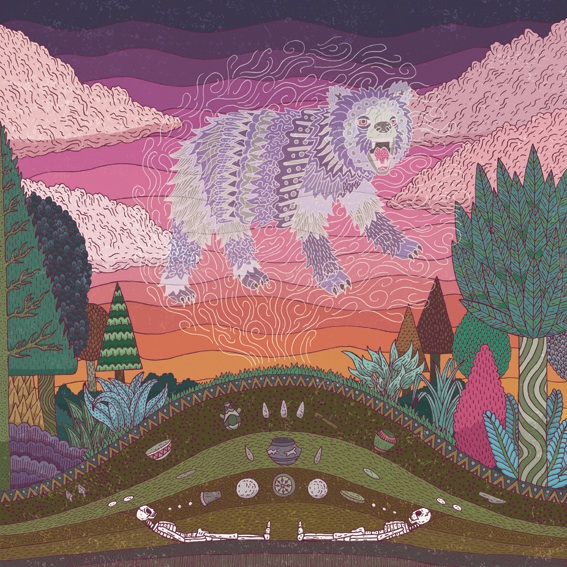

The spirit of the late, great Pelt guitarist Jack Rose hangs noticeably over Effigy. "I carry Jack with me", band member Mikel Dimmick stated in a recent interview, and track titles like of ‘Of Jack’s Darbari’ and ‘Ashes Of A Photograph’ seem to clearly reference Rose and his tragic passing at the age of 38. Musically, as well, Effigy is one of the most sombre albums in the entire Pelt canon. Where their previous high-water mark, Ayahuasca, balanced its noisier elements with beatific, relaxing moments of warmth and calm, Effigy is a brooding and intense listen, as if the quartet is trying to exorcise the ghosts of the past. Even the album’s title, which references the famous Native American wildlife-shaped mounds of Dimmick’s home state of Wisconsin, suggests the possibility of conjuring up departed spirits from the interstices in the band’s interplay, or via the cosmic union of their instruments.

‘Of Jack’s Darbari’ opens Effigy in a scattered cloud of dissonant violin scrapes and arhythmical guitar strumming before gradually settling into a suspended drone-filled raga. Displaying a focus reminiscent of Tony Conrad’s Four Violins, founder members Mike Gangloff and Patrick Best, accompanied by new(er) members Dimmick and Nathan Bowles, release and re-seize their clustered notes, twisting them into circular loops that fray at the edges, as if the whole thing could collapse into noise at any moment. A piano slowly emerges from the tumult, but its repeated sound clusters are reminiscent of Charlemagne Palestine, becoming a symbiotic part of the overall drone vista.

Having jettisoned conventional structure years ago in favour of this monomaniacal form of maximalist just intonation, Pelt appear to be reaching new heights on Effigy, with each track a demonstration of the members’ ability to listen to each other as they layer up their varied sounds. Even on ‘Wings of Dirt’, which starts with loping Appalachian banjo arpeggios, chirpy percussion and warm fiddle tones, soon peels these elements back onto themselves, with the strings see-sawing back and forth over the rhythm in a manner strongly redolent of Henry Flynt’s "hillbilly" take on minimalism. ‘Spikes & Ties’ is built around chiming singing bowls and humming harmonium, its languid pace and mellow warmth a pensive reverse image of ‘Wings of Dirt”s buzzing energy and reiterating Pelt’s musical ties to Eastern musics such as Pran Nath’s ragas or Indonesian Gamelan.

What is so singular about Pelt, and Effigy by inference, is that, for all these disparate musical strands that they seem to be tugging at (Appalachian country-folk, loft-suited minimal drone, Eastern spiritual music), they always sound fundamentally like themselves. The curiously-titled ‘Last Toast Before Capsizing’ features 11 minutes of percussive storm, with crashing cymbals, jiggling bells and bashed piano competing for space. In theory, its sprinklings of free improv and jazz textures should sound anachronistic alongside the dronier, more "rustic" works that surround it, but as it winds to a close, it somehow becomes imbued with the same becalmed spirit that ran through ‘Spikes & Ties’. Tension released into quietude: maybe that’s the secret behind Pelt’s uniqueness. How they manage it whilst casting their ears in such disparate, but cohesive, directions is perhaps a mystery worth maintaining.

It all comes together beautifully on the 22-minute ‘Ashes of a Photograph’ which, considering the aforementioned references, starts almost jauntily with a plucky Jew’s harp contrasting with the scythe-like violin to almost comical effect. Best’s voice emerges out of the haze of increasingly dense strings, a wordless, emotionally-resonant chant that seems to call and respond to his companions’ drones, like Marian Zazeela dueting with Tony Conrad and John Cale’s violins on Day of Niagara, but with the context surrounding Pelt transforming his moans and chants into a baleful lament. Like those masters, the regularity (for want of a better word) of the musicians justly-applied notes and tones renders time elastic, distorting perception until the music becomes the focus of the body’s impulses. For all their hillbilly sensitivities and rejection of the academic loftiness of a lot of minimalism, Pelt are still today’s most visible descendents from that tradition. In fact, it’s because they do not preoccupy themselves with high-minded concepts, and never detach themselves from their past, their souls and each other, that Pelt are able to create music that is as deeply thoughtful as their famed forbears, but also so immediately resonant with(in) the listener.

Effigy is a word that can mean many things, both within the context of Pelt’s history, and to outside considerations of American history or global mythology. As an album, it crosses many boundaries whilst drawing them all together, and crystallises why these four guys remain one of the most important, affecting and interesting bands around.