The 1960s and 70s were a period of flourishing for Yugoslavia’s Roma people. Even as Tito filled prison camps off the Adriatic coast, at home the Roma enjoyed official recognition for the first time. In a campaign for political stability, Tito conferred on Yugoslavs the right to identify according to their group, and the Roma – historically persecuted and mere decades earlier murdered in the tens of thousands by the Ustaše fascists – were amongst the main beneficiaries. Roma culture was suddenly pushed overground.

The music of that period has been captured in a new collection of pop and folk made between 1964 and 1980 by the Roma of Macedonia, Kosovo, and southern Serbia. Stand Up, People is an extraordinary set of tracks that demonstrate the pioneering spirit of the period, in which musicians took traditional forms and tilted them restlessly towards modernity. The songs pulse with the familiar tropes of Slavic folk music, but they are pitted against the vast breadth of new styles to which these communities were exposed. The collection is shot through with Western pop, psychedelia, and the subcontinental traditions from which the Roma originated and with which exchange was rife, thanks to India and Yugoslavia’s common position as non-aligned states. The result is a vertiginous flight of melancholic innovation.

Curated by Londoners Philip Knox and Nat Morris, Stand Up, People is the result of months of digging through Balkan flea markets, in an attempt to throw new light on what Knox describes as "something that had been missed by the standard narrative of music in that part of the world." In classic reissue tradition the record is complemented by exhaustive liner notes including, delightfully, the lyrics to each of the tracks. In translation the combination of lachrymosity and celebration so palpable in the delivery is rendered even starker. This doleful revelry is the collection’s signal quality.

The Roma renaissance abruptly collapsed after Tito’s death. Its proponents were either subsumed into the national music of the new states that were later birthed so bloodily, or simply vanished from the public eye. Romani traditions became private affairs once again, divorced from the mainstream in which they had briefly flourished. Roma remain the subject of quotidian persecution around the world. Stand Up, People is therefore important not only as a historical document but as a rejoinder to those who still believe the Roma to be somehow undesirable. It is a celebratory record of a time during which this perennially tyrannised culture was allowed to explore itself in public, and a fascinating history of a period of remarkable innovation.

The Quietus caught up with Knox to discuss the process of compiling Stand Up, People, and the turbulent histories and political and social upheavals that were taking place while it was being created.

I read the article you wrote for Sarajevo Notebook as I was listening to the record for the first time.

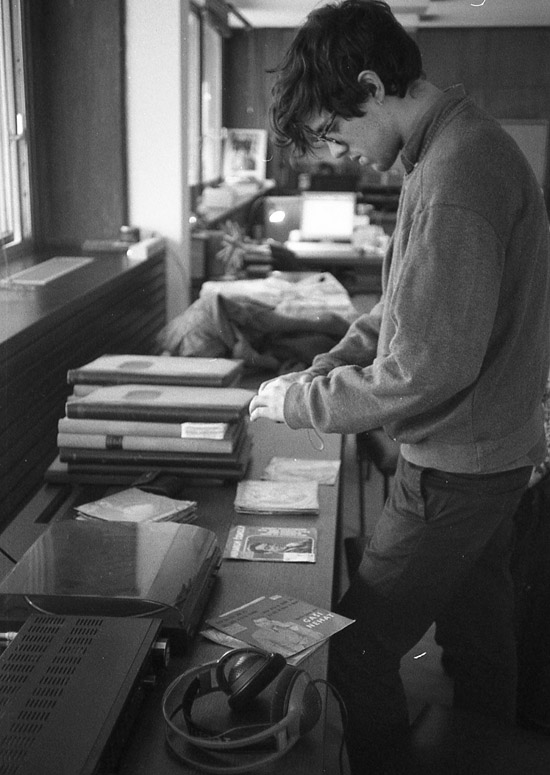

Philip Knox: The big trip that article came out of was nearly two years ago. That was about a six week, two month trip. Then last December we went back to Belgrade, because a lot of material that ended up on the CD was from the National Archives [of Serbia]. We knew these recordings existed, but we’d never found them anywhere in all our digging. Some people thought they didn’t exist, but we went and dug around in the stacks of the National Archive and found them. Fortuitously they had some stuff we really wanted, and we had some stuff they didn’t have, so we struck a deal and were able to temporarily borrow that material and get it digitised and restored in London.

So there is a big storage space full of records in Belgrade?

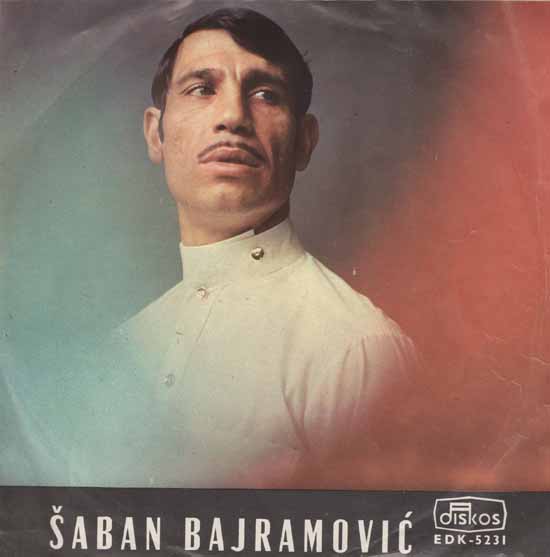

PK: Yeah, it’s quite amazing. Under Tito they took copyright copies of pretty much everything, in theory. When we went it was quite chaotic. It had only just reopened, and I think we were some of the first people through the doors. Unbelievably, in a way that would never happen in Britain, in a quite Balkan style, this lovely librarian said, "Yeah, go and have a look." So we were in the stacks, just rifling through these records and pissing our pants because there was all this stuff we wanted so desperately. We were able to photograph some of the sleeves as evidence that this stuff existed – particularly some of the early stuff by Šaban Bajramović [who appears three times on the compilation], who later in life became a sort of world music star, and was relatively well-known in Europe. But no one believed he’d released stuff before 1991; no one believed it was available. So we found loads of stuff by him, and we were really excited about it, but we couldn’t listen to any of it, because they hadn’t set up their A/V room. That was part of the reason for our return journey last December – to go and actually check this stuff out. So although we were quite far advanced with the CD at this point, and knew there was stuff that had to go in there, we didn’t actually know what it sounded like. It was quite a gamble.

How did you go about selecting those tracks?

PK: The fundamental rule was stuff that we really loved. There was stuff we wanted to say by including certain tracks. We wanted to represent lots of female singers, and we wanted to represent lots of stuff that was arrestingly unusual, and contrary to what people would expect. By coincidence, that tended to coincide with what we liked.

Is that strength of female singers representative of the scene as a whole?

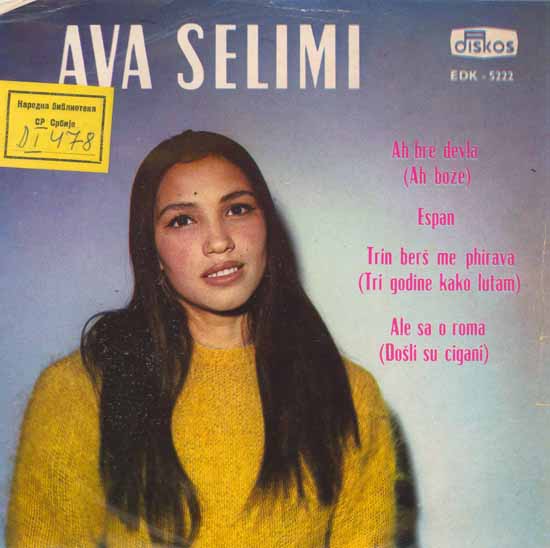

PK: I think it is, yeah. It’s quite difficult being a female Roma. It is quite a patriarchal society, and if you’re a woman in a patriarchal society that is inherently more marginalised than any other society, you’re even more on the fringes of things. So it was remarkable to find female singers being incredibly successful, managing their own bands, going on tour. Some of them had difficult stories associated with that; it was no paradise. There’s one singer, Ava Selimi, who only released one 7" that we got our hands on. We never managed to track her down, but we do have anecdotal stories about her from people who knew her. There is this rumour that she was rejected by her family and her community simply [for] being a performing musician and being single, and instead of fulfilling the traditional role that they might expect. There is a suggestion that she just left her town in Kosovo for that reason; she now lives on an island in Croatia.

Let’s talk a bit about Esma Redžepova, who features heavily on the album.

PK: Esma Redžepova is still quite a celebrity in Macedonia. She was in the press in the region recently; she was one half of Macedonia’s Eurovision entry in May. The other half was this rubbish rock singer, whose name I forget. She reached a remarkable degree of celebrity in her own time, in the 60s and 70s. As a young woman, basically in the ghetto, I think she did struggle. She had to sneak out of her family home to perform, and it was very much against her family’s wishes that she did become a performer, not only within Roma communities but also nationally and internationally as a Yugoslav.

Were there other artists who reached that kind of level of success at the time?

PK: She is quite unique. Šaban Bajramović, a little later in life – they were thought of as the king and queen of gypsy music, even though they were from different places, and I don’t think they ever performed together. He reached a fair degree of recognition, particularly with some recordings in the late 90s that had a sort of Buena Vista Social Club style. But at the time Esma was relatively unique in terms of the enormity of her success.

Would you consider the 60s and 70s to have been the most important period for that music, or is it still continuing today?

PK: There’s still lots of amazing music by Roma in the region, and lots of performers who are Roma, but aren’t necessarily publicly. They’re just pop singers or whatever – they’re not pretending to play folk music. But I think the era of Roma musicians singing in Romani, identifying completely, unproblematically as Roma, and being consumed on a national level – I think that’s gone. I think that’s mainly a casualty of the ethnic wars of the 90s, where people just became so hyper-tribal that the Roma were always external to each of these fragmented groups, and were always persecuted a bit more, particularly in Kosovo where I think the population was reduced by 80 per cent, partly through mass execution and partly through [the exodus of] refugees, a lot of whom ended up in Macedonia.

And is Macedonia the hub of the Roma community now?

PK: It’s got the biggest Roma settlement in the world, just outside Skopje – a place called Šuto Orizari. That’s quite a unique place. You walk in the street and there is Romani being spoken everywhere; there are signs in the shops in Romani. It’s amazing. But in terms of population, there are enormous numbers of Roma in Serbia, and other parts of the Balkans outside the former Yugoslav countries, like Romania and Bulgaria. Whether Macedonia constitutes the hub of the culture is quite hard to say – they’re all quite different. Whereas in Serbia the Roma might be more urbanised and live in a more integrated way, that doesn’t necessarily make them less Roma or less significant culturally.

Although there’s quite a big Roma population in Bosnia and Croatia, it’s weirdly quite a quiet population. They don’t have this sense of playing Roma music, although a lot of them are musicians and will play the local folk music. But there isn’t a scene, and there wasn’t even a scene in the 60s and 70s, even though there were plenty of Roma and they were culturally and politically active. We were curious about that, and asked some of our Roma contacts in Bosnia why that seemed to be, and they quite depressingly attributed it to the success of the Ustaše fascist anti-Roma campaigns in the Second World War, where you would be shot if you spoke Roma or looked Roma. The culture was driven underground and never really emerged even when it was safe to do so. It became a domestic and private thing, which never quite happened in Macedonia, Serbia, and Kosovo at that time.

Photo taken on Knox and Morris’ trip to Belgrade

It’s interesting that there was this flowering of Roma culture during Tito, while at the same time Tito was very uncomfortable with expressions of nationalism. Do you think those things are hard to tally?

PK: I think they’re precisely parallel, and consequences of one another. By trying to reconcile an incredibly diverse and historically ruptured part of the world, Tito’s strategy was to enfranchise to some extent every minority. There were different hierarchies of it. You could claim to belong to the nation of Croats, or the nation of Serbs, and you had an identity to that extent. But also Roma and Albanians had these ways of identifying themselves on their identity cards. I think as a consequence of trying to present a slightly more inclusive way of people being Yugoslav while also not having to renounce their previous identity, the Roma got for the first time a look in. All the identities had to be represented, otherwise it wouldn’t work.

They had a way of identifying themselves publicly. They had cultural groups in a lot of the villages, in the same way that they would have Albanian and Turkish cultural groups where they would get together and organise concerts and music, and probably spread party doctrine as well. So it’s quite an unusual and unique time, and it’s in stark contrast to the strategy pursued in for example Bulgaria, where it was outrageously monocultural, and speaking or singing in Romani was illegal. The Roma continued to be there, and produced lots of music, but it was all Bulgarian music produced by Roma pretending to be Bulgarians.

Does that remain the case?

PK: All that part of the world remains horrifically racist against Roma. The prejudice that was always there has become more public than under Tito. But Bulgaria has improved slightly from when it was really bad. At least there’s no official state apparatus actively shutting down the Roma voice, although prejudice on the level of community is always harder to police and assess.

And how quickly did that boom period end after Tito?

PK: It’s hard to say. Society started to collapse quite quickly after Tito’s death, and in some ways it was already on the way out. His death coincided with the emergence of lots of nationalist agendas. Even before he died, in 1980, the culture was changing slightly. Globally, the first stirrings of the end of the Cold War were starting to emerge, and nationalism was becoming more of a thing. And also the music itself – that’s when you start to see the emergence of this thing called turbo-folk. That was the soundtrack of the Balkan Wars, which ironically seemed to emerge from some of these Roma singers, who were always pursuing the most modern and fresh-sounding thing. It ended up producing the style that would become most associated with Serb deaths squads, which is one of the weird twists that are so hard to reconcile.

The 80s were just stylistically a different time. Production values just fell, especially in Yugoslavia. So while it’s probably impossible to say "Here is the golden age", basically when society started to fall apart, the structures that had enabled that music to be produced fell apart too. The singers that remained successful stopped being Roma singers. A lot of them keep going – Esma keeps going through the war. She stops singing in Romani, and stops doing these gypsy songs. One of the more extreme examples is this guy called Muharem Serbezovski, who was a Macedonian Roma. Most of the Macedonian Roma are Muslim, and he spent a lot of the war in Sarajevo, and identified really strongly with the Bosniak cause. He started singing loads of Bosnian war songs, and totally naturalised as a Bosnian. After the war he joined the Bosnian National Assembly as a politician. He presumably had some kind of affinity with Bosnia because it was the Muslim capital and he was Muslim, but he kind of stopped being a Yugoslav Roma singing in Romani and other languages, and started being a Bosnian.

One of the most extraordinary things about the collection is the sheer volume of sounds and styles present in it. How accessible was other music during that period?

PK: It is amazingly diverse. You get quite standard, ballady pop music, and really straight, mainstream accordion music. That’s far from a universally representative collection, even within Roma music. You get differences up in the north. Where there’s a big Hungarian population the music is more thumping, four-square, fiddle hoedown music. I think a lot of this stuff, if you weren’t familiar with it, would have sounded quite striking. People are used to a diversity of music, but if you were, say, an urban, non-Roma trendy kid living in Belgrade in the 60s and someone played you some of this crazy Kosovan Roma music, I think you’d find it quite alien. But people did buy it, which is one of the interesting things about it, and one of the things that are quite hard to explain. Everything was hyper-local and hyper-specific, but was being released by major record labels in all the urban centres, and seemingly being bought and enjoyed.

So it was a profitable enterprise as well?

PK: All the labels were part-state owned. It was an ambiguous, partly nationalised grey area. It’s not clear how far their decisions were controlled by the state. Probably not enormously, because there was so much stuff going out there that no one would have the time to go through everything. But people did buy records. Yugoslavs were quite affluent compared to the other socialist countries in Eastern Europe. They could travel, and they did. They could import Western goods; they imported Western music as well. The things people are always trying to sell for loads of money in the Balkan record shops and stalls are the Yugoslav pressings of The Beatles, or Stevie Wonder, that some crazy collector wants to get.

Another key part of this story is your own record collecting. How long have you been collecting Roma music?

PK: I’ve been following it for many years, in a quite amateurish way. There’s a couple of labels that are doing some interesting stuff, particularly with these brass bands, some from Macedonia, some from Romania, that are quite funky and have had a bit of a renaissance. Mahala Rai Banda, and Kočani Orkestar, and people like that. I was always really into that and so was Nat, and we would chat about that, and we’d independently travelled around the Balkans a bit.

Esma Redžepova came and played in London in about 2006 with Mahala Rai Banda, and it was an amazing gig. Weirdly, for a ‘world music’ audience in London she’s quite a big deal. I’ve always been into collecting records and getting my hands on originals, in quite a nerdy way, and I wondered whether I could get LPs of Esma’s stuff. You start to look around on the internet and find things. We got a couple of bits and bobs and thought, "Holy shit, this is really good". Then we started taking it more seriously, and grabbing anything we could find. And then, after we’d got together quite a small pile of records, this seemed like something quite important that had been missed by the standard narrative of music in that part of the world. That’s when we started taking it really seriously, and going out there with the express purpose of collecting records, but also at the same time of meeting musicians and trying to learn more about the scene and more about the circumstances of the production and release of the records.

Feature continues below photo

Did many of those artists know each other or play together?

PK: There was a scene that circulated around Esma and her husband. He wasn’t Roma, but he was a big music mover and shaker. A lot of musicians went through their sort of academy. They would take on a lot of Roma musicians who would then splinter off and do their own stuff. So Muharem Serbezovski – his first gigs were playing with Esma’s ensemble. And Medo Čun, who plays the second to last track on the record, the big instrumental, whose importance for the entire Roma music scene can’t be stressed enough – he arranged so much, and was a real hub – his first job was playing clarinet for Esma.

It seems similar to the jazz world, in that you have frontmen and sidemen.

PK: It bears an enormous similarity to jazz, not just in the structure of the market but also the extent to which face-melting improvised solos are part of that tradition. It’s one of the things that makes it quite compelling, especially if you see it live at weddings, where a clarinet player or sax player will just go off on one for about ten minutes. It’s quite an amazing sight.

You’ve said that the big record labels were part-state owned, but those aside, was there an independent culture?

PK: There were quite a few labels. They weren’t centrally controlled as such. All the major capitals had a label, or several. There were quite a few in Belgrade, particularly. So you have the regional publishing arm of the state broadcasting company, then you have smaller ones that do have a more independent feel, but you can’t really notice a difference in the quality or the nature of the recordings they were putting out.

Were there labels that specialised in that music?

PK: Not so much – that’s what’s strange. You’ll find extremely obscure Roma music being produced by probably the biggest label, Radio-Television Belgrade, all sung in Romani from an obscure corner of Kosovo. Then you get quite mainstream music being released from a little office outside Belgrade. It’s quite a surreal phenomenon. I don’t know if it’s the nature of how the quasi-market driven thing worked, but it didn’t seem to be competitive in that way, with bigger artists going to bigger labels and smaller artists going to smaller ones.

How was the process of getting these tracks licensed?

PK: Absolute nightmare. It was far and away the hardest, most difficult, longest, and least enjoyable task. These labels were partially state-owned by a country that doesn’t exist anymore, or have reverted to partial state ownership and partial private ownership in new states. Many of them don’t know they own the rights to these tracks, and first you have to convince them they do own the rights before you can license them. The difficulty of that is one of the reasons why a release like this has taken so long to come out. No one else is mad enough to spend two years Skypeing really angry Serbians.

It’s as true of Yugoslavia in the 1960s as it is of most music today – it’s entirely set up to minimise the amount of money artists get, if not eliminate any money. The rights of ownership artists have is so small. It’s something we really struggled with, because we always wanted to give something to the artists when we could find the ones that are still alive. A saddening and quite depressing thing about it is that we encourage these artists to sign up for these incredibly complex international rights collecting systems because they might stand to get some money, but a lot of the time it’s not worth it for someone who’s not a native English speaker, or not very good with computers.

Do you see the potential for a resurgence of interest in this music?

PK: Young people from the former Yugoslav countries, when we talk to them about this, they’re just completely confused and bemused. Then we play them the music and they are astonished that there’s stuff from their own culture that could sound like that. So much of the non-Roma idea of Balkan music, even in that part of the world, is totally informed by all this bollocks like [Emir] Kustarica. That’s really monopolised people’s idea of what their own music is – something really primitive that comes spilling passionately out of them; something not quite under their control; they might steal your TV but they also make this lovely music. Then people are surprised that there is this incredibly sophisticated, sensitive music about complex ideas. I think if people got their head around that, that would be really great, and that might mean that some of the musicians that are still around might get to revisit some of that stuff.

The Stand Up, People compilation is out now on CD, LP and digital formats via Asphalt Tango Records