We knew roughly who Peter Gabriel was in 1986, of course. The wannabe drummer who’d co-founded Genesis, only to leave eight years later in 1975 and inflict Phil Collins upon the world as a frontman, had a reputation for eccentricity, dressing up during the prog-rock act’s shows as, for instance, Britannia or a giant flower. He’d also had solo hits – ‘Solsbury Hill’, ‘Games Without Frontiers’, ‘Shock The Monkey’ – though ‘Biko’, his now famous, bold response to South Africa’s Apartheid system, had, comparatively, flopped.

Nonetheless, the idea that the ex-public schoolboy would top album charts around the world, help change the face of music videos, and arguably dissuade countless people from committing suicide – an extraordinary claim for a musician – was unlikely to have crossed many minds when Gabriel stepped into the cowshed that had been converted into studios in his Avon countryside garden at the start of sessions for So.

Gabriel, too, probably never thought of So as a potential game changer on such a grand scale, but he’d set out in early 1985 to make a record that was more commercial and accessible than the work that preceded it. Much of his recent time had been spent composing and recording the dense soundtrack to Alan Parker’s award winning 1984 film, Birdy. As he recounts in the liner notes to this genuinely deluxe reissue of So, he "wanted to get back to a more traditional form of song writing, to have some fun, to be a bit less sombre and mysterious". Given Birdy‘s claustrophobic nature, it was hardly surprising that he felt the urge to loosen up. Since much of the score involved immersion in older work that he had chosen to revisit for the project, it’s understandable that he wanted to explore new territories.

What would emerge from the intense months ahead, however, was a huge leap even for someone looking to take giant steps. The following year he’d pick up two Brit Awards, receive four Grammy nominations and headline Earls Court four times as part of 1987’s 68 date This Way Up tour. It was a more than healthy reward for the ten months (at least) and £200,000 that Gabriel invested into So‘s creation, and one that reflected an artistic reinvention that remained largely uncompromising.

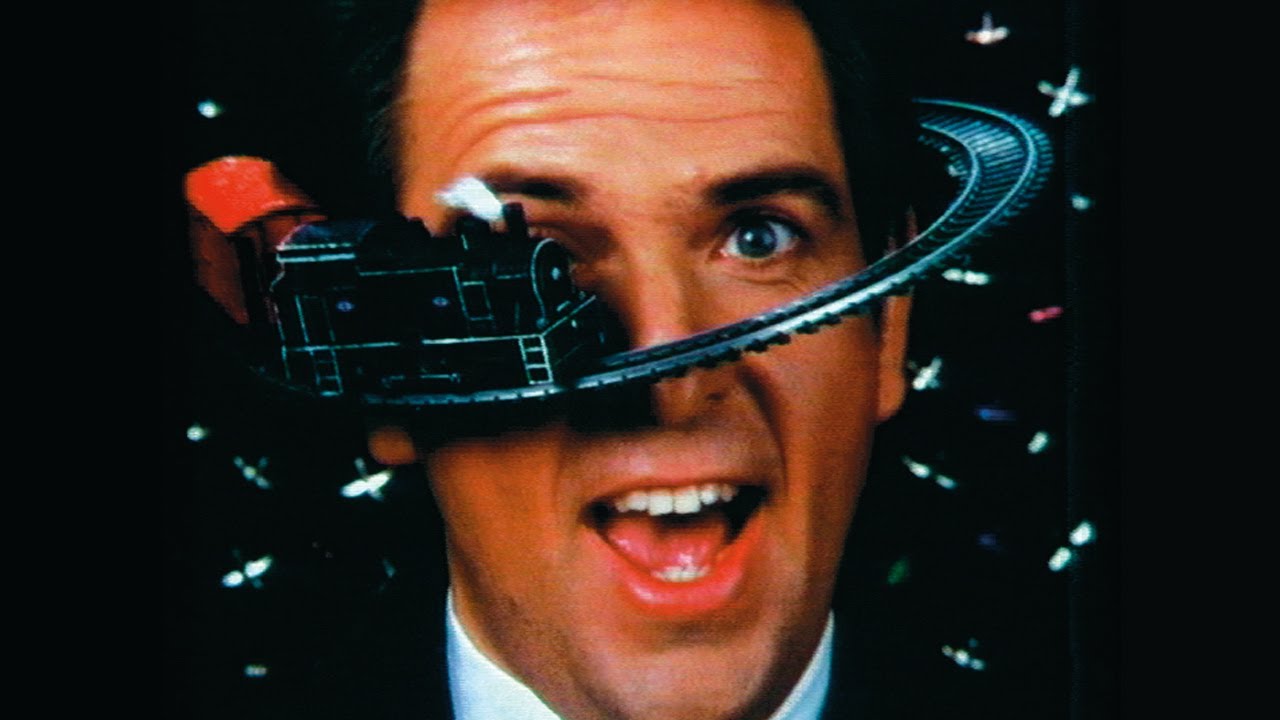

Was So really as good as its sales and plaudits suggest, though, or one of those fluke hits that catch and ride a wave? Certainly the video for lead single, ‘Sledgehammer’, did no harm: ubiquitous upon its release, it’s said to remain MTV’s most played video of all time, and its innovative content was indeed both thrilling and witty thanks to director Stephen R Johnson, stop motion animators the Quay Brothers and an at the time little known company called Aardman Animations. But to suggest that it did anything more than hurry So‘s success along on its path to success is to underestimate not only the song itself, but the album as a whole. So, you see, was not a ‘Will this do?’ collection. It was a meticulously crafted set, one in which almost every detail seemed carefully considered.

Daniel Lanois’ production helped, its immaculate warmth giving each note room to breathe, its textures lavish (in the preferred style of the time) without being sterile. Gabriel was already familiar with him after they’d worked together on Birdy, and the Canadian producer was ideal for what Gabriel had in mind, equally at home with bombastic constructions – he’d produced U2’s The Unforgettable Fire two years earlier – as with more ambient, introspective work, having lately masterminded sessions with Brian Eno, Harold Budd and Michael Brook. Gabriel’s choice of musicians was also significant: the album’s credits include Laurie Anderson, Bill Laswell, Simple Minds’ Jim Kerr, soul singer P.P. Arnold, David Rhodes (who had contributed to Talk Talk’s ‘Life What You Make It’ the previous year), French / Ivorian percussionist Manu Katché and Senegalese singer Yousso N’dour. It wasn’t an obvious selection, but it served Gabriel’s purposes perfectly, the combination of styles and backgrounds investing something fresh and unfamiliar into the results.

So begins dramatically with ‘Red Rain’, its mixture of programmed and live drums (with additional hi-hat from The Police’s Stewart Copeland) echoing the sound of a downpour in an ominous landscape of intense bass, piano and guitar. It finds Gabriel reconstructing what he calls in the liner notes "an apocalyptic dream", his throaty voice reaching anxiously for its higher registers. It’s a stirring opener, and that it’s immediately followed by ‘Sledgehammer’ adds to the sense that Gabriel has embarked upon a more easily digestible version of his art: the title is indicative of the song’s insistent beat and full-blooded brass arrangements, which feature, amongst others, trumpeter Wayne Jackson, whom Gabriel had seen perform with Otis Redding when he was 17.

The title also referred to the sexual act: somehow, amid the soul-influenced, triumphant mood, he managed to slip less than delicate lyrics like "You could have a steam train / If you’d just lay down your tracks" and "Open up your fruitcake / Where the fruit is as sweet as can be" past the same censors who’d banned Frankie Goes To Hollywood for the use of the normally innocuous word ‘come’ two years earlier. Perhaps the playful lyrics and upbeat tone, combined with the hugely diverting video, ensured that people were simply too busy singing along to wonder what the words actually meant. Either way, so instantly memorable was the song that it topped the charts in the US as well as reaching number four in the UK.

‘Sledgehammer”s success confirmed that Gabriel had the potential to reach a larger audience, and there were further songs on So to satisfy newcomers. ‘Big Time’, for instance, the album’s third and final single, was its musical kissing cousin, brash and colourful. Though he sweetened the pill with slick funk guitar and yet more frantic rhythms – as well as a particularly percussive bass sound, achieved by drummer Jerry Marotta hitting the strings of Tony Levin’s instrument while the bassist picked out notes on the neck – it also warned that Gabriel remained unafraid of addressing grand themes. A satirical look at the economic consumerist boom enjoyed by those who’d not been affected detrimentally by Thatcher’s policies, ‘Big Time”s intent was once more possibly lost on a wider audience who revelled in the idea of "so much stuff I will own". There must, however, have been a perverse pleasure in knowing that he had again smuggled protest into the mainstream, his distaste for contemporary greed articulated most memorably in the lines, "They’re amazed / When I show them round my house, to my bed / I had it made like a mountain range / With a snow-white pillow for my big fat head". (No doubt Gabriel also revelled in the irony of audiences chanting along with the hypnotic, robotically repeated title of ‘We Do What We’re Told (Miligram’s 37)’.)

‘That Voice Again’ was, if less immediate, similarly far from subdued, Gabriel exploring themes of judgement – his voice sustained for well over ten seconds on the final syllable of the crucial line, "Only love can make love" – while Katché’s rhythms tumbled forward irresistibly. Katché also contributed to ‘This Is The Picture (Excellent Birds)’, a song co-written over 48 hours in Laurie Anderson’s apartment for pioneering video artist Nam June Paik, and ‘In Your Eyes’, the album’s final track. The former is an enigmatic experiment in atmosphere that features Chic’s Nile Rodgers, while the latter brings with it an overwhelming sense of redemption and closure. It’s additionally distinguished by the sense of relief felt as the song slips into its chorus – "In your eyes / The light, the heat / In your eyes / I am complete" – and N’dour’s exuberant cameo a minute before the fade, his voice wailing in rapture, occasionally punctuated by doo-wop singer Ronnie Bright (of The Coasters).

Rhythmic patterns like Katché’s were central to much of So, but, in contrast to many of the artists exploring what was thought of as ‘world music’, Gabriel considered rhythm "the spine of the music" rather than an add-on.

Amusingly, he admits that his already burgeoning interest in African styles was extended and facilitated by Pan Am’s Airmiles programme, which allowed him to fly to Brazil for free. There he met up with Djalma Correa, who introduced Gabriel to the sound of the ‘forro’, the shuffling pulse – employed subtly rather than as a decorative medal – that provides the foundation for the haunting ‘Mercy Street’. Dedicated to poet Anne Sexton, the song took its title from a play she’d written about the search for a father figure, and its mood is reflective, its nocturnal ambience leaving Gabriel’s harmonies – recorded early in the day to ensure that they were lower than normal – space to gleam above the twinkling sounds of Correa’s triangle. The lyrics reflect the music’s character, Gabriel almost murmuring lines like, "All of the buildings, all of those cars / Were once just a dream in somebody’s head" and culminating on a positive note, Sexton’s search depicted as fulfilled with a cryptic but abiding resolution: "Anne, with her father is out in the boat / Riding the water / Riding the waves on the sea…"

Of course, So‘s most enduring and resonant song is ‘Don’t Give Up’, the album’s unlikely second single, a six minute plus collaboration between Gabriel and Kate Bush. Covered countless times by a wide range of artists, from The Shadows and Sarah Brightman to Willie Nelson and Bono – though, more than 25 years after the original’s release, none of these have succeeded in diminishing the original – it was also chosen collectively in 2009 by Take That as one of their greatest inspirations. But don’t count that against a song whose ability to touch people from all walks of life is proven. It was partially fuelled by fury at Thatcher’s failure to control rising unemployment, but, he confides intriguingly, thanks to its twin source of inspiration – Dorothea Lange’s ‘Migrant Mother’, a photograph of a woman and child taken fifty years earlier during the American depression – he’d originally considered Dolly Parton as his vocal foil. Fortunately, Parton rejected Gabriel’s invitation, and, Gabriel confides, "I’m glad she did": his subsequent choice allowed Bush to turn in arguably one of the greatest performances of her life.

In all honesty, the fact that the song is about economic suffering is largely lost, transparent references restricted to the words, "For every job, so many men / so many men no-one needs". Beyond that, it’s a heart-rending depiction of "a man whose dreams have all deserted" forced to contemplate the ultimate response to the futility of his life. Absorbing, full of resigned tenderness, Gabriel nonetheless behaves like a detached observer: "Got to walk out of here / I can’t take anymore," he sings in one of the album’s most poignant moments, "Going to stand on that bridge / Keep my eyes down below / Whatever may come / And whatever may go / That river’s flowing". It’s this sense of disengagement that gives his performance its strength: he’s like a man aware of the situation in which he finds himself, but too spent even for self-pity.

It’s hard to believe – but nonetheless true – that Gabriel didn’t initially conceive ‘Don’t Give Up’ as a duet. Sung by one person alone, the encouraging tone of what later became Bush’s lines might have come across as little more than empty, hopeless and self-delusional. Instead she soothes, her simple instructions – "Don’t give up, ‘cos you have friends / Don’t give up, you’re not beaten yet / Don’t give up, I know you can make it good" – delivered in a composed, almost lugubrious fashion, caressed as they leave her mouth. Her role is that of comforter, of guardian angel, her disembodied voice providing the kind of calming reassurance that no doubt everybody wishes they could sometimes find, and by the time she reaches the bridge – "Rest your head / You worry too much" – it’s impossible to imagine anyone else sounding so affecting.

But it’s the final lines that have most effectively alleviated the grief and despair of so many people since, the litany of reasons to remain strong in the face of adversity intimate, sensitive and penetrating: "You’re not the only one", "No reason to be ashamed", "You still have us / We’re proud of who you are". Bush’s voice then soars one last, conclusive time – "’cause I believe there’s a place / There’s a place where we belong" – lifting her audience out of the slough of despond Gabriel’s persona has inhabited, before a closing instrumental coda provides the final payoff: hi-hats twitching over a serene, dubby sixty seconds that fade out, suggesting, in their lack of finality, that the old adage is true. Life goes on.

Just how much Gabriel agonised over the record is evident from the So DNA CD included in the deluxe set. On this, he splices together versions of album tracks using edited sections of original sketches and demos – "For many, many years, I have had a rule that if music is being made it must be recorded," he reveals – allowing listeners to investigate his creative process in a fashion so transparent as to be almost pornographic. "The picture," he admits, "is not always flattering," but – although there are moments when he does indeed sound a little rough – this is a brave and genuinely fascinating way of offering insight into the way these songs came to be. In fact, for those who have lived with So for over quarter of a century, it’s hard not to be genuinely thrilled by the experience of learning what might have been by discovering these parallel universes.

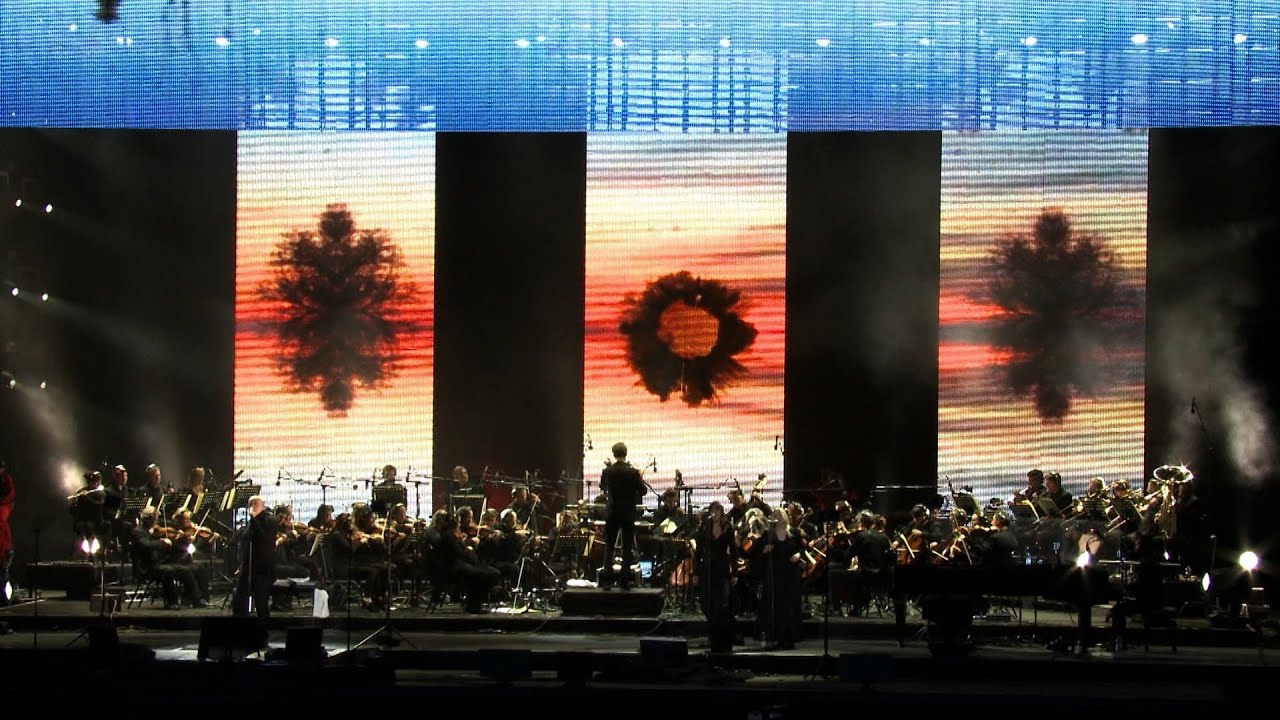

There is other material available included on these reissues: the deluxe edition offers a previously unreleased, two CD and single DVD set recorded during the final Athens dates of his 1987 tour, as well as a documentary about the making of the album and three previously unheard recordings, while a three CD version focuses on the original album and live recordings. In the long term, these components may prove more valuable for fans, with the live material providing a tidy resumé of his solo career up to that date. But So DNA is genuinely enlightening: rather than exploits fans’ gullibility for profit, it offers a chance to hear the artist at work, months condensed into an absorbing hour-long journey. It finds Gabriel feeling his way, agonising over songs, reshaping them, circling around the melodies like a pilot looking for a perfect landing, playing with lyrics and intonation as though exploring a new language.

‘Sledgehammer’, for instance, is almost unrecognisable in its earliest form, Gabriel wailing over a simple beatbox rhythm, the track’s instantly familiar introductory fanfare tentatively teased from a piano. The song’s embryonic tune is, in contrast to the final version, sluggish and full of grunts, but So DNA‘s six and half minute mega-demo-mix, if you will, records its slow transformation into the massive, exuberant, soul-influenced hit that it became. All but two of the album’s songs are pieced together similarly, but even those where he lacked comparable material – ‘This Is The Picture’ and ‘We Do What We Told (Miligram’s 37)’, where he was unable to track down as much tape – are presented in a manner which remains illuminating, the latter song’s early embodiment instead replayed from memory. This fast forward through Gabriel’s modus operandi is about as close as one can get to stepping back in time and observing him directly in the studio, and only enriches the experience of returning to the final version to evaluate it some 26 years later.

If one were forced to choose a single quality that makes So such a remarkable album, it would most likely be its sincerity. It’s not necessarily the attribute that earned the album a place in Robert Dimery’s 1001 Albums You Must Hear Before You Die, where the greatest compliment is reserved for the fact that "no other mainstream star has done so much to introduce artists to music they may otherwise not hear". It’s not the ingredient that won much of the critical praise given to the record at the time, which instead focused on the integration of Gabriel’s growing interest in the aforementioned ‘world music’ into its fabric. In addition, the success of ‘Sledgehammer’ and its follow-up, ‘Big Time’, may have distracted from the empathetic vulnerability evident elsewhere on the record, while Lanois’ glossily digital production pins So‘s release firmly to the mid 1980s like a butterfly to a cork board, ensuring that it has never been one of those timeless records that receives regular acclaim from each new generation.

But, without the occasional husky, early morning gruffness to Gabriel’s vocals, without the restrained but sophisticated musicianship, without the lyrical gems that wrench the heart – "I come to you defences down / With the trust of a child" (‘Red Rain’); "In your eyes I see the doorway to a thousand churches / In your eyes, the resolution of all the fruitless searches" (‘In Your Eyes); "Drove the night toward my home, the place that I was born, on the lakeside / As daylight broke, I saw the earth, the trees had burned down to the ground" (‘Don’t Give Up’) – So would merely have ended up a clinical exercise in adult orientated pop. Instead, it’s a heartfelt journey through intense emotional territory, assembled and arranged with intricacy and commitment, laboured over with such care that it sounds effortless. It may not be his most challenging work, but it proved that one’s vision need not be impaired when one steps deliberately, purposefully, into the limelight. Like the simple cover portrait that adorned its sleeve, So showed us who Peter Gabriel was.

So? So, so good.