor. The b-side is credited with three Andrew Weatherall mixes but these were very much a collective Sabres production, as were many of the glut of ‘Andrew Weatherall’ mixes that followed. It wasn’t until a remix was commissioned by Psychic TV for ‘United’ that Sabres of Paradise were actually credited as a unit (the first release on SOP features the catalogue number and simply says, ‘Sabres of Paradise’): “I think he felt that maybe these two should be getting a bit more credit. We were fine with it”, says Kooner. “We were having a great time getting paid to be in studios, hang out with Andrew, and go to all the parties he was DJing at. It was brilliant. We didn’t really need anything else. But I think Andrew wanted to make sure these two are looked after as well. Because that’s what he was like.”

It was during the sessions booked at various studios for remix work that Sabres Of Paradise tracks started to organically come together. Often, a working day would start with a dive into Weatherall’s considerable, randomly ordered record collection. Burns, Kooner and Weatherall would pick three records blind, take them to the studio and use them for inspiration and samples. Kooner remembers this fondly as “being a bit like a comedy sketch. Sabresonic was an album of stuff that was cobbled together that we had sitting on a shelf.” Tracks were worked on in spare moments between remixes, with the demos for ‘Tow Truck’, ‘Red Stripe Dub’ and ‘Wilmot’ all done in one afternoon during sessions to make music for a Red Stripe beer ad. Weatherall, Kooner and Burns would each have eight channels on the desk. They’d press start on the computer, mute everything, lay down a bass drum, and build the arrangements live, as you might do in a band set-up. “We had this way of working which was different and unique,” Kooner explains. “It comes from the old dub reggae producers where you’d have everything muted and then bring in and add an effect to it, then mute that out and put something else in.”

Sabresonic was released on 4 October 1993, followed just over a year later by Haunted Dancehall, the more conceptually complete and coherent of the two. The second Sabres album was conceived as a narrative about ‘Nicky McGuire’, a London hood, resident in Chapel Street Market. Weatherall himself makes an appearance on the record as the ‘Duke of Earlsfield’, the London suburb where he was then living. Forays into his record collection would have yielded the 1931 calypso track, ‘Black But Sweet’ by Wilmoth Houdini, which inspired the feel and leitmotif of ‘Wilmot’, arguably the centrepiece of the album, closer in spirit to the Weatherall of the early 90s rather than the emerging iconoclast. The origins of ‘Smokebelch’, perhaps the most famous of everything in the Sabres oeuvre, are similarly easy to trace; its provenance walking a hazy line between homage and plagiarism. A cover version of LB Bad’s ‘New Age Of Faith’ which Danny Rampling used as a set opener at Shoom, Weatherall’s copy was gifted to him by Rampling himself. David Holmes’ ‘Smokebelch II’ mix, replete with insistent but melancholic rave whistles, would become the de facto mid 90s soundtrack as both set opener and the closing credits of club nights up and down the country. There was, of course, barely a dry eye in the house at Fabric when Sabres dropped this at their single UK reunion gig at the end of May earlier this year.

“If you’re not on the margins you’re taking up too much room.” – Andrew Weatherall

The 90s are now principally associated with Britpop in our cultural memory, but it is the evolution of the key electronic acts of the period as album artists that endures. Bookended by The KLF’s The White Room (1991) and Boards of Canada’s Music Has The Right to Children (1998), the range and depth and quality of releases is astonishing: The Orb’s Adventures Beyond the Ultraworld, Orbital 2 (The Brown Album), Second Toughest In The Infants, Leftism, Dead Elvis, Exit Planet Dust to name but a handful. The true character of the mid-90s was to be found in clubs like Sabresonic and Bugged Out at Sankey’s Soap in Manchester, where the original and distinct genres of house and techno were mutating into something much spacier and psychedelic, more dubbed (and blissed) out, while not necessarily slowing down the BPM count. With the benefit of rave-tinted sunglasses, Andrew Weatherall’s fingerprints are all over this, as well as so many of the releases listed above.

For many, the welcome re-releases of the two Sabres albums are a reminder of more innocent times. They echo the film soundtrack feel of many of the cosmic German artists in the 70s and anticipate the unique sound David Holmes developed on his early albums, which he worked on with Kooner. Although Sabres of Paradise will always be considered core acid house, the sound on these albums and their legacy as remixers nonpareil suggests they sit more comfortably in a psychedelic lineage than dancefloor culture. They are more King Crimson than Utah Saints. These were, and remain, ‘after-the-party’ albums, and it is the melancholic gravity and creeping industrial darkness of tracks like ‘Clock Factory’ and ‘Bubble And Slide II’ that resonate today.

Talking to both Gary Burns and Jagz Kooner it’s hard to establish why Sabres didn’t evolve and produce a third album that was slated to feature collaborations from luminaries as diverse as Tom Waits, Al Green, Ice T and Bobby Gillespie. “Andrew would not be pigeon-holed. You couldn’t hold him back,” says Kooner. “He’s going to morph and he’s going to change. He’s going to be onto the next thing and then after a while of having done that, he’s going to move on to something else. This is what Andrew was always about. You’re not going to find him trying to emulate Screamadelica for the next 30 fucking years on every album that he produces.”

Instead, Weatherall’s next move would be another two steps to the left with Keith Tenniswood and an increasingly minimal, uncategorisable and prolific run of albums with Two Lone Swordsmen. Then there’s a relentlessly uncompromising mixtape for Back 2 Basics as part of their Cut The Crap series, which for me stands as the zenith of all his DJ sets that decade. In hindsight, Sabres Of Paradise feels like a bridge between the Balearic early Weatherall mixes and his late 90s incarnation in Shoreditch at the legendary Scrutton Street studio as he increasingly favoured a life out of the spotlight.

I remember a conversation with Weatherall at our last Convenanza Festival together in September 2019. He told me about Dave Stewart and how he suffered from ‘paradise syndrome’: a condition in which a person suffers a feeling of dissatisfaction despite having achieved all of their dreams. “Strangely enough, that’s never been a problem for me”, he said, as he drew on one of the many hash spliffs that punctuated his day.

With thanks to Graham Sherman for visuals, Tim Murray, Matthew Jones, Gary Burns and Jagz Kooner. Sabresonic and Haunted Dancehall are reissued by Warp on 1 August 2025, more info here. Preorder The Sounds from the Flightpath Estate Volume 2 (Golden Lion Sounds) here – all profits from this record go to causes close to Andrew Weatherall’s heart