"At once a scathing indictment of the injustices perpetrated on the homosexual community, a proud proclamation of gay identity, and a love letter of bracing intimacy and eroticism, the album radically appropriates the signifiers of the conservative country genre, queering its heteronormative vocabulary into a deeply personal language."

Now that was promotional blurb to grab our attention. The LP that Brendan Greaves and Christopher Smith of Paradise Of Bachelors were waxing so lyrical about is Lavender Country, recently reissued by the North Carolina label. Sponsored by the Gay Community Social Services of Seattle Lavender Country’s self-titled 1973 release was cited by Nashville’s Country Music Hall of Fame as the first openly gay country album. This would be enough reason to delve deeper, but even without the intriguing narrative this is a re-issue that you need to hear. As soulful as it was revolutionary Lavender Country filtered the country storytelling of Lee Hazlewood and the psych-folk of the Holy Modal Rounders through the theatrical lens of surrealist drag troupe The Cockettes. But who was responsible for this fearless and unique LP?

Raised on a dairy farm in Dry Creek, Washington on the border of Canada, Patrick Haggerty moved to Seattle in 1970 in the empowering aftermath of Stonewall. There he created Lavender Country as a reaction to the prejudice he had experienced at first hand, penning numbers like ‘Back In The Closet Again’ and ‘Cryin’ These Cocksucking Tears’. Becoming involved in Seattle’s burgeoning gay rights movement, he used the band to spread information on gay rights to those who might not have received it elsewhere. Where the gay community in cities like New York and San Francisco expressed their newfound freedoms though disco in the years after Stonewall, Haggerty chose country. "Maybe it was a brazen thing to do, to come out with a gay country album: On the other hand, why not?" he says in the sleeve notes of this timely re-issue. "I think we forget that gay people come from everywhere. And I came from Dry Creek, Washington…listening to Patsy Cline."

In the same notes he describes the tough but loving environment he was raised in by his tenant farmer parents. "The downside of my childhood was the huge amount of labour that was involved that was way too much for any child. But the upside was that I had committed, intelligent devoted non-abusive and engaged parents," he tells me over the phone. It was certainly needed in the small farming community where he was raised. "Dry Creek was idyllic in terms of its setting. It was really very pretty. But it was also very stereotypically American 1950s redneck. There was rampant racism especially towards the Native Americans. Then there was the other abuse such as wife beating and of course homophobia." But despite "running around Clapham County, Washington with a bunch of redneck loggers in drag," his family shielded him from the worst of the hate: "My father died when I was 17 but he was more aware of me as a homosexual than I was. He saw where I was headed but I hadn’t wrapped my mind around it yet. He was very progressive." Before he died his dad left him with some guiding words. "He told me ‘not to sneak’. Isn’t that an amazing thing to say? I didn’t want to know what he meant at the time. I knew but it was before I came out to myself. He was dying when he told me that. That was in 1960." His father passed away a year later and Patrick went through the sixties in the closet.

In 1966 he was thrown out of the Peace Corps for his relationship with another man. After being interviewed by their psychiatrist he was left depressed and confused. He would return to this and the punishment of gay people at the hands of 1960s state hospitals on ‘Waltzing Will Trilogy’ one of his most poignant songs: "They call it mental hygiene. But I call it psychic rape," he sang. As he puts it in the sleevenotes: "It was a mess, I had no information, there was no help. I had to figure it out for myself." But his life would be changed by events thousand of miles away in New York. "I came out with the Stonewall rebellion," he says. "I had barely turned sixteen when my dad told me not to sneak. But I had to go through High School, I’d been through college, got thrown out of the Peace Corps, and all the time hiding. This was all before I had a conscious gay identity to so it was a very traumatic experience for me. I was in a place called Missoula, Montana when the Stonewall riots happened. And as soon as I heard about the riots I was out that day. Right away, boom. I was so ready I came screaming out."

The Seattle he discovered on arrival in 1970 was everything that Dry Creek wasn’t. "Seattle was a great place to come out. It was probably one of the top four cities in terms of being a favourable environment to be gay. And if you were going to be part of the gay liberation movement it was a great choice. Seattle was ahead of the curve on the gay issue from the beginning. Don’t let anyone tell you that San Francisco was the seed of the American gay movement because it’s not true. Seattle was ahead almost every time. It was the first in a lot of things. San Francisco was probably more of a Mecca socially but not politically." After years of hiding Haggerty made up for lost time: "I went to a gay liberation meeting in the summer of 1970 and it was at someone’s house but that fell apart. So then two months later I was doing a gay liberation collective out of my house. There was already a counselling service for homosexuals in Seattle and it became the seat of the lesbian and gay movement. There was also a Gay Community Centre there really early on. There was a lot of movement that came out of there. So those were the two places that the activity came out of."

Patrick had first heard country music like any young kid in isolated rural America across the airwaves. "Where I grew up I was 100 miles from the nearest concert venue. I never went to a concert as a child nor did anyone I knew at the time. Nobody did, they were too far away. So whatever music we heard was what came over the radio. And that was 80% country music. Patsy Cline and Hank Williams and that whole set. That is what I grew up with and cut my teeth on. That’s what I knew and loved." Were there any particular singers he connected with? "I was pretty drawn to female country singers," he says. "Tammy Wynette, Dolly Parton, and the earlier ones like Patsy Montana. I was drawn to female country, I really was. I still am." Again it was his parents who helped him, as music became his great love. "My dad bought me a guitar," he says. "My parents were atonal, they really were. But they noticed I had a musical flare and my father responded to it by buying me the guitar. Our little four-room school was blessed with a principal called Mrs Thomas who was a gifted musician. She taught me a lot. I got the fundamentals of reading music from her." While he was too busy with the farm to do music in his early teens, he remembers getting seriously into playing when he got to college.

Despite becoming known in Seattle as a singer and guitar player, Lavender Country was Haggerty’s first band. It began with a song directed at the left wing movement. "’Back In The Closet Again’ was my first song," he says. "I thought it was so ironic that we were having to kick our way into the socialist and progressive movement, never mind mainstream society. They didn’t want to hear about homosexuals either. So that’s what that song was about." On hearing the song people in the movement encouraged him to write more. "Then the idea of writing a whole album of gay music came up amongst the people we were working with. And many people started to get behind it," he recalls. The band he assembled included three other gay musicians, including his pianist friend Michael Carr and fiddle player Eve Morris who wrote ‘To A Woman’.

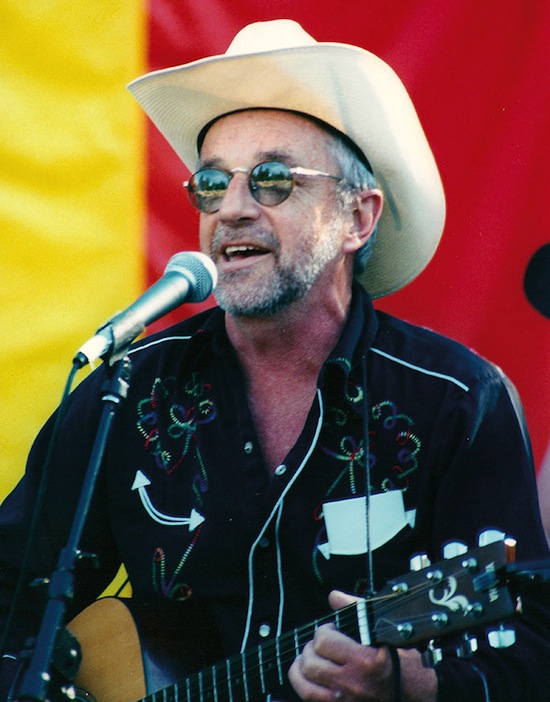

Only surviving band photo of Lavender Country, 1970s

As soon as word got around about the plans for a gay country LP the community provided support. "I want to emphasise really strongly that I could never have made Lavender Country by myself. I couldn’t even consider it," he says. "The lesbian and gay movement in Seattle took on Lavender Country as a project. There was so much to do. And many people were involved, not just the musicians. We had to raise the money. We had to figure out a way to try and distribute the album, and we had to get a PO Box, and to keep track of the money and borrow money."

Pressing up 1,000 copies of the LP with the support of the Gay Community Social Services and various donations, they spread the word of a gay country LP through mimeographed ads in gay underground papers. "The people we made Lavender Country for were the gay and lesbian people across the country that were in the closet. That was the bunch we made it for. I don’t think anyone who was interested in buying gay music in 1973 turned down the LP because it was country. You see what I am saying? People were going after the information that was in the album. We were all desperate for information back then. There was very little at the time." The words of the opening track ‘Come Out Singing’ were intended by Haggerty to act like a beacon to closeted people across the country. They read: "Waking up to say hip hip hooray. I’m glad I’m gay. Can’t repress my happiness. Ever since I tried your way. Gonna lay right here and greet the sun, ‘Cause gay time lovin’s just begun. So come one, let’s tumble in the hay." Listening back to the album now, Haggerty gives a good description of the Lavender Country sound and message: "It’s a little raggedy, it’s a little rough around the edges. In some aspects it’s a little bit amateurish. But the album is valid, the album is heartfelt, the album lays out our struggle personally, interpersonally, socially and politically. It lays out the struggle of what was happening for homosexuals in America at that time. And it does it very well."

Patrick and his husband JB, 1988

They toured the album across the gay community culminating in a 1974 performance at Gay Pride in both Seattle and San Francisco. But the LP remained a cult item pretty much unknown outside of the gay community. Patrick Haggerty went on to get married and raise a family and thought Lavender Country was a thing of the past, until he was approached out of the blue one day. "That is a remarkable story in itself," he says. "What I do now with music is I have a partner who plays harmonica and we sing songs to old people at places like senior centres. We sing covers that the old folk want to hear. I’m doing that and I haven’t even thought about Lavender Country for years. Lavender Country has gone completely back to sleep. I’m not listening to it or thinking about it. Anyway without me knowing it, ‘Cocksucking Tears’ had been put on YouTube and somebody heard it and went to eBay and found a used vinyl for sale. And they knew the folks who were running Paradise Of Bachelors and took a copy to them and said, ‘Look at this’. At the time I knew nothing about eBay, YouTube or Paradise of Bachelors. I am completely oblivious and ignorant to all of this. I’m just singing songs to old people and living with my husband. And the label calls me up and offers me a contract out of the blue. Can you imagine that? I’m just minding my own business and someone called me up and offered me a contract on a record I made 40 years ago. I was just astonished. It’s like a Cinderella story, it really is." Interestingly for Haggerty was the nature of the label that approached him. "They pursue American folklore and that is perfect because that is where I now see Lavender Country. It belongs in American folklore. So the right people found it at the right time – they really did."

I end by asking Patrick how things have changed since he first conceived the project back in the early 1970s. "There has been a paradigm shift in who is interested in Lavender Country in the same way as there’s been a paradigm shift in where we are drawing these lines. When we made the LP in 1973 there was a huge line between gay and straight and in the last 40 years it’s steadily changed and that line has shifted. We are really dividing into two groups. The white, conservative, supposedly Christian, haters. They want to hate blacks, they want to hate gays, they want to hate immigrants. We all come in a package to them. On one side you have those people who insist on having this society where hate is the order of the day, and on the other side of the line are the people who are saying we don’t want that kind of culture. And so now huge numbers of heterosexual people are also turning onto Lavender Country and identifying with it, believing it’s their music. And it is."