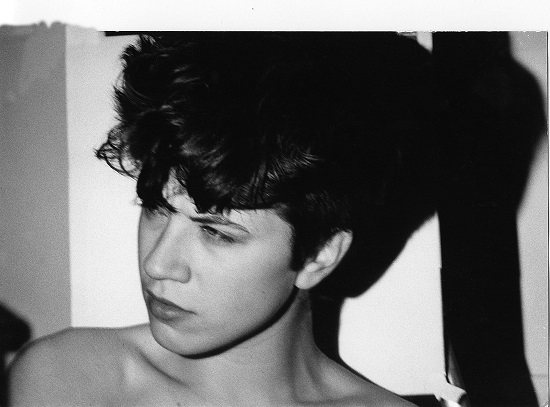

Portrait by Seth Tillet

The further we move away from them, the more past eras appear to contract as the common denominators in the music of what seemed like very disparate artists become more obvious. But in another way, some eras or sounds are also magnified by the turning of our attention to them, as we pore over and fetishise records that were largely subterranean at the time, examining minute distinctions as if we were looking very closely at the detail of the skin on one fingertip. The risk is that the weight of that attention risks crushing the life out of the music – particularly post-punk/no-wave, where spontaneity, tentativeness and fragility were part of the appeal.

But I think Lizzy Mercier Descloux and her music can take the scrutiny. Not because her records are perfect, or timeless – in fact, each successive album is firmly rooted in a particular time and place – but because the restless spirit they capture is inextinguishable. Martine-Elisabeth Mercier Descloux died from cancer in 2004, aged only 48. But on record ‘Lizzy’ persists, larger than life, too fast for death; quick as a flash, a comic book hero, a ‘Hard-Boiled Babe’.

Press Color is the first in a series of reissues on Light In The Attic that chart Lizzy’s journey from Paris and through New York, Nassau, Johannesburg, London. With recordings by short-lived duo Rosa Yemen included as bonus tracks, it documents her musical coming out in downtown Manhattan, frantic pencil sketches that give way to the full-on action painting of her album debut.

She had arrived in the mid-70s with her then-boyfriend and lifelong “partner in crime”, ZE Records co-founder and curator of her legacy Michel Esteban. “She was my girlfriend when she was 18 or 19 and for three years we lived together but when we started to work together we split because I didn’t think it was the right idea. And I was right because I’d made that mistake before, you shouldn’t sleep with the girl you work with. But she remained one of my best friends for her whole life so it was a very intense relationship for sure.”

The story goes that Michel’s Paris boutique Harry Cover (he sold T-shirts, records and fanzines) was opposite Lizzy’s apartment in Les Halles and he would see her cycling by, so he left a note on her bicycle. They worked on a magazine, Rock News, together.

“I started on my own but she came in because she was a very good writer. We published seven issues, it didn’t last a year. It was the punk movement, so after a while the feast was over. And I didn’t realise how much pressure it was publishing a magazine every month. I just started it as a fan. Especially in France there was nothing happening in that period. Rock & Folk and Best [the main French music magazine of the time] didn’t talk about that kind of music.”

Punk picked up early in France…

“It was only because that guy, Marc Zermati [punk luminary and founder of the Skydog label], had his shop at the open market in Paris, quite near to me, but the press didn’t talk about it at all. In ‘74, there were lots of kids waiting for something but no structure. New York was the place to go and where everything started.”

What happened in New York for Esteban was that he was recruited for John Cale’s SPY Records, which was home to, among others, Marie Et Les Garçons [see January’s column] and encountered Michael Zilka, with whom he would set up ZE [home to James White and the Blacks, Was (Not Was) and Kid Creole]. Esteban met Cale thanks to his acquaintance with Patti Smith, with whom he and Lizzy shared an apartment on Lafayette Street. In the loft, Patti Smith and Descloux were both writing poetry, so Esteban offered to publish work by both of them – a French translation of Smith’s Witt, and Descloux’s Desiderata, which is also set to be reprinted.

Lizzy and Patti, 1976. Portrait by Michel Esteban

Were Patti and Lizzy doing similar stuff at the time? “Yes, but poetry is very hermetic in a way so if you don’t understand the keys or the background it’s quite difficult. I was trying to translate some of Lizzy’s French poems and it’s very difficult.” Descloux and Smith appear together on the reissue on ‘Morning High’, a tribute to their beloved Rimbaud produced by Bill Laswell in 1995.

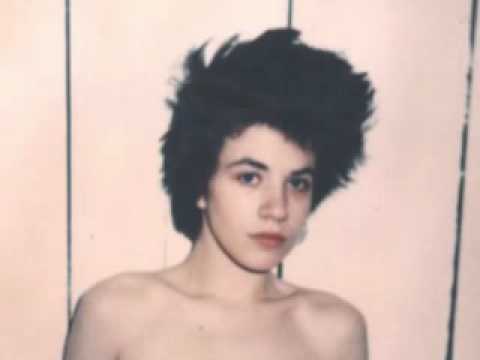

In her Press Color sleevenotes, writer and punk contemporary Vivien Goldman quotes another of Lizzy’s loves, artist and musician Seth Tillett, on his impression of seeing Lizzy for the first time at a Richard Hell concert. Hell, as it happens, was Lizzy’s boyfriend then. “Her eyes and eyebrows were incredible, she had this gigantic head of silver hair, she was wearing skintight harlequin checkerboard pants, and she was the most amazing thing I had ever seen.”

“At that point” Esteban recalls, “I don’t think there was more than 100 people hanging around, either from Max’s Kansas City or CBGBs. So we always ran into the same people every night. So obviously French people, they’re supposed to be sophisticated, and we dressed well! American people think we look good. So I think it was an advantage in a way, But to me it’s a pretty weird way…”

Goldman suggests that the French pair were a riot of colour in (small) sea of monochrome. Esteban remembers it slightly differently, “I think we were pretty black and white too in ‘75. But you know, when you’re an exile, you are different.”

Exiles in a community of outsiders?

“Yes but we also had the same culture you know. Most of them, they read the French poets like Rimbaud or Nerval and they’d seen the new wave of French films like Godard or Truffaut. And obviously we knew about their culture too, the Velvet Underground and American cinema, and so we had a connection.”

Based on her own tracking of Lizzy’s trail, Goldman suggests that Descloux was like “some exotic transplant.”

“I think maybe her voice was a little misunderstood in New York. They didn’t get her I think – she was a really a quirky, arty, bohemian Parisian and New York is really different honestly. I mean, everybody knows America is more insular. Everyone in New York had that same starved, wearing dark clothes, possibly a plaid shirt. Of course, Richard Hell developed that punk thing but in London they would have more fun. And in Paris they would have more fun still with a look. So I think she burst in, and I don’t get the sense personally, knowing the scene at Les Bains Douches and knowing the scene at CBGBs… I wondered what they really made of her because half the time everyone was so utilitarian and looking for their heroin. It was grimy, it was gritty. And she’s there with silver hair, being New Romantic-y, almost before. They were stylish in a way that New Yorkers weren’t.”

It’s the French sense of play…

“Thank you! I get the sense they really didn’t understand that. She was an adventurer, an explorer, always trying to put herself beyond her comfort zone.”

Connection and disconnection – both feed into Press Colour, at once plugged into New York scenes [punk and disco], particularly on opening track ‘Fire’, which is a very loose cover of the Arthur Brown original, but also laying the foundation for the conceptual and slightly distanced fusion of both that came to be known as Mutant Disco.

“I must admit at that time we were amateurs, and the credit has to be put to Bob Blank, the owner of the studio [the still-under-construction Blank Studios] who was also the engineer. This guy had recorded Sun Ra before and he treated us the same. We didn’t know a lot about producing music but he had a lot of respect for the ideas we had. That’s one thing I like about American people in the studio – they want you to be happy, so they really try to help you and give you the best. Mostly if the sound of Press Color is great it’s because of Bob Blank.

"We had the idea, because he was not familiar with that kind of process. Let’s take a track like ‘Fire’, which was a cover of that English song – he brought us all the best musicians, we had Tom Malone [a trombone player who was part of the Blues Brothers and Saturday Night Live bands], the guy who was the Bee Gees session drummer, so we had lots of great people. But the mix of professional and amateur, and trying to do something new, that made it.”

The whole album was pulled together on this ad-hoc basis, entirely unplanned, sessions unfolding at night depending on who was available. “There was me, Lizzy, my brother Didier, and at the time I was producing the first album by Marie Et Les Garcons, so their guitarist joined and everybody was at Blank Tape studios. There were two studios and everyone was always around so you start to record and you say “I need this guy” – everything was done in the studio.”

The results – including two versions of the ‘Mission Impossible’ theme and one of the standard ‘Fever’, which was rechristened ‘Tumour’ (the terrible irony doesn’t need spelling out) – are like thoughts in motion, lacking finish, sometimes even direction, but managing to bottle the energy of the moment through laid-back funk, reggae, surf guitar, discordant organ swells and of course Lizzy herself, childlike, birdlike, swooping from high to low and back again, scooping up random syllables and turning them over.

Speaking of his work on the following album Mambo Nassau, recorded at Compass Point studios, keyboard maestro Wally Badarou said “I can’t tell in precise words what it is she – or we – were looking for but we enjoyed the process. I guess it had more to do with posture or gesture than musicality.” Of course, this applies equally, if not more so, to Press Color.

“They’re vignettes,” says Goldman. “She’s painting pictures, being allusive. I don’t want to put her down, I mean it’s a brilliant first album, like a series of fire-crackers from the opium-soaked brain of one of her beloved romantic poets. They were up all night. Imagine the adrenaline, those hot New York nights, they were pulling in people from other studios – it’s good and bad, it has its fabulous points depending on where you’re coming from. Others would feel ‘are they earning it, or are they just charming it?’.”

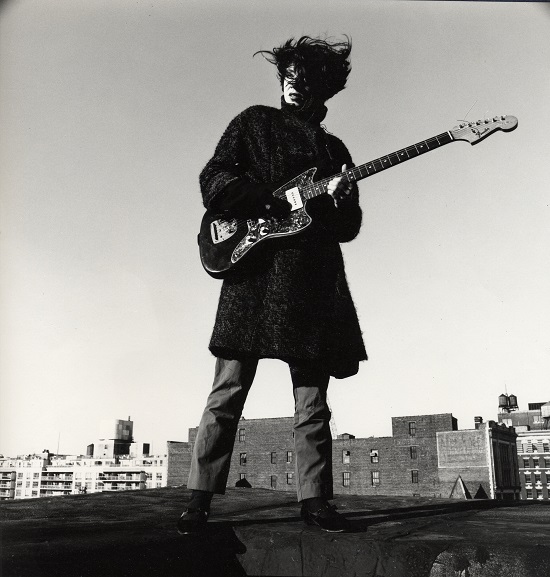

New York rooftop, 1980. Portrait by Edo

As an artistic approach, it’s also indicative of the times – it was one medium, or art project, among many. “Exactly,” says Esteban, “look at Patti Smith, she tried to play guitar on stage for years, and she learned to play 10-15 years later, and she didn’t care. A few years earlier they would have been poets not musicians. Lizzy was passionate about expressing anything she had to say. Music, lyrics, paintings and drawings were all as important. I don’t think music was the main thing, it was part of a creative process.”

But music was a popular avant-garde.

“Yes, music was the only way you could reach people. Who reads poetry books in ‘75? I think we printed 1,000 copies (of Desiderata). Patti Smith in France we only sold 3,000 copies, which was really good at that time. It was a vehicle for them.”

One of the issues with trying to get a handle on Descloux in those early days is that, at least in the notes for Press Color, the bias is definitely towards men’s (particularly former lovers’) impressions of her.

“I was a bit concerned about that,” Goldman admits “but I managed to find some girlfriends for later in her life. But, and I know it’s a temptation for all of us, but certainly when you look at her work life, her music life certainly, she was doing her own thing in a way but it was always dictated in a sense of who she was knocking around with. She was always validated by the boys, which is how she got through, but she always stuck to her guns artistically until the very end. She was a lot of fun, that’s what they tell me. I think she was more like a boy’s girl, do you know what I mean? Would pull you into mad adventures.”

There are perhaps parallels with Madonna in the early days, except that according to Esteban, “Lizzy never wanted to be famous and rich. But she always had a very tough relationship with men because she was a tough cookie.”

In the context of other female artists at the time, Goldman sees her as “this crazy will-o’-the-wisp chick who charmed all these more powerful artists, because it was a boy’s playground. Not like The Raincoats and people like that who were more raggedy, she was a beautiful girl in Les Halles, she was spotted by a groovy face from across the way, she got a Prince Charming and she got whisked away, as opposed to us scrappy punks.”

Clearly she was pretty charming herself, though – surely she would have found her path anyway, one way or another?

“Very good point. Because she was a talent, she had a look. So people out there looking for someone to do business with, make some money with, let alone shag… her timing was good. I guess now she might be using the internet in different ways but I guess with her set of quite organic skills she was more an arty type than a programming type. And it was when women were starting to be slightly freer, she did benefit from punk.”

Esteban refuses to be nostalgic for the period – “New York was almost bankrupt and it was possible to live cheaply downtown but you never made any money! You got 50 bucks for playing CBGBs. Any moment has its own particular things” – except for one aspect of the business: labels could afford to and did take a risk on artists like Descloux. She was able to follow her passions, sometimes riding her luck, often making her own. A couple of months after completing Press Color, the pair were already thinking about the second album “and we got an advance from a major label.” Island Records’ Chris Blackwell agreed to pay for the sessions at Compass Point, and it was next stop the Bahamas. Lizzy was on the move again.