And so Kevin, Nina and Alabee walked hand-in-hand, back to the land where purple rain washes over strawberry fields, and there they lived happily for the rest of their days. The End.

Or so you’d think. But real life doesn’t work like that. It seems the black dog isn’t so easy to shake off with just a few sunrays and some funky wah. No, Kevin Barnes isn’t happy again, and he’s going to tell us all about it.

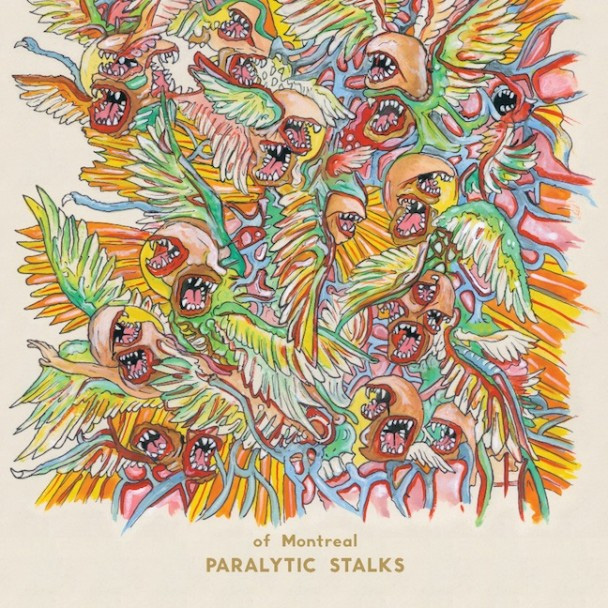

Of Montreal fans will be used to the format by now: nude compositions of Barnes’ innermost thoughts, his ups and downs tracked through pangs of sour apple MIDI-funk, kaleidoscopic harmonies and candy-maze song structures. Much of the appeal behind 2007’s excellent Hissing Fauna, Are You The Destroyer? came from the way Kevin’s lyrics transcended the typical dear-diary confessional, exposing a unique view of the human condition at its most fraught. The disorienting effect of mental collapse, coupled with the fits and swings of familial breakdown, seemed to propel Kevin’s psyche into other astral plains ,complete with their own Freud-like vernaculars of ‘mood shifts’ and ‘destroyer spheres’. Paralytic Stalks eschews such constructs, killing off the Ziggy-like alter-egos (such as Georgie Fruit) which once allowed him to step out of character and observe his neuroses in a more objective way. Instead we’re left with an unabashed account of Kevin’s issues laid out as explicitly and as clangorously as possible.

“I spend my waking hours / Haunting my own life” begins the deliberately-clunky chorus on ‘Spiteful Interventions’. Emo kids on tartrazine have come up with better musings on depression – Kevin did so himself in the opening verse to ‘Gronlandic Edit’ from Hissing Fauna… We’ve been here before, but granted these lines bear a ring of truth in that Kevin’s work has become as much a vital form of auto-therapy as it is artistic expression. Gone are the liminal non-sequitors, the cryptic personal references and amnesiac wormholes that drew us into his world. “I made the one I love start crying tonight / And it felt good”, continues the chorus. By jettisoning the more colourful aspects of his songwriting, we’re left with little but passive-aggressive gripes – a laundry list of woes internalising his every conflict. The listener is transported to the couch-side, made to play the role of therapist who must endure a one-sided counselling session of unsympathetic grievances. By the time Kevin gets round to pinning his personal issues on his parents on ‘Ye, Renew the Plaintiff’ we’re no longer therapists but nervous guests trying to make it through an embarrassing dinner party.

Paralytic Stalks endears itself better when heard through stereo speakers as opposed to headphones. Not only does it create a welcome distance between the lugholes and Kevin’s megaphonic plaints, but it also allows the busy arrangements to unfurl in a more digestible way. Of Montreal fans will have come to expect a few idiosyncratic mood switches and extravagant flourishes, but this album is choked on ideas. Kevin seems happiest when trying to cram as many sounds into the mix as possible, but trying to gain a handle on the dozens of instruments whirling around can be exhausting to say the least. Prolonged listening sessions failed to imprint any particular hook into my brain; instead I found myself walking around with my internal monologue narrated in Barnesian cadence, rambling and changing as is his wont. Perhaps this is the desired effect of Kevin’s freeform approach to songwriting – that is, to mimic the complex neural pathways of human thought by showing them through a broken mirror. This was certainly true of previous outings. However, all too often Paralytic Stalks feels like an attempt to assume the role of indie-pop’s Steve Vai by competitively crushing structural formats underfoot until there’s nothing left but dusty granules.

The album is at its best during the few brief spells where the mix is allowed to breathe, namely on the three-song run from ‘Dour Percentage’ through ‘Malefic Dowery’. The latter traces a line back through psychedelia’s obsession with vaudeville, juxtaposing Dickensian imagery of “debtor’s prisons” with pastoral flute and acoustic picking. Moments like this are few and far between however, with one too many tracks falling under the ‘difficult listening’ banner to keep the record from falling apart.

Paralytic Stalks raises questions as to whether the artist’s primary role is to please one’s audience or oneself. And how should the listener react if the odds are skewed heavily towards the latter? It’s understandable that this is fiercely personal music, essential to the composer’s own mental welfare if nothing else and therefore must be produced for the sake of his own sanity. No doubt Kevin Barnes is aware of this when he sings “Lately all I can produce is psychotic vitriol that really should fill me with guilt / But all I have is asthmatic energy”. I couldn’t have put it better myself, and neither could I agree more with the last part of the same chorus: “There must be a more elegant solution”. There must indeed.