The prevailing doxa vis-a-vis Orange Juice is that they mediated a certain form of insular dissatisfaction with the dour personal/political hypochondria of their post-punk forerunners and peers. Indeed, they are intermittently feted as having presciently tapped into a stream of hitherto unexplored and, at the time, resolutely unfashionable longing for a smidgen of a pre year-zero remystyification of the pop formulae. A beguiling legacy perhaps for a suburban group of Velvet Underground acolytes, but one which served as a subsequent litmus test of the twin aesthetic and ideological victories and failures of both the mutated punk and new pop. Edwyn Collins’ early propensity for employing reassuringly subversive anti-machismo amid the deceptive conventionality of actual love songs imbued Orange Juice with an entirely syncretic musical language, eventually redolent of the most gloriously stilted of white boy punk-funk. Tenderness, innocence and feyness abounded.

And it would become intertwined with what was a perennially androgynised mode of narrative expression, annexing traditional conservative notions of the glamorous erotic pursuit and recasting the role of the assertive and intimidating female attempting to ensnare the serially uninterested and nervously bookish male. A version of sexual politics prevalent amongst contemporaneous groups of the Young Sound of Scotland, yet rarely echoed with quite as much foppish relish. Sonically though, Orange Juice maintained a similarly re-interpretative approach, forging a rhythmic endpoint devoid of the unseemly brashness of punk buzz and cross pollinated with the curt incisiveness of Nile Rodgers.

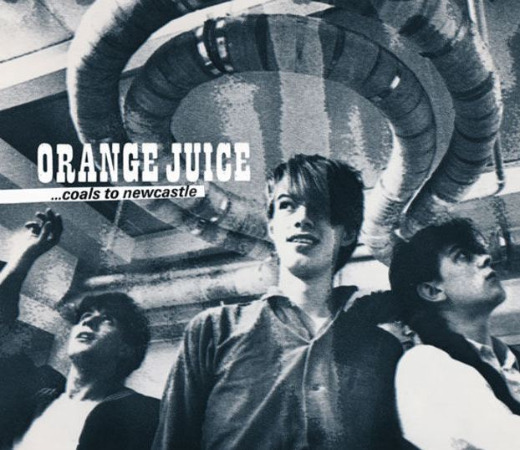

Coals To Newcastle, Domino’s questionably exhaustive CD/DVD box-set, charts the groups eventual synthesis of this agitated garage primitivism with the palpably day-glo byword for what would become the hallmarks of the new pop. Yet there was a relative rawness there too, early on. In particular, an unreleased first LP and previously available singles collection impressively manages to provide evidence of an embryonic psycho-navigation of the deteritorrialized no man’s land between the early VU and a brand of socially inhibited aggro funk. Although more obviously located in the 303/sax re-enforcements of their Rip It Up era ascendency, the trembly Roger Mcguinn worshipping ‘Consolation Prize’ remains the most oddly inspiring of all Orange Juice’s initial gropes for greatness. Collins is, of course, "too delicate" yet triumphantly reassures himself with a series of gradually more celebratory declamations of unsuitably for the expected gender role society has bequeathed him: "I’ll never be man enough for you!".

Such a charming expressions of frailty are frequently unearthed on debut LP You Cant Hide Your Love Forever, and would most likely be misread as irony in our current comments box culture, with earnestness often utilized as a façade to blurt out Vice exalted moral relativism. But an organic melding of precognitive disco funk and conspicuous shards of Gretsch chime imbue the likes of ‘Falling and Laughing’ with enough paired down tension to render such earnestness sonically measured.

In some quarters their most celebrated effort, Rip It Up arrived replete with invasively obvious brass stabs and lyrical simplifications that served to tease out the forthcoming alleviation of textural tension and onset of thematic polarity that was to come. Yet there are tantalising wee possibilities of alternative sonic futures, from the Tony Allen inspired rhythmic complexity of newly acquired drummer Zeke Manyika through to Collins wholesale embracing of a libidinous primacy that cross pollinated a polyrhythmic headcharge and his well developed sense of literary irony to ravishing effect.

Such musical equdistance was never quite fully recaptured by the group as they slog on through the doleful predictability of Texas Fever, yet somehow arrive at the criminally underrated The Orange Juice, a record so seemingly comfortable with its own trajectory of longed for mannerism and outrageously exoticised grandeur that the fizzled out guitar contortions and end of the bottle soul croon of Collins detached laments retain an arresting effectiveness. Its the sheer emptiness of the romantic possibilities on offer here that most jar with the sugar rush fringe flappery of Orange Juice V.1, yet the unflinching bitterness unfolding during the likes of ‘Out For The Count’ gesture at a band as occasionally reliant on emotional dissection as rhythmic dissemination.

Exuberant and often celebratory though they could be, there was also a definite sense that their tweeness was vindicated by a canny incorporation of a form of frippery, which preternaturally injected their music with a sense of progressiveness when pitched against the achingly adult and often unremittingly bleak landscape of the post-punk aesthetic. Yet this new monolithic collection of material serves in part to bolster a nagging feeling that Orange Juice will remain a heartening yet ultimately throwaway excursion into the middle class inanity of an ethos that became a codified genre.