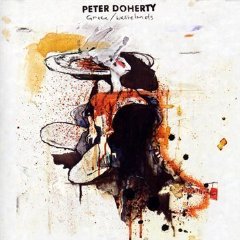

In a parallel universe, someone has taken Pete Doherty’s cultural obsessions and musical touchpoints and made beguiling music that explores Englishness in a subtle, intelligent and sensitive fashion. For the mine in which Doherty has laboured since the early days of the Libertines is a potentially rich one indeed – Grace / Wastelands finds him quoting Quentin Crisp and Wilde, and evoking 40s swing and louche, smoky nightspots, Tony Hancock and the classic sitcom, and the togs of yesteryear. The trouble is, Doherty has yet again failed to hit the richest seam.

Still, at least he hasn’t added to the monstrous slagheap that is the rest of his work post-Libertines. Instead, Grace/Wastelands is a curiously flat album. The melody and the shuffling beat that open recent single ‘Last Of The English Roses’ at first make you think, bizarrely enough, of Gorillaz’ ‘Clint Eastwood’. The feeling doesn’t last. ‘Salome’, far from being Wildean, comes across like an acoustic Arctic Monkeys b-side. Doherty’s vocals still sound contrived, a thick and furry tongue making unnecessarily grandiose flickers around a stained and bleeding mouth, though admittedly it’s blessed with a little more clarity than of late.

‘New Love Grows On Trees’ is actually a Libertines track that’s as much as a decade old. In it, Doherty sings to Carl Barat, "If you’re still alive / when you’re twenty-five / shall I kill you like you asked me to?" It’s a line that sums up Doherty’s fatal flaw as songwriter and artist. His is still a deeply romantic, slightly teenage idea of destiny and fate, of friendship and love; his concept of Englishness naive. For a few moments of The Libertines, this undeniably gave the man some charisma. But after everything that’s happened since? This failure is best represented on ‘1939 Recurring’, an ode to his grandmother "going west", once as an evacuee in World War Two, and more recently to an old people’s home. There’s surely potential here for an affecting track that explores both our relationship with the past and a side of Doherty far removed from what we’ve come to know – but it’s an opportunity missed.

Part of the problem is in the finish. Whereas the Babyshambles material sounded like the desk was operated by a bunch of people more keen on refreshment than refinement, Grace / Wastelands is bizarrely overproduced. The acoustic guitar is cold and anaemic, the string arrangements tacked on and sickly. This is presumably entirely opposite to what Doherty was intending on what could have been, at times, a thoughtful, reflective, deeply personal album. In the more rinky-dinky moments, what inspired The Libertines’ most pernicious legacy is unfortunately still all too obvious – wasted newsprint might rot, but The View are still very much with us.

There’s a brief flicker of life towards the end of the album in ‘Broken Love Song’, which is blessed with a terrific chorus that – for perhaps the only time – feels heartfelt. But then you realise it’s about living in a caravan under the Westway after your sniffy-nosed supermodel missus has chucked you out, and sympathy and interest fade.

Doherty’s own ego, intelligence and sense of self, warped by drug abuse, seem to have left him immature and half-formed, with little grasp of his place in the world. Bump into him stumbling around East London, and you’ll see a man convinced he’s a flâneur tramping Arcadia, rather than wandering past fashion students on the the piss-soaked streets of a once great city enslaved by chain shops and commerce.

Ultimately, Grace / Wastelands doesn’t even deserve to be a recipient of critical opprobrium. It’s nowhere near as bad as the two Babyshambles albums; but then again, very few things are. It’s merely a slightly middle-of-the-road record that never quite manages to define what it wants to be. Therein lies its biggest surprise. What happens next for the Major’s son is anyone’s guess, but on this evidence he won’t be going out with the bang anticipated by the coffin-chasing tabloids… but instead, shuffling into obscurity with something of a whimper.