Click here to read the rest of the Electro Chaabi In Cairo series

We’re staying in the Mayfair Hotel off July 26 Street, situated on an island in the Nile. It has a large colonial entrance hall and a once grand marble staircase that speaks of different distant times while inside, sub, sub-divided rooms with rickety wardrobes, monastic beds and hopeful electrical wiring speak to a more realistic, pragmatic present. Outside in the very welcome Egyptian sunshine the beeping horns continue apace. These sounds are the permanent punctuation of the trip. In fact, just presume that they making their presence felt constantly from this point onward, unless I say otherwise.

In sustainability terms, Cairo is a very big wake-up call to the West. Everything we have – roads, buildings, cars, fresh food, pets, bridges, donkeys… urban space itself – we could get a hell of a lot more out of it if we wanted to. And while no one could make a solid case for Cairo in totality being a beautiful city, it is shot through with ravishing and breathtaking detail. Razor slashes of vivid green line the Nile, cool palm tree lined avenues, beautiful mosques. And, of course, if you love concrete – well, this is a place you have to visit.

The people are extremely friendly – probably the friendliest strangers I’ve ever met – and bid you welcome from doorways and moving cars. Men blow me kisses and children want to talk football and dancing. They are courteous and helpful to a fault. Now more than ever, people should be watching what they say about lumping all Islamic peoples in together. Egypt makes a mockery of the heinous Orientalist idea that all Islamic people are somehow out to get us. Five Egyptian pounds seems to be the tourist tax on literally everything you buy on the streets, no matter what it is, but as this works out at about 50 pence and is always delivered with a smile and sometimes with an exhortation of "David Beckham!", only an idiot would moan. On an unrelated note, Julie Burchill should try coming here on her holidays, she’d probably love it.

Joost and I don’t have much Arabic. During one attempt to buy falafel, I end up with an aubergine chilli, four falafel pittas, a bag of pickled vegetables and a crisp sandwich. It is all lovely and comes to exactly five Egyptian pounds. Even though I’d find it hard to explain why, while I’m standing on a bridge over the Nile, the sight of a food delivery guy on a moped, carrying a huge tagine over the back wheel instead of a box containing pizzas, cracks me up tremendously.

Music is of near-primary importance in the Arab world, and Cairo is where its central nervous system stems from. There is a saying which claims all Arabs can only agree on two things: Allah and the importance of Cairene singer Umm Kulthum – known as Kawkab al-Sharq, or The Star Of The East. There are many baroque stories attached to her emotionally resonant talent, such as a habit of gulping down lung bursting draws of hashish before each performance and wearing a shawl steeped in opium which she would inhale from while singing. She was President Nasser’s key weapon in unifying various Arab tribes, and political speeches had to be timed carefully as to not clash with her concerts. She died in 1975 but still to this day, at 10pm on the first Thursday of every month, all Egyptian radio stations play nothing but her music. According to Egyptian music experts David Lodge and Bill Badley, Israeli radio stations still try and seduce Palestinian listeners by playing her music, mixed in with propaganda. So perhaps comparing Western music to Egyptian music is a bit of a fool’s errand in a piece this short – for example, to compare Umm Kulthum to Elvis or The Beatles or whoever is to underestimate her popularity and importance here by many, many magnitudes.

Like many other countries such as Jamaica and Mali, there are as many regional musical forms here as there are in, say, the UK and America, if not more, so perhaps it’s not that surprising that word is only just spreading outside of Salam City to Cairo and the rest of Egypt about Electro Chaabi. Also, because of the way Egypt is run, this form of music doesn’t get anywhere near the radio – it is distributed currently for free, via Facebook and Mediafire files. The MP3s act as advertising for parties. However, as with most new forms, it hasn’t sprung fully formed out of nowhere. Chaabi (or Shaabi or Sha3by or Cha’abi depending on your transliteration) may have little to do with the classic Arab vocal tradition, but it has strong late 20th century roots in Egyptian working class culture.

In class terms it’s had an odd history, starting off as a middle class folk revival of sorts. The style of "light song" was a direct response to the humiliating defeat of the nation by Israel in 1967, and was an attempt to reinvigorate dented Egyptian pride by promoting national feeling via folklore and folk music. Shaabi singers specialised in an improvised vocal performance called the mawal and originally the aim was to move the listener with the most heart-rending performance possible. As time moved on however, it became a lower class phenomenon, turning more ribald and celebratory, with faster rhythms that suited exuberant working class weddings and down town nightclubs. The links with an earlier folk culture became more real and direct, meaning the lyrics could be, relatively speaking, earthy and suggestive. Again, according to David Lodge and Bill Badley the lyrics to one song, "Her waist is like the neck of a violin, I used to enjoy apricots but now I would die for mangoes", made it a massive underground hit with Cairo’s gay community. This innuendo, as innocent as it may seem now, was quite outrageous in its day, and did not go down well at all with more conservative Islamic elements in the city.

This outrage-courting sensibility is carried on today. One of Electro Chaabi’s biggest dance floor fillers, and reputedly Egypt’s first ever song with swearing in the title is called ‘Aha el shibshib daa!’ or ‘Fuck! I’ve Lost My Slipper!’ by producer Amr 7a7a (pronounced Amrir Ha Ha), DJ Figo and ‘mic man’ Sadat. These are the three guys who started the scene five years ago. It was such a small concern that it was pretty much only them until two years ago but now, post-revolution, it is blossoming into something bigger. And as Joost and I have learned from talking to people we’ve met, it appears to be becoming more acceptable once again among more adventurous middle class types. As I’ve said before, it’s impossible not to look at this music in terms of the Arab Spring, given that it has happened at the same time. But in a lot of ways, the celebratory lyrics and party tunes act as a relief for people from having to think about the revolution. For some people this music is their safety valve. (This is not to say that there isn’t a revolutionary aspect to some of the music, but more on this later…)

Through Joost’s efforts as part of his Tilburg based DJ collective Cairo Liberation Front [check out their Soundcloud page for mixtapes], in getting in touch with all of the scene’s DJs, producers and MCs, we’ve been invited to Electro Chaabi’s wedding of the year. Sadat is getting married to Samer in their home town of Salam City and we’re going. I am given my instructions: "Do not kiss the women. Shake their hands. If someone offers you a glass of water drink it immediately and give the glass back and ask if you can say congratulations to the parents. And say you’re Christian if anyone asks your religion."

We have to go through some old school rave shenanigans to get there, but this just adds to the excitement. At 4pm we take a cab to a roundabout in Maandi and the cabbie calls Noov, Sadat’s manager. She then takes us via a second cab ride to another pick-up point, where a man called Sherif drives us out of Cairo past shanty towns, ancient stone buildings and suburbs to Salam City itself.

Noov and Sherif are excellent hosts. They are, it’s fair to say, more middle class than anyone else in attendance. Noov is not only Sadat’s manager but she is a lawyer for the Egyptian Organization For Human Rights, and has been involved in media monitoring and research projects into the torture of women. They are not fixers. No baksheesh changes hands. They are helping us purely because they see the massive potential in Electro Chaabi… not just for bad-ass partying, but for the massive social and political potential it has as well.

I’m here to write about music, and it’s perhaps not the best time for Western journalists to be asking about the revolution (for the sake of interviewee and interviewer), but at the same time music has never existed in a vacuum anywhere – least of all here. I ask, gingerly: how are things for women now? She winces and shakes her head.

I explain that I don’t want to talk about stuff that’s going to get anyone into trouble. She says simply: "I can’t speak for anyone else. As an individual I can say things are worse than ever for women. Under Hosni Mubarak? That was as good as it got. It’s best that we talk about music."

The car goes silent until a crazy-sounding Arabic interpretation of Queen’s ‘We Will Rock You’ comes on the radio. Noov jokes: "If you want new music in Egypt, just take something old and make something new out of it."

She starts telling us about the music that we will hear, what will happen at the party and why this particular party is so significant: "The music is called Electro Shaabi because it is electronic and it is played in the streets. The style of music is also known as festival music or ‘mahraganat’ music. I have been to many weddings, but tonight will be the best wedding of all. Every singer and producer will be there. You are lucky. You can’t hear their music on the radio. People find it strange. But it is popular, and you have to give it a chance. It is still only really known in Salaam City and two nearby neighbourhoods."

Finally, after hours of driving, we know when we’re getting close, because we start following a souped up micro-bus with a Bob Marley poster in the rear window blasting out beats. We pull over at the roadside near some parked cars, a row of motorbikes and a drinks stand. As soon as we step out of the car we are greeted warmly by Sadat wearing a sharp suit. He grins wildly as he dances in front of the car he is picking up for the event. Friends with camera phones capture his sharp moves as boys do stunts on BMXs and teens pull wheelies on motorbikes up and down the strip. Everything is souped-up. Buses, micro-buses, nano-buses, Ladas, motorbikes and one flash BMW. Everything is under-lit with neon. There are expensive looking speaker systems on even the mopeds.

The Bob Marley bus has its back door open. It’s blasting something based round a Nelly loop, but with sampled tablas and harsh synths. As Noov said: if you want something new in Egypt, build it on something old. Three tunes are playing at once, everyone has to work their horns harder to make them heard over everyone else’s. It’s like being pleasantly broiled in a cauldron of sound.

A huge squealing of tyres from the open-topped wedding car containing Sadat and Samer signals that it’s time for the convoy to set off for the party. There is the smell of superheated rubber and burning tarmac as plumes of dust and smoke rise into the air. We set off, en masse, into the already-packed streets.

The first junction that we arrive at has no lights, and the situation becomes comically insane. The gridlock seems to last forever, with people only willing to use their horns to negotiate a way through it. The staccato deployment of car horns becomes just one long, uninterrupted roar. Everyone in our party starts using very complex, very loud musical horns, people lean out of windows with air horns, blazing car stereo systems are turned up to maximum. Joost is laughing incredulously. He points at my Sunn O))) T shirt. We both start laughing hysterically. (Before I came here one of the people I spoke to was a dude called Hicham Chadly from the record label Nashazphone, who put on Sunn O)))’s first ever gig in Paris, and is also releasing Islam Chipsy’s first music outside of Egypt on a compilation. He also knows members of Egypt/American based Sun City Girls, but says that Chipsy’s music is the most mind-blowing he’s been involved with. Perhaps deep down there’s a link there somewhere.)

The vehicular procession is something to behold. Excitable young men ghost-ride the whip next to rolling cars. Bikes zip in and out of traffic trying to get the closest to the wedding car. The couple’s official photographer stands on the bonnet of their moving convertible, snapping away at them. People climb out of the windows of a micro bus and up onto its roof as it takes a corner. The passengers of one bus are dancing so hard inside that it appears to have hydraulic suspension, which it clearly actually doesn’t.

"This is the thing about countries where no one drinks" says Joost soberly. "They really know how to have fun."

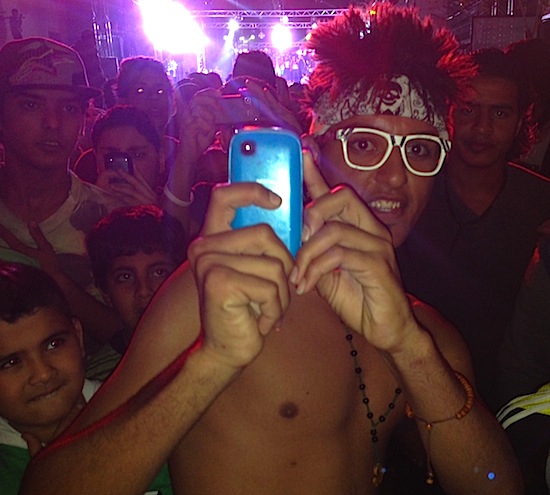

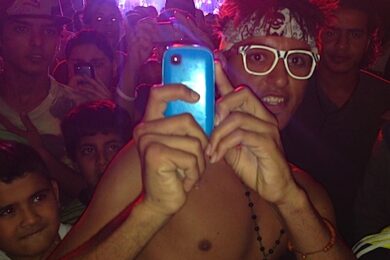

Arriving at the party proper will remain to my dying day one of the most bizarre and exciting things that has ever happened to me. The bass is overwhelming two blocks away and there is clearly a light show of some magnitude being deployed casting flashes and shadows up the sides of concrete housing blocks. On the street itself, the four of us are met by one of Sadat’s boys. He tells us to keep close and sets off through the throngs of people at a jog. We run past bonfires with young children spinning flaming torches on chains, and once through a makeshift curtain that has been used to close off a very long section of street, he must see how boggle-eyed we look as he keeps on exhorting us to, "Keep close! Keep close!" There are lights and screens erected everywhere. We pass under the stage. Even though the street is crowded everyone parts for us, rushing us through, shaking our hands, clapping us on the back. In the arena itself people are breaking out into frenzied bursts of dancing. A young man lets off a purple safety flare next to me and someone above me on a platform is using a large aerosol can and cigarette lighter as a flame thrower. We climb up next to the soundman – who is wearing a British police constable’s peaked cap – where we get a good view of the stage. There are, at any one time, about 25 people with microphones on stage, a couple of DJs and, on a precarious podium to the left, a couple of drummers. People are hanging off gantries and lamp posts, out of windows, they’re up trees and all over the roofs. Sadat is leading the MCing while busting some particularly fresh moves, but he’s not on stage long before diving off to be carried at head height across the crowd, where he then starts scaling a speaker stack. Post rave, it’s hard to imagine anything like this happening in the UK now.

I ask Noov who is on stage, and she says: "Amr 7a7a, Sadat, Alaa 50 Cent, Diesel, Filo from Alexandria, Ghandi, Figo, Zo2la and Ali Wezza." She says some other names but her and Sherif start laughing uproariously, and I’m pretty sure they’re just making them up. The only song I recognise is a cover of Akon’s ‘Smack That’ by Diesel, which you can hear at the end of the Cairo Liberation Front mix at the top of this feature.

A young guy shows me his home made gun and knife. They look ridiculous but could also certainly kill you. This is the only shady thing I see all night. Egyptians are very resourceful people, and it is the same spirit of resourcefulness that has allowed this musical scene to flourish that helped make deadly weaponry out of nothing.

After a while the four of us decide to brave the crowd. "It will be OK," I reason, "as long as I don’t lose them." The second I step into the crowd I stop to look at some men dancing and lose them.

People are letting off flares, strobes and lasers are blazing and there is unhinged dancing going off everywhere. Everyone wants me to dance and everyone wants their picture taken with me. If I was in any other place on Earth right now (especially England) I’d be terrified, but as it is I know I’m safe. These people are too proud of what they’ve done and what they have. This neighbourhood may look like a township but they are fully invested in their community and want me to know how proud they are. Men take me by the hand and clear a path through the crowd and lead me to the companions I’ve lost without me even asking. Embarrassingly, Joost and I are treated like stars ourselves. Everyone wants to have their picture taken with us and everyone wants to dance with us. It’s a pleasure and a privilege to accept all invitations.

We leave at midnight with the party still in full swing. I think Noov and Sherif can tell that Joost and I are suffering from some kind of hyper-enjoyable shell shock.

After sitting in silence in the car on the return to Cairo for some time I start laughing and can’t stop. "Oh my God. I think that might have been the most exciting thing that’s ever happened to me."