So yeah, this is a review of an reissue that came out a couple of months back – being timed to coincide with the twentieth anniversary of its original release – and to that end is a shade tardy. It was a victim of the autumn postal strike, you’ll be fascinated to know; the copy originally posted to this writer is presumably balancing a wobbly table in a sorting office somewhere. Still: this does all mean that we can reflect on how the Man Behind The Music™, Kurt Cobain, manages to maintain a posthumous presence in global media at the close of the 2000s, thanks to, oh, <a

href="http://edition.cnn.com/2009/SHOWBIZ/Music/12/14/courtney.love.custody/index.html" target="out">stories like this and other fairly depressing episodes. Were Perez Hilton or Sun gossip bellend Gordon Smart to glance through the volume of photos included as a booklet with this repackage – dating from 1987-90, I guess, and mainly black and white – I’m sure they would agree that that scruffy dead guy really pulled himself up by his bootstraps and transcended his shouty origins to cement his status in the world of celebrity. Especially in the last fifteen years.

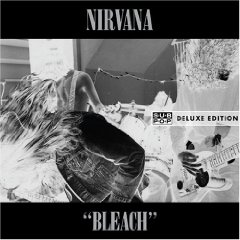

Nirvana are a band whose music – likewise their image – is exposed and out there in the widest of wider worlds, as is right and proper. Therefore, even if this review was being written by someone whose opinions anyone cared about, it would still be a mere pebble flung at the riot-cop charge of the mainstream view – that Bleach is a tentative toddler step towards the conquering pop nous that would secure the trio global figurehead status. This is not untrue, but it’s unnecessarily limited. It is correctly brief (not far over half an hour in its original, eleven-song incarnation) and creates unlikely earworms from bare-brick song structure and dually savant/Cro-Magnon riffs. While Cobain and Krist Novoselic eventually grew frustrated of Chad Channing’s rudimentary drum skills, and replaced him with Dave Grohl, his tubthumping does pretty much all it needs to here. I don’t profess to know how much it costs to remaster an album, or to what extent this is a ‘how long is a piece of string’ question, but I’m guessing the paint job on this reissue cost more than the oft-quoted $600 that Seattle producer Jack Endino charged Nirvana for his services in 1989. (Is this the most famously lowball album budget in rock history? It could be. Although if you know different you might be a sad bastard.)

Endino’s ability to realise that tinkering ought to be kept to a minimum when handed a gravelly, grimy rumble like Bleach is a big factor in the album’s success as a statement of where Nirvana were ‘at’. It’s as decisive a sound as Butch Vig brought to Nevermind, or Steve Albini (before Geffen’s wrongheaded insistence on a polish, anyhow) to In Utero. At the risk of wading into the rawk’n’rawl mythology pool for a neatly rounded observation which glosses over the fact that, you know, a guy shot himself in the head because he hated his life so much, it is pretty picture-perfect how Nirvana lasted long enough to make three studio albums which each have distinct and iconoclastic production values, and yet all inform each other in a weird way. (In Utero is easily as rackety and unfettered as Bleach overall, but also contains a greater proportion of the radio-informed pop moments that Kurt would have liked to have sneaked onto the debut, were this not the done thing in the nascent Washington grunge scene of the time.)

Conversely, Nirvana – certainly the Nirvana of this time – were an awkward and puzzling and… weird proposition. Little surprise, in hindsight, that of the assembled Sub Pop likely lads, it was Mudhoney rather than they who were most tipsters’ bet for likely success. Nirvana is a terrible name for a nominal punk band, firstly: Kurt couldn’t be expected to have known about the late-60s psych band of that name (who did very nicely out of the inevitable 1992 lawsuit, apparently), but it suited them. It never suited Kurt and co’s Nirvana, except when printed on shitty tie-dye bootleg shirts you still see at provincial Sunday markets. Secondly, what sort of band releases a cover version as their debut single and expects to be taken remotely seriously? ‘Love Buzz’, a song by, er, late-60s psych band (from Holland) Shocking Blue (who presumably still do very nicely out of the royalties) must surely have caused a few headwounds from all the scratching, but Nirvana conquer the composition without having to leave the garage it was birthed in; unsurprisingly, their version is rather better known now.

"Can you feel my love buzz?", high as its authors no doubt were on the sheer elation of being part of a global movement towards a singular consciousness and some other shit like that, operates at about the same depth as most of Cobain’s lyrics here. Written, he later confessed, more out of necessity than a desire for expression, Bleach‘s lines run the gamut from schlocky punker trash-culturisms (‘Floyd The Barber’, which riffs on American sitcom The Andy Griffith Show), repeat-to-fade non-slogans essentially meaningless to the average listener (‘School’, ‘Negative Creep’) and what is hard to avoid describing as ‘goth poetry’ when observing it written down (‘Paper Cuts’). As such, it only bears further analysis insofar as to marvel at the 180 turn Cobain pulled on this issue, coming to spew out lyrics weighed down and crawling with allegory and metaphor.

At this point, a certain briskness seems to become the trio: songs like ‘Negative Creep’, ‘Swap Meet’ and ‘Mr Moustache’ rattle along faster than anything their Sub Pop peers were kicking out. ‘Sifting’, the album’s original closing track (‘Big Cheese’ and ‘Downer’ were added to the CD version), seems to be Kurt’s most flagrant salute to the slothsomely slow stylings of The Melvins, the band for whom he did some roadie stints. There was perhaps too much punk in their blood for them to bring it off, though, as it doesn’t really convince like most of what comes before it.

Presumably in the name of ‘value’, you get an eleven-track live recording of a Nirvana show, recorded in Portland in February ’90, tacked onto the end. The setlist is a mixture of Bleach jams and assorted non-album Nirvana tracks of the time, including the Vaselines cover ‘Molly’s Lips’ and ‘Sappy’, which wasn’t released until three years later. There aren’t any Nevermind songs in the set, although they were playing ‘Polly’ and ‘Breed’ around this time (see 1995’s From The Muddy Banks Of The Wishkah for them, mind). Listening to a recording of a band knocking their gear about and making random feedback at the conclusion of their final song is not an edifying aural spectacle that will in itself change any fifteen-year-old’s life, but it does form part of a bigger jigsaw that lets you in on why people started to give a shit, back when.

Why exactly people give a shit now is a question whose answer is tangled like a world of phone cords, but if, in some nebulous way, stories on CNN about Courtney Love’s parenting ability trickles down into continued appreciation for a rad two-decades-old punk rock record, then… that is a light in the darkness.