PJ Harvey surprised many last year by bringing out an album so small in scale, so finnicky and chilly, that many critics saw it as a stubborn step back into dilemma by an artist who flourishes there. Though Harvey’s Stories From The City, Stories From The Sea and Uh Huh Her have seen the majority of her commercial success, stylistically White Chalk saw her taking more risks than at any time since her first solo record, 1995’s To Bring You My Love. Working principally on the piano, until then an unfamiliar instrument, Harvey’s compositions became a specialist lens through which to view spectral characters and stories otherwise lost to view. Both To Bring You My Love and White Chalk were produced by John Parish, his approach a dextrous combination of flexibility and sureness of touch perhaps needed by such otherwise static and abhuman records.

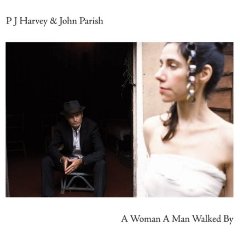

The release of A Woman A Man Walked By sees the pair’s second collaboration with Parish in the songwriter’s chair, the first being Dance Hall At Louse Point, the 1996 album into which Harvey retreated after the effort and exhaustion of To Bring You My Love. Louse Point found Harvey sending her narrators out to wander the sinister mazes of Parish’s songs, an approach she clearly found liberating; her subsequent album, Is This Desire, contained some of her most accomplished, confident character writing to date, finally seeing off the biographical readings that had dominated critical response to her work until then.

Once again in A Woman A Man Walked By Parish has provided the settings for Harvey’s lyrical and vocal explorations. Perhaps fittingly after such a long wait, here the overriding feeling is one of glee; there’s a familiarity in contending for space among Parish’s often laden tonal picture. Where the lyrics might seem bereft or even hopeless, the tone is often contrastingly bold, even knowing. Harvey plays syllabic guessing-games, chasing from phrase to phrase of Parish’s arrangement. "Pieces, pieces of my love," she sings almost triumphantly over a swelling, urgent piano and percussion break, before abruptly settling down into a set of descending phrases like a nesting duck. In the song’s final moments, to no accompaniment, Harvey tells its whole secret story: "..washed away in the water that took my son."

It’s a cold heart or a brave black humour that can abandon such a line in the reeds, and elsewhere on this album, a piratical swagger lends distance to Harvey’s almost Von Trierian penchant for feminine extremity. Whether daring her lover to outblacken her heart (‘Black Hearted Love’) or squealing and barking in animalistic protest (‘Pig Will Not’) , Harvey’s gutsy take on genderfuck is literal and particular, an organic critique. The title track is especially explicit: Harvey explores the "lily livered little parts", the "chicken liver balls" and "damp alleyways" of a cowardly "woman-man", joyfully enumerating his various lacks, his premature balding, his inadequate "little toy", before concluding "I WANT HIS FUCKING ASS". Parish’s skewed, simple little riff gradually yields to thunderous drums that counter the vocal rhythm. This is no mere murder ballad; this is torture stomp. Harvey’s sexual aggression and gendered take on body horror owes much to Diamanda Galas, whose blithe take on sexual revenge is possibly best captured in ‘The Sporting Life’, as she chatters and cackles her way through the rape, torture and lynching of a trick by prostitutes.

For all its cocksurety and buttlust, this album deftly isolates some moments of dreamy uncertainty. ‘Passionless, Pointless’ is a photographic re-examination of an ended relationship, casting slight variations of perspective on the same small, telling events: "I slept facing the wall; I dreamed of buildings in pieces. You slept facing the wall, and you wanted less than I wanted." No modern songwriter is more capable of enumerating heartbreak’s immersive power than Harvey; snapshots of memory are examined for clues and flicked to the floor. But the pictures change for the looking, become meaningless. "I don’t remember," sings Harvey quietly. "How did we ever…?" Parish’s guitar shimmers a chordal cloud of disquiet over the verses, then picks a silver thread through the refrain, and discordant flutes contest one another for a way through the confusion. Musically as much as through the narrative, the song argues persuasively for the phantasmagorical turmoil in everyday tragedy, the awful specialness of common loss. It’s Harvey’s good fortune that in this collaboration she can make such characteristic work, and Parish’s loss that his contribution may well be overlooked by fans, frustrated by the trenchant experimentalism of White Chalk, who are waiting for Harvey’s return to the blues-based rock idiom.