How much do the wishes of artists weigh? It might seem a strange question, given the adulation that exists around certain stars, but perhaps it’s more of a grey area than we might suppose. We only know of Franz Kafka, a colossal figure in literature, because his friend Max Brod went against his wishes and refused to burn his manuscripts after his death. Our appreciation of the life and work of Vincent Van Gogh owes a great deal to the publication of his private letters to his brother Theo, after their untimely deaths. Did Vivian Maier want to end up famous, with the thousands of remarkable photographs she took, quietly and for herself, going viral after they were taken from her hands? Would Kurt Cobain, composer of ‘Radio Friendly Unit Shifter’, have been comfortable with his journals and homemade cassettes being exposed to the public gaze and critical scrutiny? How many diaries have been published? How many demos are tacked onto albums now? How many archives delved into once their guardians are out of the way? Perhaps artists are too close to recognise their own lost gems. And perhaps we are, justifiably or not, graverobbers.

Radiohead have rarely been comfortable with the visibility of fame or its more absurd quasi-religious qualities. They are protected, to some degree, by the wealth and influence success has brought, meaning they can largely afford to do things their own way. Their career and reputation would not be damaged, the way an up-and-coming group or artist’s trajectory might, by the theft of unreleased material. Initially reported as a case of bootlegging blackmail (it seems more complex and convoluted now), the band decided to release their minidisc recordings made during the recording of OK Computer to head off unauthorised leaks. Proceeds will go to Extinction Rebellion. Yet the process must have felt like an affront to a group who clearly approach their work and their image with meticulous thought and care.

Whether or not, we should listen to the recordings tells us something of how we now consume content; two words that also tell us something of our age. Zeitgeist, with its ghostly connotations, is a term that seems to cling to OK Computer, perhaps more in hindsight than back then. Giving in to temptation, with the excuse that it was now out in the world anyways, I decided to listen to the material in its entirety, walking around the woods in the rain, as befits the subject. It was an undoubted intrusion but revelatory as intrusions tend to be. At times, it sounds the way OK Computer looks; that Stanley Donwood cover that he described, to Rolling Stone, as “a kind of fog world.” Opaque. Fragmented. Full of relics and junk. The sound of people in transit. Intercoms, cartoon babble, birdsong, Czech public transport, beatboxing, and Stockhausen. The buzz of a fridge. A nebula of stuff.

The first time I heard OK Computer a month after it came out. It was a summer album, lest we forget. We’d escaped across the border to Donegal to camp and drink and breathe freely away from violence and division that was emanating from the Drumcree debacle. My mate played it on a tape player that would gradually slow down as the batteries ran out. It sounded like a fascinating mess, serene in places and agitated at others, which reflected the times and our states of mind. It took several listens though to even begin to get a hold on it, especially given the opening salvo of ‘Airbag’ and ‘Paranoid Android’. Listening to the materials it was constructed from now, twenty odd years later, I realise how precise and polished it actually was. For sure, the structures of and the effects used on the songs were unconventional and the themes were disconcerting; a Baudrillard-meets-Hitchcock mix of dislocation and anxieties; the world, at once unreal and threatening, simultaneously hurtling by and closing in. The minidisc recordings reveal a long process of refinement. There are certainly moments of inspiration that fall out of the ether or were encouraged by disruptions but there’s also an unromantic revealing of how much of a slog it must be to create such an album. Interminable repetitions, bumbling, revisions, excisions, increments, failed experiments and blind alleys that would dissuade all but the most fanatical completists.

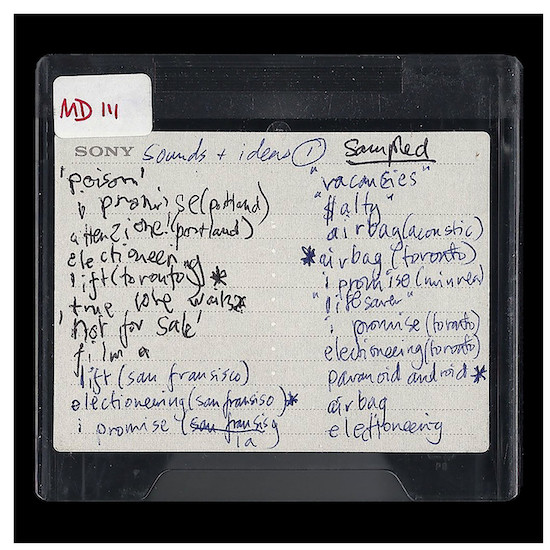

Small wonders are waiting to be uncovered here, though they take considerable searching. While there’s limited novelty these days in live performances, given their ubiquity online, there are a few stunning examples scattered in the tapes. It’s Yorke’s demos that immediately stand out however. There is an enticing solo variation of ‘Last Flowers’ on disc 6, though a later full-band version overwhelms a fragile overlooked beauty of a song. An exquisite fingerpicked ‘Exit Music (For a Film)’ (disc 11) also introduces another song, more distant in the future to come, ‘Life in a Glasshouse’; showing how songs can evolve and divide (a zygote of ‘Little by Little’ appears elsewhere). The instrumental backing to ‘Fitter Happier’ (disc 9) sounds unexpectedly poignant and ethereal shorn of its robotic lyrics, like a piano in a darkened dusty attic. Perhaps the best moments come with Yorke’s impromptu and intimate a capella versions of the B-side ‘A Reminder’ (disc 18) enveloped in the wind.

Lyrically, the recordings highlight certain aspects of Yorke’s writing. Understandably, he often sings in nonsensical mumbles (or non-lexical vocables as they’re known) that fit the rhythms as the songs take shape. When comprehensible, different tones are revealed, changing the sentiments of familiar songs. The aforementioned solo ‘Exit Music’ is less Romeo and Juliet and more Jekyll and Hyde, “Get… get away. I’m no good, I am poison. Leave me be.” Unease and yearning come hand in hand. In an alternate version of the otherwise-antisocial ‘Paranoid Android’, Yorke sings, “I watch you sleeping, and I want to sleep like you.” His talent for recontextualising stock phrases and glimpses into everyday life is often overlooked, as is the gallows humour in his lyrics (“That’s it, sir, you’re leaving”). Like Samuel Beckett, the cliché that Radiohead are grim and depressing is contradicted by the fact that dig down a layer and there’s a rich vein of black comedy (keep digging though, in the case of both, and the abyss beckons). Though idiosyncratic, Yorke seems to have learned from Tom Wait’s ability to take a fragment of a nursery rhyme and turn it into something menacing or wondrous, just as Yorke learned from Michael Stipe that it’s much more effective to build up lyrics impressionistically in collage rather than telling direct linear stories. In this sense, the lyrics of OK Computer (from voodoo economics to air crashes to hearts full up like landfills) match the cover art; the indistinct but recognisable confusion of the late capitalist neo-Waste Land. By the time we reach an adaptation of ‘Climbing Up the Walls’ (disc 10), the dark heart of OK Computer where the modern furies themselves speak, read in an eerie slowed-down fashion by Dan Clements and sounding somewhere between a narcoleptic cartoon character and Throbbing Gristle’s ‘Hamburger Lady’, it’s unclear whether we should laugh or cower in terror.

For the most part, the discs are the sound of the album gestating. There are experimental sounds that appear like intros to songs that never arrive. There are repeated piano motifs with drum loops that suggest exploration but seem trapped in the time. At times, the band are fishing for a melody or direction. An intriguing take on ‘True Love Waits’ (disc 10) bubbles up with a surprisingly slinky bass, keyboard arpeggios and almost a breakbeat. On disc 4, it appears in instrumental form like the theme tune to a tiny lovesick robot. Neither really work but both show that the song was worth returning to and also that Radiohead have never really nailed it. It has always been utterly enchanting and elusive, like a half-remembered dream.

Somewhere along the line, perhaps in the completion of ‘Exit Music’ or ‘No Surprises’, Radiohead seem to have mastered the power of restraint. Having had his vocal range liberated by listening to Jeff Buckley, by his admission, Yorke came to understand the importance of control, as shown masterfully in ‘Nude’ (or musically in the delicate build/dissonance/harmonic release in ‘How to Disappear Completely’). Often though in the demos, Yorke’s vocal approach borders on the overwrought. At moments where he sings of “freedom from depression”, for instance, the demos feel almost prurient and we are unwelcome voyeurs listening in (which we are). Of the unreleased untitled demo tracks, not many are memorable enough to rank even alongside Radiohead’s B-sides at the time, though disc 2’s sleepy “If I ever get my head out of this…” track is pleasing in almost a Shins way. Disc 17’s “Everybody wants you but nobody wants you…” track, vaguely reminiscent of a muted downbeat ‘Nightswimming’ by tour-mates and mentors R.E.M., also has its charms. The many versions of ‘I Promise’ indicate not necessarily confidence in the song but a subliminal lack thereof and an unwillingness by the band to let it go. They chose correctly in the end. Reportedly leaving ‘Lift’ off OK Computer because they thought it would be a hit seems a sign of emerging maturity rather than petulance as might be interpreted, given its buoyance would’ve unbalanced an album that, in its cracked way, builds towards the crescendos of ‘Lucky’ (with ‘The Tourist’ as a glacial epilogue).

There are signs all through the recordings of another Radiohead, belonging to a parallel world where they continued to be the band of The Bends or even Pablo Honey. OK Computer’s classic status belies the fact it is a transitional album and things could’ve been so much different, if they’d remained the same. A warm blissed-out version of ‘Airbag’ (disc 1) could’ve begun The Bends II but they chose to escape the diving bell to somewhere more adventurous, mainly by bolstering the track with DJ Shadow-inspired beats and discordant sounds. In a short-term sense, it would’ve been an easy move but they took risks. The minidisc recordings are at their worst when they fail to do this and instead display the kind of brash confidence a band exhibits when it isn’t really confident about the material – snarky vocals, screeching guitars, well-trodden post-grunge rhythms. An unreleased track near the end of the second disk suggests there was still a tempting mine of the ‘Anyone Can Play Guitar’/‘Pop is Dead’ indie rock that hadn’t yet been depleted or shut down. It was clearly something of a comfort zone for the band. It’s a testament to Radiohead that no such retreats ended up on OK Computer, which retained relatively coherent song structures but put them under considerable duress. It also shows that Kid A was not just a Warp records-inspired leftfield lurch, it was also a final exorcism.

There are moments however where the band depart from their comfort zone and, unfortunately, from the listener’s. It’s intriguing, but not necessarily pleasant, to hear them being uncharacteristic at times such as the Winwood-esque organ on disc 3’s take on ‘Nude’ or the ELP-style ending to ‘Paranoid Android’ on disc 12 (there’s no shortage of wig-outs in these tapes). You realise how judicious Radiohead’s focus normally is when they are unfocused. Bluesy licks are not their forte and a sojourn into RHCP-style funk on disc 7 sends a shiver down the spine (at one point, a comparison is made to ‘Station to Station’ but a train-wreck between stations is more accurate). On disc 10, the “I don’t want to hurt you” track falls somewhere between Mazzy Star and Nirvana but oddly listless with it. An early take on ‘The National Anthem’ entitled ‘Everyone’ is less of a dark kosmische musik groove and more of an abortive attempt at Nine Inch Nails, minus the under-acknowledged minimalist dance element Reznor developed from Prince.

The world has changed since these recordings were made. Managerial-speak, for one thing, has become more knowing and in on the joke. The “job that slowly kills you” will not last until your death; you’ll need to have a multitude of them. “The yuppies networking” don’t look like yuppies anymore. They like all the right things now. The sense, or reality, of living precariously has deepened to the extent that the damning lyrics of ‘Fitter Happier’ sound strangely aspirational now. Maybe there’s a hint of nostalgia listening back to OK Computer, angst and doom-laden as it is, because it was made in a younger world but we’re living the results of then, just as the way we hear the album, and these outtakes, is partly a result of now. The conditions are impossible to separate. While having no shortage of ignorance, we do have a shortage of mystery in our data-saturated clock-tormented present. In the future we’ve reached, everything is redundant within fifteen minutes.

Radiohead seem an exception, for Generation X at least, maybe because they are still going, still producing superlative work, and yet are connected like an umbilical cord back to a formative time before the explosion of the internet. The themes of OK Computer still abound, even more so – political machinations, technological disembodiment, speed and inertia, the fracturing of certainty, all manner of phobias, and self-destruction, that “handshake of carbon monoxide” reaching from the past towards us. Above all, there is the theme of fragmentation itself.

Reviewing these recordings may be superfluous. The songs were not designed to be heard but to be worked through and altered so it’s akin to reviewing storyboards or rushes. The semi-legendary extended cut of ‘Paranoid Android’ will no doubt be underwhelming in reality (Paul McCartney should definitely keep ‘Carnival of Light’ locked away and let it remain infinite in Beatles fans’ imaginations). It also depends how much we value artists’ intentions and where artists are placed in our culture. On one hand, the access and information we have now has, rightly, deflated the idea of musicians being saints, or demons, to be worshipped on a pantheon with their work treated as reliquaries. On the other, the way we consume music (and consumerism has had a deep influence on who we all are now in ways we are loathe to consider) has meant they are the producers of disposable content in a climate of instant gratification for an insatiable audience that want everything, except what they might need. One of these absent things is mystery.

Listening to these recordings, for all the flaws and treasures within, I found myself remembering that scene in The Wizard of Oz where Toto reveals the great and powerful Oz as merely human, “Pay no attention to that man behind the curtain.” You can look at it politically, and psychologically, like the stripping away of the Spectacle and the unveiling of the mighty as fallible and dictatorial. Yet there’s also a sense, in creative terms rather than political, of the importance of that masquerade, for our sake if not the artists. A sense that there are places where we should fear to tread if we wish to retain a sense of value, mystery and wonder. The curtain exists, perhaps, not just for the benefit of the person behind it but also for those of us outside it.