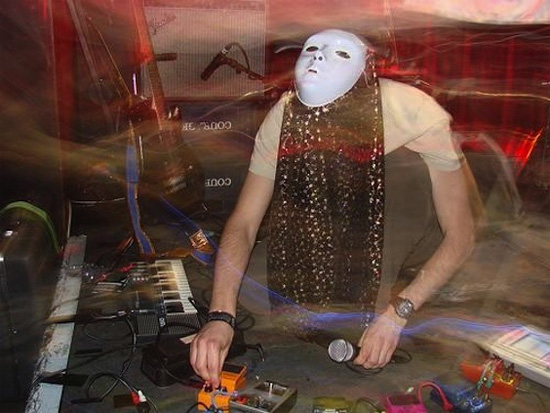

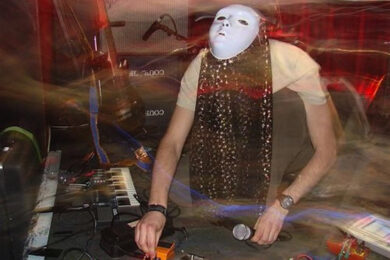

Saturday night in Cambridge, and it’s the last night of High Wolf’s tour with Ensemble Economique aka Brian Pyle of Starving Weirdos, following an Exotic Pylon show in London. As more than one person has clearly pointed out to them, it’s a funny package in that it features a Frenchman with a non-French name and an American whose name makes him sounds as though he’s French. This show here has been put on by Bad Timing (stalwart ‘experimental, electronic, noise, lo-fi, radiophonics, DIY, weird pop, randomness’ promoters in Cambridge for nearly ten years), in one of the city’s currently dwindling number of small venues, CB2. The gig room is actually in the basement of cafe and comes with attendant noise restrictions, a fact that results in High Wolf’s performance being curtailed when the conscientious sound guy tries to mitigate the introduction of an extra, screeching guitar effect and pulls the volume down slightly too sharply. It’s enough for High Wolf (real name Max) to lose his flow, or maybe to un-lose himself in his weaving guitar-and-electronics improv, and soon after he brings the set to an abrupt halt. It doesn’t come across as a fit of pique particularly, it’s just the moment has gone, the trance has been broken.

High Wolf’s attracts and consciously cultivates mystical/spiritual associations; Ascension, released on Not Not Fun in 2010, features a track called ‘Solar System Is My God’, his own label is called Winged Sun and the music is based on loosely ‘tribal’ sounding rhythms, drones, distantly echoing vocals, tendrils and wisps of guitar and synth winding their way through the mix as the whole drifts on unclimactically. All this may could come over as just vaguely post-New Age pick ‘n’ mix but Max is lucid in discussions of his ‘personal’ spirituality and how it relates to the global musics he draws on. Because of this, questions about globalisation, the formation of new kinds of communities (not geographically based but forming via the internet) and the concomitant erosion of cultural specificity seemed especially relevant.

Max also has numerous alter-egos, including the one responsible for his next release (in September) of Life Is An Illusion, credited to Annapurna Illusion.

How long have you been touring for?

Max: Not that much – a week and a half or something like that. I’m touring with Brian (Ensemble Economique), we met in the States when I was touring there last February and March and we were invited to the same festival in Denmark in early August so we decided to do more gigs together and do the half-vacation, half-touring experience.

Have you actually collaborated at all?

M: We played together live in the US and we have ideas about future stuff, but we haven’t done anything yet. I think that now although we share many interests in music, we are taking slightly different roads.

What do you mean by that?

M: It’s hard to explain, but it’s more in the aesthetic – he’s now incorporating lyrics into his set and using more pop elements in his music, which is fine and he does it very well, but I’m not there yet, I’m still trying to figure out something different.

Are there any reasons why you might be hesitating about writing lyrics?

M: There are many things – first I’m too picky with words to write songs myself, it always seems to come out a bit stupid, but that’s very French I guess. For instance, with pop music in France. Even though it’s dying now, but in the history of French pop music you need to have good lyrics, political or intellectual, but something deep, and then English-speaking pop music, especially from the US, is about "I love you baby" or whatever, and they don’t care about the meaning sometimes. So for me, if I want to have lyrics and turn the vocal sounds into something that has meaning, then it really needs to mean something.

So may French artists I speak to say the same thing, particularly about the pressure of writing in French, and they feel freer writing in English.

M: That’s a good point because if I wrote lyrics I think they would be English lyrics because it would be more abstract to me, and I could go away from this thing about the poetry and the articulation of the words. I mean, French is a very beautiful language and you don’t want to mess with that I guess.

There’s always this pressure of the greats, the great chanson songwriters…

M: Yes, but that exists for English-speaking countries too, so I don’t know why we are so into that idea. But it’s totally dying if you like, what’s on the radio right now… I mean, for my parents’ generation you had those guys like Jacques Brel. It doesn’t mean that I like the music, but it was beautiful stories, the songs were very deep and emotional so that was a good level, but it’s not that good any more.

Another thing I have noticed is that a lot of musicians from France making music that isn’t necessarily variété, pop don’t feel particularly attached to their own country musically. I think that happens more in France that the UK. And it applies very much to you I think…

M: I don’t think there is any real French identity in music. We had our fair share of classic composers but since the 20th century there haven’t been any French bands that have been world famous. There’s this famous quote, I don’t remember exactly who it’s from, but probably someone from The Rolling Stones said "French rock & roll is like English wine". And I think, yeah, it’s true. I don’t know what’s French in my music, probably nothing I guess.

Obviously the way music is made and distributed and the way that you enter into contact with your peers has, in your experience, been liberating. For someone who doesn’t feel that inspired by their own country’s musical culture, it’s a good musical moment to be around in…

M: Yeah, I guess now we all have the same references. If you were growing up in France thirty years ago it would have been hard to find new records from those obscure, underground bands, and now with the internet the cultural base is the same everywhere. So now when I speak to friends in the US, we all grew up with the same movies, the same bands, so it feels like the national identity is something that doesn’t have as much power in your education, your cultural education. Obviously there must be some differences that come from the fact that I’m French, compared to the other guys who happen to be in the same musical community, but it’s nothing to do with music and arts.

As far as you’re concerned, are there any losses in terms of the disappearance of that specificity?

M: I don’t know… I think the more information you have the better it is for you, because you can pick what you like and what you want to do with it. But even then there will be some cultural – not in the sense of arts, but education and things like that – I think you will reject some of [that] information, through pre-determined tastes that come from your background and your parents.

For my generation at least, you have all this information coming from all over the world so you have great access to every resource, you haven’t grown up alone in a bubble. So you have your friends and your family and that creates some kind of barrier, a filter… So it’s a good balance between the fact that on your own you are going to search for information, but you are also going to be influenced by other people’s opinions, and there are things that you are not searching for that people give you. You take stuff from all over the world, but at the same time your parents or society are giving you something that might be more… nationalist. I don’t like the word, but…

It sounds as though you’re saying that because of your context or your early influences, you might be filtering information in ways you’re not aware of.

M: Yes, of course. It’s a long debate, there is free will but there is also this subconscious area that we’re not in control of, and the shared unconscious, it’s somewhere there. I think it’s well-balanced now, but it has been going super fast. Maybe the next generation will be more lost in this, with national specificity decreasing, not only culture and arts but… It’s globalisation, so you can always talk about whether it’s good or bad, but it’s definitely happening. I think there is no way to fight against this, it’s definitely stronger than us.

Another way of looking at the issue of specificity is that you’ve travelled a lot, and the music and instruments of different countries find their way into your work. This is not a new question but do you feel any responsibility to particular cultures when you incorporate elements, rhythms or instruments that may have a particular religious significance into your music?

M: It reminds me of an article I read a few years ago by Sun City Girls, and a lot of people were very angry with them for using sacred instruments in a very weird way. I think they were right when they said it would be less respectful to try to do the same thing when they don’t have the same religion or education, they don’t know the country. Acting as if they were from a country, and using the instruments in their way, would be less respectful of their culture than to try to incorporate it into their sound and ideas.

You mentioned something very delicate, the question of religion – if something is sacred it’s very touchy. But there is a way to use that if you’re very honest, you can use something in a different way but respect it as much as people who use it for a religious purpose or very important social ceremonies. I think there is no problem if you are true and honest, because I know that I translate these religious aspects from those instruments… For instance, I bought this drum in India that is used for religious ceremonies that have been happening for thousands of years, so there is this spirituality around the artefact that is just wood, but the human spirit has created this vibe around it. I will totally integrate that idea and add my personal feelings about this. To this drum that has its own spiritual vibe, I’m going to add a second layer in a way – my personal memory of this journey, of when I bought it, on a specific day in this specific shop. When I use it at home all those things pop up in my brain – it’s a new layer of spirituality, a self religion in a way.

It may not be an easy thing to do but is there anything concrete in your music you can point to that demonstrates how this ‘second layer’ works?

M: It’s purely psychological in a way, I think if I bought the same drum in my own city, there would be no personal history attached to it. It’s not something I’m 100% aware of all the time when I use it, but it’s something special. One concrete example is that one day I was making a track and using several layers of different instruments, then I realised that, let’s say there were seven tracks on this piece of music, and I used one drum that I bought in India, then another drum I bought in Nepal, a shaker from Morocco and another thing from Mexico. It’s a connection to all my inner experiences from the past, very deep and strong emotions that I lived in all those countries. They’re memories that are translated into objects.

So if you add the shaker from Morocco to the track, that is going to colour it in quite a particular way for you.

M: Yes, it’s something purely emotional and personal. I don’t know if that can be sensed by the listener but what I can say is that it really exists.

You don’t really give out much information about where you’re based and I suppose that’s partly because you’re quite nomadic but also it’s related to how you want your music to be received?

M: You know, when people ask me ‘off-mic’ where I’m from I talk about it so many people know about it, but it’s just that a) I don’t think it’s that relevant in a way, and also I want the music to be the one and only focus, and I’ve learned that any information is a way of influencing a listener in one way or another. So if I want to be cool in 2009, I can say ‘Yeah I’m from Los Angeles and doing this thing’, or in 2000 I say I’m from Montreal or Chicago. So any information that is around the music, it might be unconscious, but it creates something that is around the music, but is not the music itself. So that was an idea to remove as much information as possible to let the music speak.

It has led to some very awkward situations sometimes, like three or four months ago a guy who lives in the same city as me, which is not a very big city, wrote an email to me in English to ask if I was willing to play a gig there, so I replied to him in French and said ‘I live in the same city as you’. Those funny things happen, and often people say ‘Oh I thought you were from America or the UK or Brazil’, because that was the location that was on my Myspace. So those are slightly serious reasons but the main part is – who cares about that anyway? And it’s funny as well, because now with the internet community, even in our very, very small world that interests only a small core of people, you give out a piece of information and it travels very quickly. Obviously I’m not doing it now, but in an interview you can give a fake piece of information and you’ll see it months later, people reviewing records or promoting live events will use those totally wrong facts because they just search in Google and find it and cut and paste. So that’s a funny tool to play with, this internet craziness.

I guess you began playing by yourself and recording alone.

M: Yes. I guess that’s related to the first thing we talked about, being French. So I started being interested in certain types of music, more experimental and of a very specific kind, so when it came to the point of trying to do my own thing, no-one was interested in that. I guess maybe if it had been 50 years earlier I would have just taken an accordion and played French popular music, and I would have found many people to play with me and it wouldn’t have been a problem. But because I was looking for a very specific thing, the people who are interested in the same things are spread all over the world. I mean, you can always collaborate with those people but it’s not very practical. I never wished that hard to be a solo performer but it was just a practical thing. At first I didn’t know how to play any musical instruments at all so I started with that, and then I said ‘Oh I wish some guy would play guitar with me – ok, no-one?’, so I played guitar myself, and then ‘Who wants to play synths? No-one’ so I played the synths myself. But now it’s not that bad, because it gives me a great freedom, and I can travel and tour a lot and it’s not as difficult as for some friends of mine who have bands with three, four or five members. So it’s come to be an advantage but at first it was kind of an obstacle for me. I’d talk to people and I’d be like ‘Are you sure you’re not interested?’ and they’d be like ‘It’s too far out’ or ‘It’s not experimental enough.’

The current name being used by your touring partner, Ensemble Economique, seems like an apt description for a lot of performers of a certain kind at the moment – just one or two people, kit they can carry easily, maybe they’re a couple…

M: Yeah, maybe it’s lame to say that, but even at our level which has always been difficult economically, it’s getting harder and harder to tour. If you’re a band in Europe and you want to tour the US you have to rent a vehicle and backline, and you have those fees that, if you are six people, you lose so much money.

You have been building up a number of side projects and alter-egos, like Annapurna Illusion. What’s the spur for these?

M: It started at the same time as High Wolf and at first it was a very simple, black and white situation – High Wolf would be like the white thing and Annapurna the black thing, or like moon and sun. I have this tape I made which was the first split between those two projects, called ‘Soul Division’, and I think that explains the thing – it’s like an inner division. It’s because I’m interested in a lot of things, some projects that go more into electronic music or hip-hop or whatever, and I don’t think you can really mix all that in one project, if you try to mix too much it doesn’t work. With Annapurna, I’m a big fan of Earth or Om, a kind of stoner rock vibe that would not totally fit with High Wolf. And it helps me to be inspired and motivated.

It might also be that if I was only doing High Wolf songs I would be scared of pushing it too hard and letting it go too quickly because I’ve had enough of it. I mean High Wolf takes most of my time I think, because it’s the thing that suits me the best, where I have the most freedom to do many things. But in the past two or three years I think I’ve had easily five or six solo projects. Some will die very quickly and some are like Annapurna, where I’ve done seven or eight tapes and the split with High Wolf and this new LP, so it’s one of my most important side projects. It’s like an impulse as well, like I made this tape called Black Zone Myth Chant which is some kind of weird hip-hop project. I’d never really thought about that before but one day I started to do something and then I made the full tape in three days, doing only that and really into it. In those moments I feel like there’s no way I’m going to do anything else in my life, it’s going to be only that… but then after three days I switch to something else.

For more from Rockfort, you can visit the official site here and follow them on Twitter here. To get in touch with them, email info@rockfort.info.