This month there are two shows coming up at Cafe OTO that I’ve had a hand in organising: on 19 October you’ll find the darkly gleaming delights of Rien Virgule, who some might have caught on Tusk TV earlier in the year and whose La Consolation Des Violettes was one of tQ’s 100 best albums of 2021, paired with freak-chanson duo Arlt, while on 23 October, a triple bill includes one of France’s most singular guitarists, Mocke, Léonore Boulanger’s fractured song-craft and Breton bagpipe-player Erwan Keravec.

And, not at all coincidentally, both Keravec and Boulanger are also releasing splendid new albums. The Rockfort mix above features music from both, alongside tracks from rapper LELEEE – featured in the last column and back with another, intensely fried collaborative release with beatmaker Avddxct called simply .; a lustrous cut from sound sculptor Mathias Delplanque’s latest, Ô Seuil, superb industrial sounds from duo À Travers’ album Bostrophedon, the Billie Eilish-on-mushrooms pop of UTO; an excerpt from Sourdure’s soundtrack to Sébastien Betbeder’s Alpine drama Debout Sur La Montagne; French pianist Eve Risser and her Red Desert Orchestra (reviewed here) and finally something from the very exciting collaboration between rapper Lala &ce and producer Low Jack that I’ll be covering in much more detail soon…

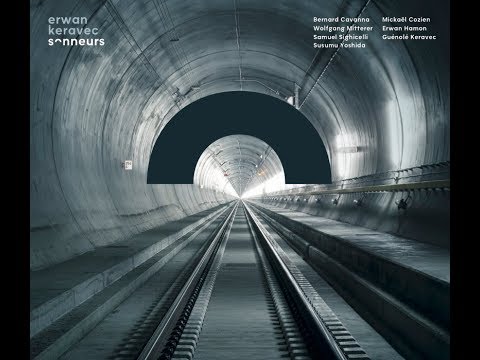

I first encountered Keravec at the Unsound festival in Krakow in 2019, performing rapid-fire salvos for a rapt audience on the dancefloor of Hotel Forum in Krakow, so you won’t be surprised to learn that there’s nothing straightforwardly trad about his approach to the ‘pipes. Keravec is Breton and plays Scottish-style bagpipes, a late 19th century import to the region and more elaborate than the smaller, traditional biniou kozh. The La Nòvia collective are fellow travellers to the extent that they have connected the dots between minimalism and folk (and drone-producing instruments like the bagpipe and the hurdy-gurdy), but while they mostly take traditional folk songs as jumping-off points, Keravec’s primary focus these days is contemporary composition. On Sonneurs 2 he tackles pieces by Philip Glass (‘Music In Similar Motion’) and Dror Feiler as well as compatriots Pierre-Yves Macé, Frédéric Aurier and Jessica Ekomane – her piece was written during lockdown especially for Keravec and his group of ‘sonneurs’ – meaning ‘players’ and more specifically the French term given to traditional Breton musicians – of various types of bagpipe and bombarde (a double-reed woodwind instrument).

These two types of instruments together provide Breton music with its drones and bristly, piercing top end, and are exploited to the full over the nine pieces here. Macé’s shorter ‘Five Dolly Shots’ pieces, such as bracing opener ‘(re)commencer’ with its upwards sweeps and unison trills, punctuate the longer works; Glass’s arpeggios are refreshed by the approach, but Ekomane’s ‘Latitudes’ stands out with its breath work, interjections like car horns or lowing cattle and gleaming electronics, while for Aurier’s ‘Antienne Pour Les Jours De Fièvre’, Keravec has called on the services of the Quatuor Béla, a string quartet, who open the piece with seasick swells, and help to deliver a majestic, thumping climax.

The fifth album from Léonore Boulanger, Jean-Daniel Botta and percussionist Laurent Sériès sees them “composing and decomposing” the so-called art brut poetry of Austrian Ernst Herbeck, who was born in 1920 with a cleft lip, jaw and palate and hospitalised after World War II due to his apparent schizophrenia; he eventually wrote thousands of poems, frequently as a response to prompts from his psychiatrist Leo Navratil. However, it’s not an unsavoury fixation on Herbeck’s struggles or his ‘madness’ that seems to have motivated Boulanger and Botta on Un Lièvre Était Un Très Cher Baiser but the vivid, compressed flashes of the poetry itself acting as a spur to their own creativity. Beyond simply providing a musical backdrop for the words, which are sung by Boulanger and Botta in their original German, they’ve gathered the nursery-rhyme cadences and enigmatic imagery of Herbeck’s poetry and their own sense of phrasing and diverse instrumental resources into a series of unique, strange and joyous gestures. As on previous album, Practice Chanter, the results are recognisable as songs, but are frequently also as circuitous, tangential and tangled as thought processes. Weaving your way through, you’ll also find new ingredients this time, like what sounds like cruise-ship synths, a Linn LM-1 drum machine (the one favoured by Prince in the 80s) on ‘Der Tanzbar’ and ‘Schlaf, Mein Gehirn Schlaf’, a lolloping sort of 80s club jam beat for ‘Der Traum & Der Regenbogen’, and is that Auto-Tune for a section of ‘Das Schweigen’? ‘Der Patient’, with its jolly synth-brass parps and mewling cat noises, encapsulates the giddy pleasures on offer.

In 2018, in a case of greatness recognising greatness, Alpha Wann’s instant classic ‘Ça Va Ensemble’ included the line “Laisse-moi rapper comme Lavokato ou le Prince Waly” – “Let me rap like Lavokato (half of duo Les 10’) or Prince Waly”. Buti in 2022, Prince Waly, a rapper from the Parisian suburb of Montreuil (in the Seine-Saint Denis suburb aka the ‘93’ (PLEASE INSERT LINK https://thequietus.com/articles/29982-sourdure-gazo-heimat-sch-french-music) and whose career began around a decade ago, has just released his debut album proper, Moussa and is dropping lyrics like “Now I’ve been making rap for a long time/where’s the recognition/I feel as though I’m being forgotten.” What happened in the interim is that Waly faced a cancer diagnosis – chemotherapy is mentioned explicitly on closer ‘Mercy’, while ‘Broke’ and ‘Miroir’ are brutal assessments of an attendant loss of self-confidence. The counterweight to the introspection, though, is the complete artistic assurance displayed on Moussa: a huskiness has been added to his easy technicality and instantly recognisable, nasal twang – most likely an American influence but which occasionally makes him sound a little like he’s from Perpignan rather than Paris; as a statement, it’s a lean, perfectly sequenced self-portrait that also finds space for some classic storytelling (‘Movie’), a hypnotic collaboration with Freeze Corleone on ‘Balotelli’ and the deliciously shuffle of ‘Problème’ with Luidji and Makala. Judging by the response in France to Moussa, Prince Waly no longer has any reason to fear being a relic of the past.

Yes, Super Parquet! Perhaps feeling that their already mammoth debut album of maximalist minimalism and bastard folk wasn’t weighty enough, the Clermont Ferrand-based four-piece have returned with a monumental double album, a techno-folk Use Your Illusion of sorts. And, as I pointed out last time, the fact that they make the combination of folk instrumentation (banjo, Auvergnat bagpipe, drone boxes etc) and ‘beats’ sound like the most natural, rather than the cheesiest, thing in the world is almost miraculous. The first album, Couteau is the more direct and song-based of the two, from the electric jolt of the title track, via the frolicking synth squiggles, clattering beats and rumbunctious, amplified cabrette on ‘Sumatra’ and the rippling banjo trance of ‘Adieu Privas’. Haute Forme extends their sound further, into two stunning, nearly 20-minute-long pieces suggesting a rural vision which, far from being antediluvian, includes farm machinery, the rhythms of harvesting and threshing.

The last time round, on Vie Future, La Féline’s Agnès Gayraud explored a cycle of death and birth, prompted by the death of her father and the arrival of a son. On Tarbes, the subject is the provincial town in the south-west of France, in the Hautes-Pyrénées, where she grew up. There’s another cycle here – on the first La Féline album, Adieu L’Enfance, Gayraud was leaving childhood behind; here she’s viewing at it, and her hometown, from a new perspective, that of a revenant, perhaps, shadowing her teenage self, on the trail of truths she may have missed at the time: “I haven’t been back to Tarbes in some time”, she begins. The clipped disco pulse of ‘Je Dansais Allongée’ most closely resembles the ‘bedroom pop’ of Adieu L’Enfance, which is fitting since it’s about dancing lying down “on my unmade bed” after a night on the town and falling asleep with make-up still on. Elsewhere, though, the presence of new recruits – drummer François Virot and guitarist Mocke – is felt in the greater sense of space and spontaneity in songs like ‘Va Pas Sur Les Quais De L’Adour’, which the latter adorns with solos that sit somewhere between Robert Fripp and Ali Farka Touré. Tarbes sees Gayraud further refining her ability to deliver gut-punches couched in elegant, erudite pop. Songs like ‘Le Garçon Sur Le Toit’, with its supple grooves and swirling synth washes, don’t demand your attention; they slip your defences and slowly overwhelm you from the inside.

Fans of Senyawa will find plenty to admire in Nze Nze. While the former thrust Indonesian folklore into a fearsome, post-industrial setting, the French three-piece take the warrior songs of the Fang, a Bantu people based in Central Africa, weld them to thunderous beats and drown them in echo. French vocalist Mathieu Ruben N’Dongo, whose father comes from the region (and who also records as Coldgeist and Sacred Lodge) has teamed up with the two members of duo UVB-76 (Gaëtan Bizien and Tioma Tchoulanov). They share a common attraction to the places where post punk, industrial, dub and ritual African rhythms meet, and Adzi Akal (‘eat the metal’) is the thrilling outcome. The trio are at full pelt on ‘A Kele Nkoo Oking’, which provides a juddering platform for N’Dongo to unleash his range of throaty whispers, low whoops and guttural growling, while a barrage of jackhammer beats rains down on ‘Yemendzine’s insistent motorik-punk groove, but there are more measured, atmospheric moments to savour too, like the rustle and harp twang of opener ‘Odzamboga’, and ‘Oku’ with its slippery rhythm that feels like it’s been constructed out of wet logs.

Scaring The Mice For Revenge is a great album title from the more prosaically named quartet of Shane Aspegren/Nicolas Laureau/Jérôme Lorichon/Quentin Rollet. It’s an in-house formation of musicians from the Prohibited label, founded by the Laureau brothers (NLF3), with Lorichon and Aspergen members of The Berg Sans Nipple, while sax player Rollet has played with the likes of Red Krayola and Nurse With Wound. Their particularly timely notion was to revive the “Hindu-tinged spiritual jazz of Pharoah Sanders and Alice Coltrane”, with the clearest signifier being Laureau’s sitar. There’s undoubtedly a scent of patchouli on the five pieces here but otherwise this is far from a retread or a pastiche. The four-piece have a distinct identity of their own – there’s a free improv-informed close attention to sound-in-itself, but it’s all tied together by Aspegren’s springy, circular grooves and the use of electronic effects, particularly in ‘Charming A Snake Pit’s’ stuttery, ear-drum fluttering closing passage. Despite the lack of an obvious bass instrument, ‘Tsetse’ essays a drowsy sort of funk that’s run through with sax moans, breaths, electronic scraping and a decayed, three-note sitar figure.

I came across Roxane Métayer’s work last year with the delightful Éclipse Des Ocelles , which saw the Brussels-based French visual artist and violin plater fold field recordings and treated-and-looped violin into each other to sublime effect. Visage Zygène, a title which is linked to a type of butterfly, is a less ethereal but more vivacious and playfully spacialised – on ‘Poisson D’Argent’, the sounds of plucked and tap string are sucked backwards and squirm around inside the stereo space, ‘Blanc De Lune’ features a rhythm made effected breaths, tinkling and trickling percussion and a rushes of flute that billow that streamers in the air. In the way she juxtaposes the different instrumental elements, Métayer evokes nature as a space in which multiple, and sometimes minute, processes are happening side-by-side, affecting and interacting with each other but also following their own peculiar logic.

And speaking of natural processes, Jean-Baptiste Geoffroy’s head-scrambling Porous Talk sounds like chattering synth noise (or occasionally, the sound I make with my mouth when I’m pondering something tricky), but is actually recordings of what happens when chalk, terracotta and freestone are dunked into water – Geoffroy calls the tracks ‘porous talks’, the rocks chattering away as they release air they contain.

Quietus Mix 32

Super Parquet – ‘Couteau’ (Airfono Records)

La Féline – ‘Solazur’ (Kwaidan)

Mathias Delplanque – ‘Seuil 2’ (Ici D’Ailleurs)

À Travers – ‘Ripsylve’ (Zamzamrec)

Nze Nze – ‘A Kele Nkoo Oking’ (Teenage Menopause)

UTO – ‘Steps In The Dark’ (InFiné)

Prince Waly – ‘Avertisseurs Part II’ (BO Y Z)

Lala &ce & Low Jack ft Le Diouck, Rad Cartier – ‘Gelati’ (PAN)

LELEEE & Avddxct – ‘Audio Crack’ (Blooody Record)

Léonore Boulanger & Jean-Daniel Botta – ‘Das Schweigen’ (Slouch Hat/Le Saule)

Roxane Métayer – ‘Poisson d’Argent’ (Wabi Sabi Tapes)

Shane Aspegren/Nicolas Laureau/Jérôme Lorichon/Quentin Rollet – ‘Cow Face Posturing’

Erwan Keravec – ‘Five Dolly Shots – Torsion’ (Buda Musique)

Jean-Baptiste Geoffroy – ‘A-6’ (Minimal Resource Manipulation)

Sourdure – ‘Romanche’ (Three: Four Records)

Eve Risser Red Desert Orchestra – ‘SO (Horse)’ (Clean Feed/Orkhestrâ)