The Dentist (for it was once a dental surgery, and still has the old signage to prove it) is at 33 Chatsworth Road. A vegetarian dinner has been prepared, there’s Wi-Fi but no heating, and from the room the interview is conducted in we can see the gig space downstairs through a sizeable hole in the floor. Léonore Boulanger and her band love everything about it. The conversation is soundtracked by support act Ebenezer’s soundcheck, and curtailed when a bit of shuffling to accommodate new arrivals in the room appears to set off a siren. It’s a familiar sound but I struggle for a moment to remember where I’ve heard it before. Then it clicks: somewhere in the room a telephone has been knocked off the hook.

Sholto Dobie, who I first encountered booking magical nights at the Laughing Bell – an obscure location in South-East London – has moved north for the Muckle Mouth series at The Dentist (also featuring the likes of Alasdair Roberts, Laura Cannell, Aine O’Dwyer and Rhodri Davis) and invited Léonore Boulanger following a recommendation by Eric Chenaux. It’s the first gig in the UK for the band (and they are very much a band), although guitarist and Léonore’s partner Jean-Daniel Botta tells me before the interview proper that he once played with a jazz group in a village in Ireland and found himself temporarily shunned by the locals; virtually abandoned without food in their lodgings, they’d tucked into the only edible thing to hand – a wedding cake that, for traditional reasons, had been left untouched on a shelf.

On their third album together, Feigen Feigen (feigen is German for figs) the trio of Boulanger, Botta and drummer Laurent Sériès have let their fecund imaginations loose in the most delightful fashion. 2013’s Square Ouh La La, had already gone way beyond merely testing the stylistic and geographical boundaries of French chanson, but Feigen Feigen (released on the Le Saule label which the band run and which also released Gaspar Claus’s album with Marion Cousin) is even more peculiar and unruly, but also more robust and curiously catchy, with clanking percussion that recalls the post-Swordfishtrombones Tom Waits and a melodic sensibility that’s like an (il)logical expansion of French cult heroes Holden’s final album Sidération. As with an artist like Brigitte Fontaine, it begs the question of how far chanson can go while still being considered as such; perhaps it remains so only in the fact that chanson was the point of departure.

Léonore, the albums bear your name but you’re really all equal partners in a group?

Léonore Boulanger: Yes, like a group.

Jean-Daniel, you come from a jazz background?

Jean-Daniel Botta: Yes it’s true but I escaped from it, almost like escaping from a prison… maybe that’s a bit strong but I found jazz to be very closed.

Even very free jazz?

J-D B: Yes paradoxically, playing jazz I felt somewhat bridled whereas working in chanson, which in theory is much more enclosed, everything explodes in terms of freedom of expression.

Laurent, what were you doing before this?

Laurent Sériès: I was a cyclist.

Is there a link between the two?

LS: Errr, no.

LB: He was freestyle BMX champion of France and Europe.

LS: When I was 18, 20.

J-D B: That said there is a link between what you’re able to do today, with your arms, an acrobatic approach.

LB: We have a song called ‘Shiva Gris’, and after a gig someone came up to Laurent and said “You’re the Shiva!”

And your background Léonore?

LB: Well I met Jean-Daniel when I was taking jazz singing lessons. I wasn’t really a musician, I was mostly involved with theatre. There was a show at the end of the year and Jean-Daniel came with his upright bass and accompanied me. After that, Jean-Daniel introduced me to Laurent.

J-D B: We started working together and it became ‘Léonore Boulanger’ because she wrote the words, I wrote some of the music and then we arranged it all together. But because it was her words and her voice we didn’t look for a name. The Eagles was already taken! But Léonore, you studied improvised music, Iranian singing… jazz was just a starting point.

Was it difficult finding your place in the French musical landscape?

J-D B: In the beginning we were making full on French chanson, old-style.

LB: Inspired by Barbara. I really like the songs in Jean-Luc Godard’s films as well, Jeanne Moreau… It was almost in the waltz tradition. I could only hear waltz-time, every time I came up with a melody.

J-D B: It’s surprising, because on the first album we recorded, which we never released and which was a sort of index of all the references we liked at the time, it was as if by doing that we put all the things we liked in a cupboard and said, “OK, that’s done, we can close the door now and start making music.”

LB: And we spoke a bit about Brigitte Fontaine, which is a reference that we get a bit too often, but it’s true that I had listened to her a lot, but once I started making music I didn’t really think about her any more. That said, I hadn’t really grasped all the things going on in her music, the rhythms of the Maghreb or the more free jazz aspects.

J-D B: And I really feel that Feigen Feigen doesn’t sound like Brigitte Fontaine at all.

It’s more in the spirit than anything else I think. Now there’s a bit of a family of musicians in France who have some of these traits in common

J-D B: Yes, we’re associated with Arlt, Mocke.

Léonore, you’re releasing a record of Persian songs for Okraina records with your teacher Maam-Li Merati soon. These new influences, did they come in immediately once you’d closed the door on the more traditional chanson style?

JD B: The first album to really have a sort of personality of its own was Les Pointes Et Les Detours, which still has one foot in a kind of French impressionism, Ravel and Debussy, particularly thanks to the pianist Alexandre (Saada), and I’d been a trip to Africa which… well it’s the same for everyone really, when you go there… so it’s quite focused on Africa that one, the guitar, which is influenced by things like Ali Farka Touré.

Then Square Ouh La La is more those Iranian rhythms. But I guess it’s an album that could seem a bit serious, because I think we treated the folk influences with excessive reverence. But now we’re freed up because this music, we love it and respect it, and we’re not scared now to behave like little imbeciles, like thugs, to play with it and mingle it with experimental or contemporary music. We’re more like kids now. And Laurent has completely deconstructed the traditional drum kit.

Literally?

LS: Yes! It’s not a drum kit at all, it’s percussion, anything I can make sounds with.

LB: There are found objects, bits of scrap metal…

LS: Bells, klaxons.

It sounds more mechanical

J-D B: When we first imagined the sleeve of the album, we actually pictured mechanical parts combined with fruit, something a little tropical.

On that subject, let’s talk about figs. The sample on the song ‘Toquade’ was recorded in Germany I believe.

LB: Yes so the sample is of a fig-seller in the Turkish market, selling exotic fruit and singing this song in a cold country.

J-D B: And then when you think of figs they’re a totally bizarre fruit. It looks a certain way but you open it up and there’s this constellation inside.

So it’s bringing something unusual from far away into a new landscape.

J-D B: Yes, that’s what we do with our music, we import little things from here and there. And then the repeated refrain “feigen feigen”, that echo, had something of a shepherd’s call, as if instead of rounding up creatures he’s rounding up figs. I dunno, he’s calling his army of figs to order. But I’m rambling a bit now…

LB: Well he’s saying that because there were points on the album where we said we could sing parts like they were shepherd’s calls [laughs].

JD B: We deliberately sang semitones, which can feel harsh sometimes, but since the melodies are quite generous and energetic it works. And on this album we really wanted choruses you know, we wanted it to be popular music. Sometimes I said it was as if we’d dressed a little pop soldier…

A pop soldier?

LB: You’re thinking maybe of Sgt. Pepper’s… [laughs]

J-D B: Well you know if mainstream pop is like an army and the rhythm of pop is ‘boom-chi’, it’s like a march. Whereas our solder, called Feigen Feigen – it’s strange because his first name is the same as his surname – instead of marching normally, he makes strange gestures ( at this point Jean-Daniel nearly falls off his chair demonstrating the gestures). That would be a good end to the interview, me falling through the floor! But yes he has the appearance of pop, but not its movements.

It must be a complicated process assembling each song?

J-D B: Yes, very. It’s complicated and takes a long time. Especially this latest one.

LB: There’s a lot of playing around with deconstructing the songs. Sometimes we say it’s a bit like that Chinese puzzle, the tangram, or a Rubik’s Cube, because we have to somehow fit the mechanism together.

J-D B: We actually had a first attempt at recording the album with a choir, but we weren’t happy with the results.

LB: Originally we’d wanted to do it with an African choir, as Jean-Daniel and I had been to Abidjan, to a music school there, and we’d started to work on the first song on the album, ‘Bluette’, there so the dream was to go back and record it at the school, because they got all the harmonies immediately.

J-D B: But it was too difficult financially, we’d have spent more time chasing grants than working on the music. So I said stop.

LB: And we had to find a new musical setting for this record. So since we couldn’t go to Africa we went to Berlin! And we thought that maybe a choir could record with us, and we tried it with Swedish musicians but we had too little time with them to come up with something satisfactory. In fact we were so dissatisfied we thought that maybe it was the songs themselves that weren’t up to scratch and that we’d have to start again. So we found a new space… because it’s often that, you know, making a space your own, finding the right sound. We ended up in a house in Poitou that was a bit magical, full of old mirrors and typewriters, rusty metal drums and de-tuned pianos.

J-D B: The real key for me was the pianos, because I re-transcribed quite a few of my guitar parts for piano and then showed them to Laurent because he plays piano, and it was Laurent who made the discovery of the drums – it was him who brought this abrasive quality. And these out-of-tune pianos were wonderful. You know, I like people who have one eye lower than the other.

Most people have that!

J-D B: I think it’s really noticeable with me in photos, I’ve really got one eye here and the other down there.

LB: Like a Picasso (laughs)

J-D B: But once we were there I realised there were four songs I didn’t like at all, I spent 15 days on one song trying to sort it out, I was going crazy.

LB: And sometimes we’d leave the house and play a gig. Not always successfully given that it was all a work in progress at that point in our heads.

When you’re in that kind of headspace as well, it’s not easy changing mode and going out into the world.

J-D B: No it was really hard, we messed up a few gigs! It’s like a snake that is still part-way through shedding its skin. And this house is a bit hidden away, it’s called Chantecorps (literally ‘the body that sings’).

Seriously, you haven’t made this place up?

J-D B: [Laughs] Yes, there’s an old lady who lets us use the house.

LB: At one point I heard noises in the garden and went outside and I was like “there’s techno in the garden”. And it was the guy who owned the land near the house who had a let a techno group come along and play. It was great so I recorded it and that features at the end of the track called ‘Minuit’.

There are a number of field recordings on the album

J-D B: Yes and we couldn’t record the songs in one take because there were so many new ideas coming and complicated rhythms, so we always recorded live but it would just be a section, so there’s a lot of editing.

That editing process is raised explicitly on ‘Toquade’ where there’s a recording of Léonore saying, “I have a technical question, if one of us makes a mistake and it doesn’t bleed into the other microphones is it possible to just cut…” just before there is an actual cut in the track. And as you repeat it later it also acts as a kind of chorus or hook.

LB: Actually that’s not me, it’s the voice of Gunhild Anderson who’s a Swedish singer we toured with over there. But it’s what’s left over from the aborted first session for the album.

J-D B: When I listened to it, it fitted so well with the rhythm… I mean what we look for, I guess what all musicians look for, is when the music comes to you by itself, without you having to do anything to make it happen. Like when we heard the fig-seller, there was already music in that, he gave us the desire to write a song. So that phrase, when I heard it I said, “That’s music.” Just one sentence, after a week of work, and in the end that was all that was worth keeping. But it’s great, because the way she says it there’s a groove to it.

Léonore, on the album you sing in a variety of languages – French, German, what else?

LB: There’s a little bit of Persian, but it’s a less serious approach to the record with Maam-Li Merati, and then there’s a little bit of invented language as well. We’d already enjoyed playing with Germanic sounds on that previous album, inspired by Kandinsky’s poems. And what interested me was that it was a Russian writing in German, so again it’s someone in exile, like the fig-seller singing in German but putting a bit of Turkish in there too. I like that thing of language escaping you, and I sing a lot in foreign languages even though I don’t speak them very well. But even in French it happens to me that I can’t find my words.

J-D B: And sometimes when you sing a song in a foreign language, you have a vague idea of what it’s about but you complete the meaning with your own imagination.

LB: Words become magical, like incantations.

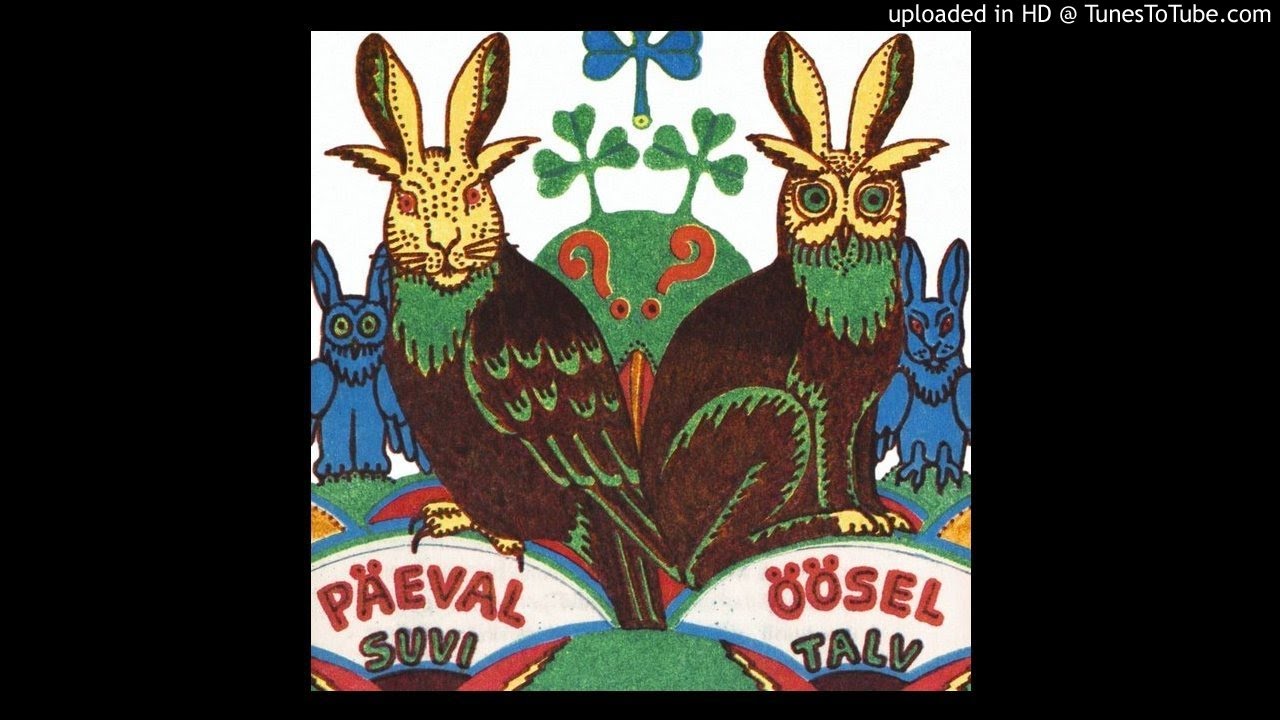

The sleeve illustration is very striking, with these hybrid creatures and the peculiar kind of fertility they suggest.

LB: It’s true, people have said to us that to us that it’s as if we’re creating our own folklore. And with the sleeve of the album, which comes from the work of an Estonian illustrator Vello Vinn, there’s something of Lewis Carroll, as if you’ve opened a door onto a world that’s wonderful and unsettling. But it’s also the idea that the supernatural or the fantastical is there just in the margins of daily experience.

This idea of creating your own folklore, does it just apply to the music or is it something that also helps you live from day to day.

J-D B: For me, personally, this record helps me to live. When we play, all my cells immediately align. When you’re making music or involved in any kind of craft, it’s about finding gestures that really belong to you. And with the music we’re playing now, I feel really good with it, I feel the gestures fit me.

LB: But the question was about creating your own landscape as well, your own country.

J-D B: Well the thing is we toured with American musicians, and when they get on stage they were really… American, you know super entertaining, it was entertainment. And for us because we’re not like that we really needed to create something strange so that when we’re on stage it immediately gives us a kind of strength. By making this strange music we already have some… some special powers. It’s like an energy that protects us.

Rockfort Quietus Mix 5 – November 2016 Tracklisting

Delphine Dora – ‘Le Mystère Demeure’ (Bezirk)

Léonore Boulanger – ‘Toquade’ (Le Saule/Ana Ott)

Eve Risser & White Desert Orchestra – ‘Eclats’ (Clean Feed)

Theoreme – ‘Moyen Age’ (Bruit Direct)

Agar Agar – ‘Symbiose’ (Cracki)

Cléa Vincent – ‘Château Perdu’ (Château Perdu /Midnight Special)

Rubin Steiner – ‘Pink Wave’ (Platinum)

Night Riders – ‘Mauvais Rêve’ (Passion Vinyle)

Jonathan Fitoussi – ‘Aquarius’ (Further Records)

Paulie Jan – ‘Phase VII’ (Tripalium Corp)

Ply – ‘Sans Cesse’ (Warm)

Formal Regression – Rétrovision (Hylé Tapes)

Julien Gasc – ‘L’œil’ (Born Bad)