1971 was a god awful time for music. Acoustic guitars weren’t so much machines to kill nazis as instruments utilised by entrepreneurs hiding behind beards. The pervasive sound of sunshine folk was a prefab sunshine used to power a malignant, corporate agenda, duplicitously simulating a naive hippy dream the protagonists knew had died a death at the end of the 60s.

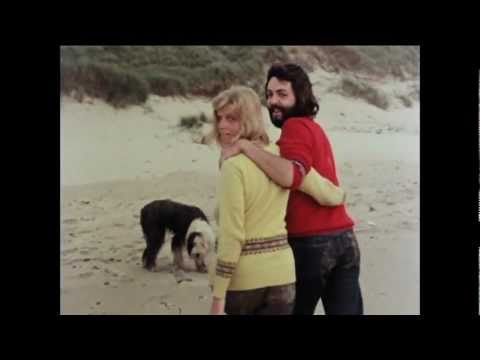

By this time however, Paul McCartney was so ensconced in conjugal felicity and isolated from what was going on beyond the homey domesticity and tranquility of his farm that the outside world must have seemed like a distant noise. In the 1960s he’d influenced everything in a way he never could have imagined, but having killed the Beatles monster he was free to indulge himself. Having proved everything he needed to prove, his music no longer fed his ambition, and the next decade would see him driven by whimsy and curiosity. As one half of the most successful songwriting partnership the world had ever known, who could argue? He might have lost his chief quality control officer in John Lennon, but Ram is a record that clearly doesn’t concerned itself with public approval.

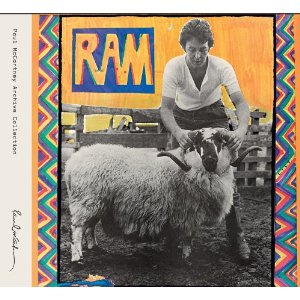

According to the singer, it was never really meant to see the light of day. McCartney had taken to bed with his wife and not bothered alerting the world’s press like his old partner in crime. Having asked Linda to join his “band”, Ram stands as the only album in his considerable discography credited to Paul and Linda McCartney. The naysayers will complain that Ram is unfocused and sometimes unfathomable, but that’s one of the things to love about it. The sheer ebullience, the devil-may-care attitude taken in the construction of these songs, makes it an album to treasure.

Take ‘Monkberry Moon Delight’ for instance, with its stream-of-consciousness lyrical nonsense (“sat in the attic / piano up my nose” or “when I leave my pajamas to Billy Bupdapest”); it grooves along like some early Tom Waits’ jam, with a hook that by coincidence sounds awfully like Frankie Valli’s ‘Grease’ (though it arrived six years earlier). It’s wild and unfettered, and pot (as McCartney liked to call it) may have played an instrumental part in its composition.

Opener ‘Too Many People’ could have been the first Bond theme tune to slip into cod-reggae, if it wasn’t for arbitrary, throwaway lines like “too many people… losing weight!” On near-title track ‘Ram On’, the DIY nature of the record is best exemplified, as Macca pares everything down to a simple ukulele with whistling and mouth trumpets drenched in echo to give it a commodious and welcoming feel, while ‘Dear Boy’ and the lush ‘The Back Seat Of My Car’ demonstrate the singer’s unerring ability with peripatetic melody; here he proves once again that nobody can write a pretty ballad like Paul McCartney in full flight.

Least successful are the various rock ‘n’ roll jams like ‘3 Legs’ and ‘Heart of the Country’ (the latter of which was the sort of thing that kept Status Quo in bread and butter and Bolivian marching powder for decades). In fact, ‘Why Don’t We Do It In The Road’ from the White Album aside, Lennon was always better at the straight-ahead blues rock number, whereas Macca’s other key influence, dance hall from the 1920s and 30s, was always his strongest suit; and so it proves here. And then there’s ‘Uncle Albert / Admiral Halsey’, probably the best known track here; it more than any song signified the way his post-Beatles career would go, with flashes of genius and moments where you sit there and wonder what the bloody hell he’s going on about.

Ram is often described as patchy, but that feels like a harsh summation. It’s a record by a man and woman unburdened, enjoying the happiest days of their lives. It’s full of hope and honesty and goofing around. Unlike so much music from the era, it wasn’t trying to shift units or promote itself as ‘real’ music. In fact Paul McCartney probably doesn’t give a toss if you like it or not.