Before I get down to a couple of this month’s releases, there a couple of massive objects looming on the horizon that I need to address…

Daft Punk

When I started looking at current French music in the 90s, it was in the knowledge that this was a post-DP context, in which the horizons of French musicians appeared to have been expanded, and perceptions of the country’s musical output, particularly in the Anglo press, was starting to shift. But beyond that, as Simon Reynolds once posited, Daft Punk were emblematic of a situation in which "we are all French today… maybe that degree of twice-removed and hyper self-consciousness is our common condition."

While French rock had often been perceived as having an ersatz quality – or more plainly, as a second-rate copy of the ‘real’ thing – Daft Punk and also Air went beyond in being both French and "French" – aware of, and drawing on, the nebulous associations that for a foreigner might constitute Frenchness in music, from sophistication to naffness, hence Air’s first album bearing the legend ‘French Band’. The arrival of Daft Punk was the moment when a ‘French band’ became not just a distorted mirror held up to UK/US sounds, but to pop culture at large, where everything is within quotation marks to the degree now that we barely register their presence. This went hand-in-hand with their managing to be everything to everyone – dance act, pop duo, stadium rock band, faceless anti-band – while tearing up notions of cool and uncool influences; everything was up for grabs, the past was a playground, the canons didn’t matter. It made no sense to accuse Daft Punk of not being the ‘real’ thing since the ‘real’ thing didn’t exist any more.

Phoenix

From their 90s beginnings, while the French were still hung up on their rock groups having too many hang-ups, Phoenix insouciantly knocked out Untitled – an untidy, uneven, charming and unabashed homage to the, at that time, not-exactly hip sounds of The Eagles, Michael Jackson’s Thriller, AC/DC and Van Halen. They seemed to see their remove from these mostly American influences as a license to wear them lightly, and in that they had much more in common with Daft Punk and Air than other native rock bands. For years they seemed like prophets without honour in their own country and yet, when they tried to out-Strokes The Strokes on third album It’s Never Been Like That, a plethora of French groups like Pony Pony Run Run and Fortune moved into the white soul/funk space carved out by ‘If I Ever Feel Better’ and ‘Everything Is Everything’. Their late-70s/80s radio Eldorado also anticipated the chillwavers, the difference being that Phoenix didn’t make their music sound like a memory-mirage.

Then Phoenix broke in the US with Wolfgang Amadeus Phoenix, an album on which it seemed they’d found the essence of their sound, to the point where there was minimal difference between the actual tunes on each song. It was highly melodic album and yet somehow the melodies were as slippery as water; they all blended into one, like déjà vus (or perhaps déjà entendus) of each other.

As you are probably aware, Phoenix and Daft Punk both have new albums on the way. They’ll be reviewed everywhere, which is appropriate as both may well still have plenty to say, whether intentionally or not, about the overall state of things. For example, I’m currently mulling over the ‘Chinese’ riff to Phoenix’s ‘Entertainment’ – after successfully selling the USA back to itself, are they writing songs primed for Asian market penetration?

BDP and Sloy

BDP (Before Daft Punk), the grunge era was still very much the dark days for French music. Of course, it’s not inconceivable that there were loads of fabulous rock groups operating under the radar but Sloy were one of the very few to gain some kind of international acceptance, getting the John Peel seal of approval, a devotee in PJ Harvey and Steve Albini’s "moisture free" (said the NME) production work on two of their three albums. All three, plus two EPs, Fuse and Pop, got a digital reissue at the end of last year courtesy of French publisher Grand Blanc.

Armand Gonzalez and and Virginie Peitavi, who were two-thirds of the group and now operate under the name 69, are keen to stress that they were contemporaries of the US grunge acts, not copyists or Johnny-come-latelies. They formed in 1991, so there’s no certainly evidence of serious stylistic time-lag. Their work stands up well – loping, increasingly even funky (they claimed Talking Heads as a major influence) rust-bucket guitars, Peitavi’s prowling and growling bass, Gonzalez’s incontinent yelping, goofy TV and radio samples. Armand talks about having wanted to invent a ‘groove mécanique’. Debut album Plug is the fiercest, the last, Electrelite (without Albini) the most sonically varied, packed with bug-eyed freak rock like ‘Seedman’ and exhibiting Gonzalez’s apparent obsession with bodily fluids to the full – ‘Spermadelic’, ‘Semen’, ‘White Blood’.

This month, 69 have their second album out, Adulte, a decidedly darker take on the post-punk sound of their debut Novo Rock. The group are quite comfortable with their borrowings being recognised.

According to Gonzalez "our music draws almost exclusively on post punk and New Wave, we use the instruments and the machines that belong and which were built in that era. A swing guitarist would be making a serious mistake if he played with a Fender Telecaster, so it is for us." I even spot a couple of lifts from Joy Division lyrics on ‘Black Dare’, and Gonzalez responds that "we started making music because of groups like Joy Division, PIL, Talking Heads, The Cure, Suicide and Devo, it’s such a rich period artistically that we never tire of it." Which makes 69 seems like a somewhat academic exercise, but I wonder what the title means for an album that seems divested of its predecessor’s more playful tone, all pingy ring-modulated sounds, sproingy guitar solos and a chorus of kids. Is Adulte about growing older and growing sad?

"Sadness is a feeling that’s very hard to express in music because you can’t fake. But we prefer to talk about frustration rather than sadness in the context of this album. Frustration can make you sad but it can also make you angry or plunge you into a state of silence; that’s common to everyone. We accumulate frustrations all through our lives and sometimes it’s necessary and essential to confront them and try to understand them. This record allowed us to open a door in our lives (Gonzalez and Peitavi are a couple). Emotionally it’s true to life, with a story within it that is autobiographical."

So post-punk seems to be Gonzalez and Peitavi’s means of accounting for themselves emotionally in the world, and perhaps to each other. That might explain why Adulte doesn’t feel entirely suffocated by its influences. It feels "true to life" as Gonzalez says, not just to form. I respond particularly to the slower tracks like ‘Black Dare’ and ‘March of the Enemies’ which, divested of vocals, could almost be Ekoplekz productions.

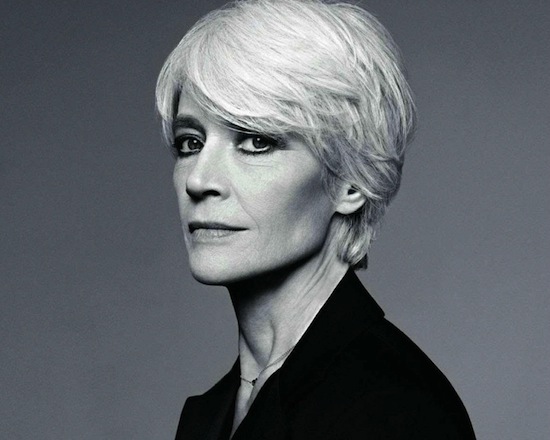

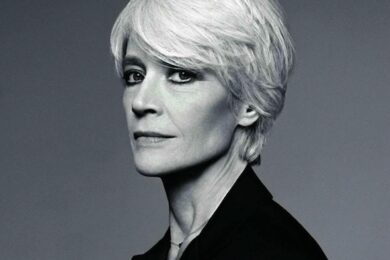

Also recommended is Françoise Hardy’s L’Amour Fou. Hardy will be 70 next year. At the age of 23, she released a song called ‘Ma Jeunesse Fout l’Camp’ (which translated roughly as ‘my youth is disappearing’) – I think she even has Morrissey trumped in the ‘old and world-weary before their time’ stakes. Some have accused her of never maturing as a writer or vocalist, but great later-period tracks like ‘La Verité des Choses’ put paid to that notion. Her voice has become deeper while its reedy quality has become more pronounced, and the songs resonate with the truth of more hard-won insights; it’s as though she’s caught up with herself. Perhaps it’s true that she doesn’t range too wide stylistically anymore – L’Amour Fou, apparently the ‘soundtrack’ to a book of the same name, is largely composed of the stately and ethereal ballads that are her stock in trade. But my crush is eternal; just the way she sings "alors, cours mon coeur imbécile" ("so run, my foolish heart") on ‘Normandia’ sends my own heart into a foolish swan-dive.

Anyway, even if it’s true that Françoise Hardy’s music is more or less unchanging, that’s fine because her only subject is love. "The old story again" you think, and the next moment you’re suckered.

For more from Rockfort, you can visit the official site here and follow them on Twitter. To get in touch, email info@rockfort.info.