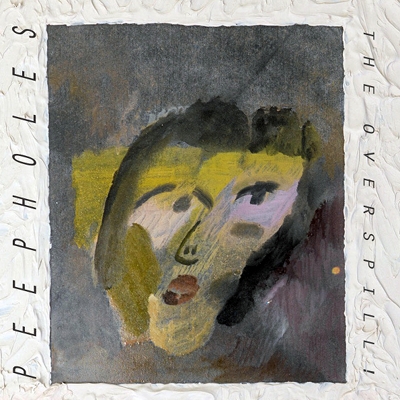

The Overspill! begins with the menacing ‘Ah Ah Ah’, singer/drummer Katia Barrett’s voice coming out of the dark like a mournful call in the night. The driving, repetitive synth played by Nick Carlisle is surprisingly punctuated by eerie pipes (of the pan variety), and combines with echo chamber vocals to set the scene for a strange and beautiful album, described as Peephole’s “debut album proper” by their London-based underground label Upset the Rhythm.

Less ear-shredding than their previous release Caligula, The Overspill! has dark digital warmth to it that never allows the listener to get too comfortable. The throbbing undertones and centre-stage synth feel half-familiar, the title track in particular evoking the 80s. The gentle weariness, like a last dance at the end of a long night in shadowy, electronic gloom. This is not a criticism, for it’s one of my favourites from the album, and the cleverness of Peepholes is that they tantalise you with this familiarity only to abruptly veer off into unchartered territory.

This makes the album a strange listen the first time round. To describe Peepholes as “punk”, as others have, is to describe the world they reside in rather than the music they make. They are punk in the sense of their experimentalism, their commitment to DIY labels and the spaces they perform in (this album was recorded after two days of experimentation and improvisation at Power Lunches, a tiny but invaluable home to many a lo-fi, “this band will save your life” show). But honestly? This album veers towards prog at times, so anyone looking for a quick fix will not find it here – ‘Living in Qatar’, the final track on the album is 14.45 min long.

The Overspill!‘s often freeform sound evokes landscapes, sea caves and deserts, forest-covered mountains. Expansive and cavernous, it becomes hypnotic if you let it in. The darkness it exudes is less goth, and more the black eternity of space, though at times Katia’s vocals recall the horizon-scraping reach of Siouxsie. ‘Pinnacles’ serves as an example of this, as her voice provides the goose-bump inducing element to the undulating rhythm. The experimentation with steel drums on songs such as ‘We Don’t Like Anyone’, as well as the aforementioned pipes, serve to lift the album out of being merely a homage to the digital instrument, and seems to allude to the multiple influences and origins of Barrett & Carlisle.

Fittingly, the album comes across as an overspill of ideas that have been captured and shaped to a degree, but are largely left open to interpretation, touching nodes of nostalgia and then rejecting them. There is a joy to this melancholic noise.