While temperatures are escalating, things are equally hotting up in the jazz world. As signposted in last month’s column, legendary, anarchic orchestra Loose Tubes have re-assembled and put on some cracking performances around the country, not least at Ronnie Scott’s last month, as reviewed below. Elsewhere, tQ favourites Phronesis are currently in the middle of their own European tour supporting April’s mind-blowing Life To Everything, and I caught up with the trio’s charming and restless bandleader, Jasper Høiby, via Skype to discuss various matters – read the interview below. So without further ado, crack a cold one and get up to some of the freshest sounds in jazz…

Loose Tubes

Ronnie Scott’s, Soho, May 9, 2014

Laying dormant for 24 years with their first three CDs virtually extinct and few digital traces of their anarchic 80s heyday deposited on the web, 21-piece big band behemoth Loose Tubes seemed set to be confined to an obscure, distant strata of jazz history – up until now that is. Indeed, if you number yourself among jazz’s more youthful advocates (born in the 80s or 90s, perhaps), you could be forgiven for thinking aloud, "Loose who?" when the ragtag troupe, who blossomed out of a nutty student workshop and improbably marched their way onto Terry Wogan’s TV chat show, announced a comeback earlier this year. Yet on the other hand, if you’re of a certain (more experienced, shall we say) age, the herald of the return of this genre-defying orchestra must have been quite an enticing blast from the past.

Even if you hadn’t heard of Loose Tubes before now, why, you were probably already aware of the pioneering work of a small proportion of its alumni. Saxophonist Mark Lockheart, for instance, is one half of a double-barrelled sax-attack in British Mercury-nominated jazz-punks, Polar Bear. De-facto bandleader Django Bates is one of the most forward thinking and influential British musicians in any genre, a professor at two European universities, mentor to Norwegian saxist upstart Marius Neset and a one-time BBC Proms curator. The band also cultivated the talents of such headline-grabbing names as Iain Ballamy, Chris Batchelor and Julian Argüelles.

Coming out of retirement is par for the course for many an ageing rock and pop band who, if you take heed in some cynics, are looking to rejuvenate their waning bank balances. But for Loose Tubes, this reactivation was never about grasping at past glories or drumming up extra dough, with the band pointing out at the outset that they "didn’t want to be their own tribute act". Besides, acid-tongued MC and trombonist Ashley Slater made it perfectly clear what he thought about the monied contingent in the audience: "You’re rich, but you’ll never be in Loose Tubes," he intoned snarkily. "Think about that when you go home!" As it happens, it was a commission from BBC Radio 3 to produce new compositions that cajoled the crew, some of whom had to return from such far-flung destinations as Denmark and Brazil, to reconvene.

All 21 players took to the stage (some spilling off to the side) with surprisingly little fanfare. They got underway restrainedly with the cool but insistent currents of Bates’ ‘Yellow Hill’, but hit stride during the glorious wildfire of ‘Sad Afrika’, which smouldered and crackled with contrasting sheets of blazing brass. It was soon evident that in their 24 years apart, the band hadn’t lost any of their flair for pinpoint timing, intricate but hooky compositional smarts, grin-inducing energy and free-spirited inventiveness, all of which were crammed into their latest compositions. Flautist Eddie Parker’s ‘Bright Smoke, Cold Fire’ seemed to be a mind-link between John McLaughlin and Frank Zappa circa Hot Rats, decorated with a shimmering salsa backdrop. Elsewhere, trumpeter Chris Batchelor’s aptly titled ‘Creeper’ featured an ominous pedal note stamped throughout melancholic, waltzing folk themes.

Back in the 80s, the band were known to march the audience around Soho during their encore; they didn’t this time round, but half the band swaggered and snaked around the packed house instead, prompting all audience participants to get on their feet and jump for joy.

Bitch ‘N’ Monk – Fulafalonga

(Cadiz)

The seeds of this experimental male-female duo were planted in Taunton, which is somehow fitting, for Bitch ("beatboxing soprano" and guitarist Heidi Heidelberg) ‘n’ Monk’s (rock flautist Mauricio Valasierra) poison apple sound of jazz, folk and classical is in bitter proximity to West Country trip-hop miserablists Portishead, especially on the ragged, haunting ‘The Eagle’. Like Portishead’s Beth Gibbons, Heidelberg dishes out dark-hued affairs of the heart with stinging, deadpan poise, like on single ‘Did He?’, but in this case leavens the heartbreak with a west African-charged middle eight that vibrates with the sort of wacky, joie de vivre tUnE-yArDs is prone to – and that ain’t a bad thing. One bite of this mini album will send you into a lovesick coma and give you an electrifying kiss of life all at once.

Alexander Hawkins Ensemble – Step Wide, Step Deep

(Babel)

On Step Wide, Step Deep, British firebrand Alexander Hawkins and co. do just that. That is to say, they ramble freely across the length and breadth of free jazz history, unearthing emotions and melodies that’ll strike awe in the hearts of anyone dauntless enough to sit through this staggering album from beginning to end. This is the free stuff at its most bracing and surprising, not to mention its most accessible, similar in scope to the likes of Tim Berne’s Science Friction. But unlike Berne’s sinuous, gritty freak outs, Hawkins’ excursions to the brink of traditional form are pastoral and cinematic, taking in Bill Frisell-esque Americana and Can-like riff-repetitions along the way. This album features a host of British talents (drummer Tom Skinner/reeds extraordinaire Shabaka Hutchings) like you’ve never heard them before.

Neil Cowley Trio – Touch And Flee

(Naim Jazz Records)

Understatement is not a word you might typically associate with off-the-wall British pianist Neil Cowley. One-time keys man for acid jazz party-starters Brand New Heavies and hired hand for gushing pop singer Adele, Cowley’s last four trio project albums were hardly lessons in restraint, bounding as they did with punchy riffs, strong-arming rock rhythms and anthemic choruses. That said, 2012’s The Face Of Mount Molehill certainly tapped into a more classically-influenced, introspective state of mind, but on Touch And Flee the pianist pretty much goes the whole contemplative, Michael Nyman-echoing hog. While Cowley’s always been a sophisticated composer, despite his maverick streak, this album might well be construed as a coming of age record, with the wackiness of old being substituted for refined sangfroid. As such, some of the Cowley old guard might scratch their heads in puzzlement, waiting for the gut-busting hooks. The likes of ‘Kneel Down’ and ‘Sparkling’ could be filed next to some of E.S.T.’s more radio-friendly tracks, but there’s enough groove jiggery-pokery and brisk energy of old (‘Gang Of One’, ‘Couch Slouch’) to keep the album from tipping into coffee-table territory.

Matthew Halsall & The Gondwana Orchestra – When The World Was One

(Gondwana Records)

Trumpeter Matthew Halsall is the chief of trendy Mancunian label Gondwana, home of fiery power trio GoGo Penguin. While his young signees have a bent for racing off into the future, Halsall prefers to look back fondly into the past, his ambient, Gilles Peterson-approved jazz largely being imbued with the modal spirit of ’59. When The World Was One barely deviates from Halsall’s tried and tested route map, with its easy-going knack for a Dave Brubeck-like swing groove and John and Alice Coltrane-echoing spirit elevation, as on opening title track.

—

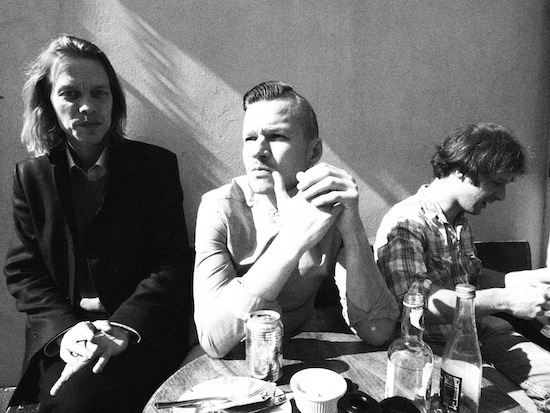

Cast your minds back two months. Scandi-Brit trio Phronesis (pictured above) released their powerful live album Life To Everything, a whirlwind of maniacal rhythms and switchblade riffs (composed in a mere four days, and recorded at the London Jazz Festival 2013) which cemented the band’s status as one of the most exciting and potent forces on the scene. In the midst of touring said album, bassist and de facto bandleader Jasper Høiby spared some time for me over Skype. In between several mugs of coffee (his band’s sound is similarly caffeine-fuelled), he discussed fashion, band democracy, playing with conviction and not wanting to play a supporting role for a "screaming saxophonist" like Marius Neset…

Phronesis means learning through practical experience, so what have you learned personally and musically in the nine years you’ve been on the job?

Jasper Høiby: Oh God. That’s a huge question. That’s the first question? Fucking hell… I’m learning a lot over time. Just the fact that we’ve played together for that long and stuck around with each other for that long, you can’t help but learn stuff, you know. Just developing friendships and working relationships like that for that long guides you into a lot of different alleys, so if you didn’t learn anything you wouldn’t last that long.

Nine years is a long time for any band. What’s kept you going?

JH: It’s still fun. I still feel like there’s magic going on between us when we play. It would be absolutely silly to put that to rest. A lot of people do a lot of sporadic projects, one project, one album, another project and another album, but I really think there’s something to be said for keeping a band together and developing it. This started out as my band but turned into, you know… it’s a band now, there are three reins for the horse.

Judging by your band’s name and your recent album, you’re obviously interested in the great Greek thinkers. Does their intensely analytical way of approaching things influence how you play your bass or compose?

JH: I studied a little bit when I went to the [Royal] Academy. I did one year – it was only a one-year introductory course – at King’s College, London. And that was an amazing experience. I’ve always been interested in that sort of thing but I didn’t really get my hands on it ’til then. It’s so different from any other subject, I think, and yet it’s totally relevant to all other subjects.

But have their ways of thinking directly influenced your playing?

JH: No, I don’t think so. Not in a direct way. It’d be too great a claim to think so. They affect your approach to life, maybe. But not playing.

Your band has a very strong, unique visual and musical aesthetic. Can you explain how and why your particular (natty and musically hyper) identity was forged, and was it your original idea in 2005 to have such a striking identity?

JH: All of that fashionable side was not conscious at all actually, I’m quite glad to say. Obviously there were moments where I was like, now we’re starting to get better gigs, we’ve got to shape up a bit – remember to not walk onstage with your trousers down, and wear the same colour socks. But Anton [Eger, drummer]’s always had that crazy way of dressing, and I’m not even trying to keep up with him. I just want to make sure I don’t look like I’ve just got out of bed.

So you don’t have make-up artists powdering your face up before you go on?

JH: Are you kidding me? Fucking hell. If I ever get to that stage please tell me to fucking stop… But I think we are very different people and personalities. Ivo [Neame, pianist] is from a totally different background from me and Anton and I’m from a different background to Anton. Ivo really didn’t care about he dresses. He’s come from a family that dresses well, so in a way he’s like, "Fuck that, I don’t care about that."

Yet he dresses pretty sharp too…

JH: He does now. But we had to talk about it. You can’t wear a fucking jazz festival T-shirt from five years ago onstage. So he’s shaped up. He’s finding it fun to be opposite someone like Anton who’s extreme with that stuff. Apart from that it’s still important to be comfortable, so I just wear what I’m comfortable in.

What about the music? When you initiated the band, did you have a clear vision of how the music was going to be expressed?

JH: A little bit. I already had a few other projects going on throughout art college. But this was a trio and I had written a fair amount of stuff before then and tried out other bands, so I had a good idea of what I liked. But what I’ve always liked is to have a setting where there’s no hierarchy, in terms of instrumentation and who leads and who doesn’t lead, that’s interesting to me. People say we’re a bass-led trio but that’s bollocks, but it’s not a piano-led trio either. I think it’s more of a case of leading together.

With the first three albums you wrote all the material, and now Anton and Ivo are bringing material to the table. What have they got you haven’t?

JH: Different perspectives. Ivo’s very good at writing mellow stuff, ballads, he’s really got a thing for beautiful ballads. So that’s something I’m working on, developing that side of my writing. But with him being such an amazing pianist that’s something he can just whack out. So that’s a huge plus. And Anton’s bringing his own stuff, he’s got another take on the rhythmic stuff we’ve been doing before. I guess he likes playing up to the visual side too. But he does bring that energy and he’s always done that, even when I saw him play before I played with him. So they both bring their own thing to it.

Do you get the final say on what goes into a track? And, if so, I’m interested to know what sort of ideas make the grade for you and what ideas get left out?

JH: That’s totally different from song to song. It was an agreement that now that we’re going to share writing duties, go three ways with this record [Wings To Everything], contributing and also financing the album, but I still have the last say, musically. It’s not really something that we talk about. But that’s where it started, with me giving directions and people involved in shaping where we were going, yet I could say, "Thanks, I’ll have that idea, or no, that doesn’t work". In theory that’s how it still works.

So how do you fit all the pieces together? Do you jam ideas or does someone bring in a score?

JH: We bring scores individually, sending it in advance if we can. We don’t rehearse much so that’s always the best way.

That’s so surprising that you don’t rehearse much, seeing as you seem to be one of the most telepathic bands on the planet…

JH: No, we don’t rehearse much because we don’t live in the same place. But we all just play a lot of gigs. There’s a lot of ropey gigs out there [laughs]. We play a lot – nine years, right? So that means that you don’t have to play that much, you know. We have 35, 40 tunes or something, so you need to keep some of it refreshed, but most of it’s there [taps head]. Before this tour – we had a bit of a break before this album – we played a huge showcase gig in Bremen and refreshed stuff before that on my own. We met up for a couple of hours in Copenhagen, but that’s unusual…

But I just wanted to say in relation to what you asked about what ends up on the editing floor, it’s really up to everyone again. Someone will bring a track along and we’ll play it with an open mind at first and then people will come up with suggestions or maybe the guy who wrote it will take it back and think about what could work. It’s a nice process like that. When we prepared all the material for the live album, we had four days of playing together without gigs, which was the first time we’ve ever done that. And then we had a gig at the Brecon Jazz festival last year. So we had four days together playing all this new material and shaping and arranging it and learning it. That was it. And then we played the gig at Brecon four days later with all this new material. And in that sense we tried it, workshopped it, decided this is what we’ve got to do. We turned up, played the gig and recorded it as well, so we had a reference for what the shape of these compositions were, and then we had touring after that.

So all the material for the new album was written rapidly, on the hoof, so to speak…

JH: Exactly. But that four-day session was the deadline for everyone to have their material ready.

And when you play it live, how much of what you play is improvised?

JH: It’s different for every song as well. But I think we mainly work with a formula, a framework, where you have different options within that framework. A song might be written out, an A-section, a B-section, maybe a tag and a C-section, or whatever. We’re very standard, old school jazz in that way. I like how old school jazzers play the melody, then the solos go round, a bit of improvisation off the melody and content. Harmony, melody and rhythm. We do the same. If someone breaks the rules and goes off, it’s not going to make any sense.

What things do you have to sacrifice in order to maintain your solid levels of democracy?

JH: Yes, I’ve had to sacrifice things to keep the band going. As a result, I’m only playing in two bands today. I used to play in ten! That’s why I’m not involved in a lot of things because this trio had to take the front seat. And the other guys have not done the same thing at all, they’re involved in more projects than I am, but there’s still stuff they have to turn down, because they have to prioritise.

It’s a very, very hard thing to plan gigs and stuff, I don’t think people think about it that much, but it’s really a nightmare trying to get the whole thing off the ground and get everyone to be in the same place at the same time. So in that sense we’re sacrificing things all the time. I have moments of thinking, "I could do anything with this trio and this trio could be an outlet for all my passions and ambitions." We’re all just trying to find our strengths, and find where that takes us and be open to that.

Can you elaborate on how you have contemplated assimilating all your ambitions and passions into the band…

JH: Music is very much about personalities and how people’s different tastes work out. So if I want to go and play really free with some people, well then Ivo and Anton aren’t really the people to do it with. I like to incorporate some of those elements into the music still, I’m not giving up doing that. But I’m always trying to be aware of what our strengths are, what our similarities are, what we have in common, what we can build on.

That’s interesting, because I also feel there’s a lot of things you could do with your band, a lot of different directions you could take it. Have you ever considered expanding beyond a trio or taking your sound in a different direction?

JH: We’re a trio. Whatever albums you do you’ve just got that line-up. But that’s the key of having a consistent sound I think. And that’s one of the reasons why we haven’t expanded, and as soon as you expand, you break that circle, break that magical number, three. And really it’s not the same any more. I’m not interested in this group to be the sideman and just go back into the bass role, stand in the corner and support some screaming saxophone player like Marius Neset for fucking twenty minutes, not in my band. That could be really good to do in another band.

We’ve thought about doing collaborations and other contexts but there needs to be some other element to it as well. We did a gig at the Queen Elizabeth Hall with Dave Maric who played electronics, and he wrote a tune for us, and Jim Hart played vibes on that as well. That was great, something else. It wasn’t us though; it wasn’t the same thing as the trio, but it was great and something that I’d like to explore. But still then that’d be a one-off thing. I don’t want to expand this band into another band, and in the end it’ll be like seven people, taking our sound to some new place. The sound is about the energy and the notes we play. For me I’m perfectly happy.

I love listening to piano trios. I remember discussing it with Ivo, and he’s tired of saying, "Yeah, piano trios, there are so many piano trios," and yeah, there are, but it sounds really good, that line-up. I love Bill Evans’ trio. I love Chick Corea’s trio, Roy Haynes’ trio album. There’s so many amazing suggestions of what this line-up can do. I don’t have a problem with it. I like playing with the piano more than I like playing with the guitar for example, because it’s not as loud [laughs]. Because of the volume, it’s not even a joke. It just blends really well and you can write compositions with piano and bass that just sound amazing. I’m just an acoustic music fan. But that being said, I don’t think it should stay traditional in any way. For me, piano trios sound modern, even though loads of other people do it.

Listening to your music, it’s clear there’s a lot of rock energy in there. Do you guys draw influences from rock and pop bands?

JH: There’s definitely an energy thing that I can relate to. But speaking for myself, I’m not a rock person. It doesn’t really get me going. Some things do, occasionally. But I’m not looking for it, not exploring it, no. Having Anton there is the total opposite. He is a rock kid. He likes that stuff. I’m sure he’s got as much rock music in his life as I do jazz. Ivo is similar to me, he likes some rock music, but it’s really not his thing. But we all share the idea that you have to play with conviction, you have to play with energy, you can’t expect anyone to listen to you if you don’t give them that. That doesn’t mean it needs to be aggressive. But recently on the last few albums we’ve been exploring quieter dynamics, as well as loud dynamics, I don’t know how much that comes across on our recording necessarily. It’s fun exploring the extreme, taking it as far down as possible, then as high up as possible. It’s all about the balance, and what’s in between. The whole ying and yang relationship.

I wanted to ask you about your Pitch Black gigs – will you ever be doing anything like that again?

JH: We plan to do it again, yeah. It’s fun and it’s significant. It’s cool, man, it’s something else. It’s another level, especially these days when everyone has their fucking smartphone, staring at it. We’ve done six of those gigs so far. But it’s really hard to put on, not every venue can do it. And also we like playing with the lights on [laughs].

What did you learn from playing in perfect darkness?

JH: It’s nice just to confirm that you can actually do that. Our connection is quite strong, so we can do it. I’m not saying we’re doing anything supernatural, people are like, "Woah, they play in the dark" but we just use our ears, that’s how it’s possible. There’s a few things, like piano, if you have to reach the strings. And also cue signs. You know, you hint going on to another section by playing something else, so that stuff is incorporated in the music anyway, but there are some bits when we look up for a cue, so we had to make a musical cue instead. Otherwise, it was all kind of natural

I remember the first one we did in Brecon, we played the second tune or something, and all of a sudden Anton left his drum chair and started drumming on the floor, walking away into the hall, he couldn’t see what he was doing anyway, and I was stood there thinking, "Oh shit, he’ll never find his way back, what is he doing?!" That was fun.

I have a sister who lost her sight. She’s a very inspiring person, even without losing her sight. She’s not had the easiest life. I moved back home because she lost her sight, so that’s the weird link that started this group. I dedicated the first album to her, the second album to her, it means a lot to me. In that way, I thought the Pitch Black gigs were important to do. And it’s just something no one talks about, blind people – does anyone really talk about them? I think it’s great to be able to give people a taste of what it might be like to be blind. Experience stuff without sight. I’m not Gandhi or anything, but [laughs]…

So what’s next?

JH: This when I get my diary out. As the summer rocks on we’ll play a bit in Belgium and the Netherlands, we’re playing North Sea Jazz Festival. So there are gigs throughout the summer, and there’s stuff for the autumn planned. Late August we’re going to Brazil for the first time, which will be amazing.

It’s interesting you’ve never played in Brazil, seeing as you’ve got a lot of Brazilian flavours in your rhythm section…

JH: Absolutely. Me and Ivo are heavily into Brazilian music. I’ve played with a lot of Brazilian musicians in London. It’s an amazing scene. Amazing music. You can’t sum it up. They have everything: melody, harmony and rhythm all going on at once, it’s incredible. I can’t wait to go.