"I was intrigued by the scales, initially, and obviously the vocal work. The way she sang, the way she could hold a note, you could feel the tension, you could tell that everybody, the whole orchestra, would hold a note until she wanted to change."

Robert Plant in The Independent

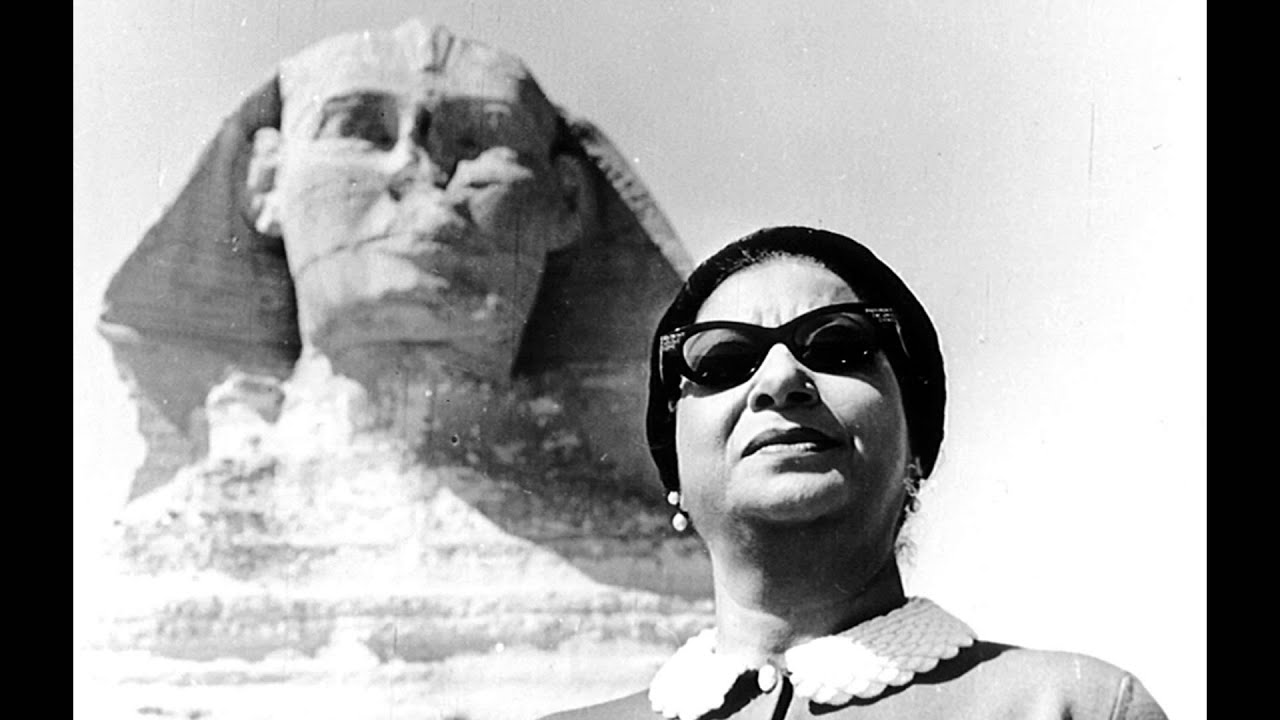

Umm Kulthum was a one-off. She was a diva in the truest sense, but at the same time she was an original working-class hero who repeatedly identified herself as a villager, a fallahah or peasant, who shared a cultural background and essential values with the majority of the Egyptian populace. To say Kulthum was an iconic figure in Egypt would be to do the term iconic too gross an injustice. Commonly known as Kawkab al-Sharq (The Star Of The East), Umm Kulthum was so much more. She is almost regarded as royalty in Egypt and the wider Middle East; and she also held the sort of power normally reserved for presidents and heads of state. For example, she died in 1975 but to this day at 10pm on the first Thursday of every month, all Egyptian radio stations play nothing but her music.

But this is not the only way she makes her presence felt. Get into any taxi in Cairo and there’s a pretty high chance the driver will be playing one of her songs. Late at night grainy black and white footage of her live performances will be screened on the TVs of countless bustling street cafes and shops. Then there are images, portraits, murals of her as street graffiti, not to mention the millions of cassettes and CDs stocked in small kiosks, which relay her art throughout the Middle East.

Umm Kulthum was born Fatima Ibrahim al-Baltagi in a rural village called Tammay al-Zahayrah near the city of al-Sinbillawayn in the Delta province of Daqahliyah, to father al-Shaykh Ibrahim al-Sayyid al-Baltaji, who was an imam at the village mosque and housewife mother, Fatmah al-Maliji. There’s no certainty as to her date of birth, but the most reliable suggestion is May 4 1904 according to provincial birth records. The family dwelled in a small mud brick house and lived in near-poverty. The family’s meager source of income came from her father by singing religious songs for weddings and other celebrations in his own and neighbouring villages.

Umm Kulthum described her modest upbringing: "It was a humble village. The highest building in it did not exceed two stories. The greatest display of wealth was the Oumdah’s carriage pulled by one horse! And there was only one street in the whole village wide enough for the Oumdah’s carriage. I sang in the neighbouring villages, all of which were small. I thought that the city of al-Sinbillawayn was the biggest city in the world and I used to listen to news about it the same way one would listen now to news about New York or London or Paris."

She learned to sing from her father and at a young age showed exceptional talent for the art form. He also taught her to recite the Quran, and it’s said she memorized the book by heart. She also overheard her father teaching songs to her brother Khalid, who was supposed to accompany him at the celebrations that he sang at. When Ibrahim discovered what she had learned and heard the unusual strength of her vocals, he asked her to join the lessons. Kulthum began performing at the age of twelve, when her father disguised her as a boy so she could be part of his troupe.

She later moved to Cairo in 1923 with the aid of the musical mashayaikh (religious imams and muftis) from al-Sinbillawayn. It wasn’t long before her voice was identified as being exceptionally strong by musical experts and she quickly found work via theatre agents. Despite her exceptional talent, there were some concerns that her voice was perceived as untrained. She lacked command of vocal nuances and subtleties that some of the established singers of the day had in abundance.

But she had a contralto vocal range. She could sing as low as the 2nd octave and had the ability to sing as high as the 8th octave at her vocal peak. Her vocal strength was unparalleled and apparently no mic could withstand this, forcing her to stand at least one metre away from it when she sang. In other words, she had a serious set of lungs on her.

With regards to her lyrical style, she sang songs that were, for the most part, poignant and reflected upon lost or unrequited love. But she also produced a fair amount of religious songs due in large part to her upbringing. However there were exceptions to these rules, and one such example was ‘Hadith el Rouh’ (‘The Talk Of The Soul’), which was recorded after Egypt had been defeated in the Six Day War by Israel in 1967. This conflict left many Egyptians in a state of anxiety; worrying about the future of their country. A widely believed story about one of her concerts, has it that many army generals who were in the audience during a live performance of this song were reduced to tears.

During the 1920s and 30s, Umm Kulthum began to realise the power of the mass media; and this became a tool which would prove essential to her endurance, longevity and popularity. Her commitments included broadcasts, from the inception of Egyptian National Radio in 1934, to feature films and then finally television in 1960. These performances only led to an ever increasing popularity with regular Egyptians and eventually led to the tradition of her concerts being performed and broadcast on the first Thursday of each month during her musical season (which lasted from October to June). At this time, Umm Kulthum’s songs were virtuosic, as they befitted her newly trained and very capable voice. They were romantic and modern in musical style, feeding the prevailing currents in Egyptian popular culture of the time.

The 1940s and 50s are seen as being the singer’s golden age. Such was her growing popularity and acclaim, King Farouk requested private concerts and even attended her public performances. In fact such was his love for her music; in 1944 he decorated her with the highest level of honour he could, the Nishan al-Kamal (Order Of The Virtues). This award was otherwise exclusively awarded to members of the royal family and politicians.

Despite this recognition, the royal family rigidly opposed her potential marriage to the King’s uncle, a rejection that deeply wounded her pride and caused her to distance herself from the royal family and embrace grassroots Egyptian causes. Among the causes she dedicated herself to was helping the figures who would go on to lead the bloodless revolution of July 23 1952; prominent among them, the soon-to-be president of Egypt, Gamal Abdel Nasser.

Some claim that Umm Kulthum’s popularity helped Nasser’s political agenda. For example, the President understood that her power and influence over Egypt was such that even the royal family and upper echelons of the army could change just on her say so. Even political votes couldn’t coincide with her concerts for fear of upsetting the populace. With this in mind, Nasser’s speeches and other government messages were frequently broadcast immediately after her monthly radio concerts. Her songs also began to take a new turn musically. Because of newer republican trends and popular tastes shifting, her oeuvre became more nationalistic.

While her character was perceived as being dominant, she was actually quite a vulnerable person. On at least one occasion, the author Mustafa Amin was said to have entered her room to find her sitting down crying alone. The reason for this is unknown, but it does hint at a more troubled side to her personality. And then there are some outlandish stories attached to her emotionally resonant talent, such as her "habit" of gulping down lung bursting draws of hashish before each performance and wearing a shawl steeped in opium from which she would inhale during concerts. Whether these rumours have any grounding in fact or not is open to discussion, but those who support the idea that she was a regular user of narcotics, question how she was able to sing so passionately for such long durations. A typical concert might contain only three or four songs but last several hours, with one song often lasting the duration of one hour; featuring one line or verse repeated over and over again. Some critics have been guilty of reverse sublimating the resonant longing in her songs away from unrequited love and onto narcotics instead.

Throughout her life, she was plagued with a host of health problems that began in the 30s. She became ill because of liver and gall bladder problems in the summer of 1937. The following summer Kalthoum spent a month recuperating in Vichy and returned to Egypt feeling better, although she was, from then on, bound by the limitations of a strict diet prohibiting most kinds of food and related problems afflicted her throughout her life.

On January 21 1975 she nearly died because of severe problems with her kidneys but despite years of medical treatment, she resisted hospitalisation, saying, "If I go to the hospital, I’ll die there." She died a couple of weeks later from heart failure on February 3 1975. Her funeral was to be held at the Umar Makram mosque in central Cairo, the site of most funerals for well-known Muslims in the city but crowds of grief-stricken Cairenes – an estimated two to four million people – far exceeded the number anticipated and literally filled the streets of Cairo bringing gridlock, so the funeral did not proceed as planned.

Her popularity is by no means restricted to Egypt. According to Egyptian music experts David Lodge and Bill Badley, Israeli radio stations still try and seduce Palestinian listeners by playing her music, mixed in with propaganda. It’s worth noting that Umm Kulthum has an immense popularity in Israel among Jews and Arabs alike, and her records continue to sell about a million copies a year.

Comparing Western music to Egyptian music (for example, to compare Umm Kulthum to Elvis or The Beatles as a point of reference) is to grossly understate her popularity and importance in the Middle East. Umm Kulthum’s unchallenged dominance of Egypt and the Middle East’s recent cultural history and association to this day remains just that – unchallenged. 40 years after her death, she lives on in the hearts of many with her songs – an artistic wealth that passes down from generation to generation.

Umm Kulthum: A Personal Top Ten

‘Enta Omry’ (You Are My Life)

‘Enta Omry’ is a song in a slow, mawal-style about the yearning for one’s desire. This particular performance was recorded at the Olympia Paris, 1967. It was one of the only shows she performed outside of the Middle East. She spent some time in France where she had a lot of admirers, such as Charles De Gaulle who referred to her as "The Lady".

‘Tala’al Badru Alayna’ (The Full Moon Rose Over Us)

‘Tala’al Badru Alayna’ is a traditional Islamic nasheed sang to the Prophet Muhammad (PBUH) from his followers upon his arrival at Yathrib, after completing the Hijra from Mecca to Medina. It’s also a song that is 1400 years old, therefore making it one of the oldest in Islamic culture. Some conservative Muslims see Umm Kalthoum’s version as controversial because it contains musical instruments, which is sometimes frowned upon in the performance of devotional song.

‘Elf Layla Wa Layla’ (1001 Nights)

In a sense, ‘Elf Layla Wa Layla’ is a pretty unusual song for Umm Kulyhum as it’s quite a tender song lyrically. It’s not so much about a love lost, but rather about being in the midst of falling in love. The opening lines, "My sweetheart, my sweetheart, my sweetheart/The night and its sky, the stars and its moon are keeping me awake all night", are pretty evident of this.

‘Baeed Annak’ (Far Away From You)

Another performance recorded at the Olympia, Paris in 1967 and yet again, another song of longing; detailing how she has forgotten to sleep, forgotten about day and night and is yearning for her love by falling into a stupor. The absence of the one she desires tortures her and you almost believe the words coming out of Kalthoum’s mouth, such is the strength of her mawal, as though this were really happening, rather than just being the lyrics to a song.

‘Fakarouni’ (They Reminded Me)

This track was written by the legendary singer-songwriter Mohammed Abdel Wahab and has yet more lyrics about yearning. But this time, the subject is someone from a past relationship. The opening lines are pretty evident of this: "They told me again about you/they reminded me/they awoke the fire of love in my heart and in my eyes/The past returned to me with its sweetness, its richness, its torture, its offense."

‘Al-Atlal’ (The Ruins)

This song is one of the most complicated and esoteric works of modern Arabic music and poetry. It’s also Umm Kulthum at her most vulnerable. Here she talks about the ruins of a relationship and about how she tried so hard to make the marriage work but ultimately how, in her words, she wants to given her freedom. While this song is around an hour in length, it’s a little slow to start off with. Her backing orchestra sets the scene with a stirring string section. After about five minutes or so, Kalthoum rises to her feet in one of her famous gowns – shawl clutched in hand – and sings in her customary multi-octave style to a packed audience, who lap up every word.

‘Ya Leil Al Eid’ (Oh Night Of Eid)

This is another religious song and this time, celebrating the night of Eid. This is a performance at the peak of her powers in 1944. As you’d probably expect, this is a joyous tune, in keeping with the festival celebrating the end of the month of Ramadan and the beginning of the celebration (Eid means holiday/celebration) that follows. The song centres on the concept of delight, togetherness or a friendly atmosphere. What’s really interesting is the last verse when the joy is transposed to a nationalistic setting, citing: "Oh Nile, your waters are sweet/You spread light throughout the fields/May you live long and prosper/oh Nile/And enjoy many Nights of Eid."

‘Shams Al-Aseel’ (The Setting Sun)

It is said that when Umm Kalthoum was lying on her deathbed in 1975, she wanted to hear this ode to the River Nile as song as she passed on. ‘Shams el-Aseel’ was a fitting song, for Kulthum had always been labelled as Al-Asil (the Authentic) because of her penchant for pure classical based music, rather than utilising Western melodies.

‘El Hob Kolo’ (All My Love)

An edited four minute version of ‘El Hob Kolo’, where Umm Kulthum sings about opening her heart to love, but longs for the times where "all the love I loved was yours/All my love/And all my time I lived for you/All my time." It is in essence a standard Kalthoum track, in terms of subject matter – with the longing of her desire seemingly never ending.

‘Wa Daret Al Ayam’ (The Days Went By)

This particular performance is from a concert in Abu Dhabi.