On the release of Bryter Layter in 1970, the agoraphobic Nick Drake put the nails in the album’s coffin by failing to accompany it with any publicity – or indeed barely any live performance. It was only after his death, (four years later from an overdose of prescription drugs), that the self-destructive singer’s music garnered any real praise.

It’s telling that in his life he never really fitted in, and whether it was a cause or a symptom, his music followed a similar fate. He was a man out of sync, out of time. By the turn of the decade, when Bryter Layter came out, free love had been usurped by the encroaching paranoia of amphetamines, Hells Angels and an altogether heavier noise. Grizzled leviathans like Led Zeppelin, Black Sabbath and Deep Purple were tearing up the popular music map.

Even John Lennon – the last of the big hitters to grow disenchanted with Peace ‘n’ Love’s glib appeal – had left the party for the primal scream therapy that would fuel the high watermark of his solo career, the Plastic Ono Band. All the while, Drake earnestly persevered with his self-fulfilling whimsy, blinkered and inward looking.

As an artist, he was unlucky in his timing. It was an era of precocious talents, and cruelly, he would narrowly miss out on the Haight-Ashbury heyday that would have suited him so much better.

Inevitable comparisons with Dylan may be a little unfair on the Englishman, but in his way, the American too was a relic. He admitted as much in the first part of his Chronicles autobiography, declaring he felt he belonged in an earlier age. But where he canonised his nostalgia to forge a future, Drake merely sounded overwrought, swamped in melancholia.

So if he was to be judged on his contemporaries of the period, then the reissue of Bryter Layter in this instance has a cast iron alibi. For in the cold light of 2013, it seems unfair that on release it sold barely a handful of copies.

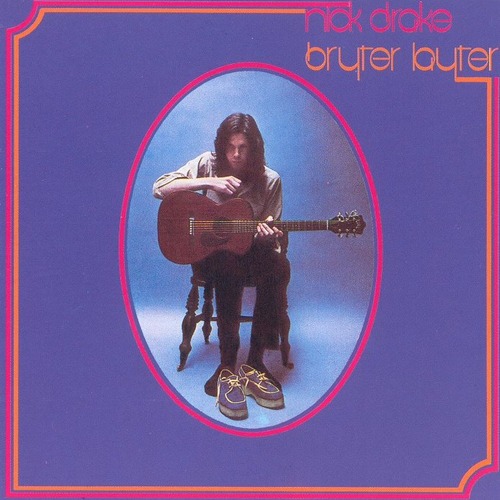

The reissue has added appeal too. It’s a lovingly crafted demonstration of the ethereal qualities a physical release has over its successors. Here, a Russian-doll of boxes indulge the record inside, reproduced with its own ageing process – even complete with the original price tag, all making a noisy argument for vinyl as the superior format. Before the record’s even out of the box, it’s an occasion. There is simply more space for expression. There’s a gig poster of the period, a reel-to-reel tape prints, and hand-written lyric sheets complete the illusion. Cracking the case, it smells better than the inner spine of a new paperback, holier than a pair of box-fresh trainers.

And while the window-dressing doesn’t actually change the sound, it surely adds to the experience. It’s not just a smokescreen, and the knowing nod to nostalgia in this case is relevant to Drake, a man himself in awe of the past.

But for an artist so famously maudlin, it’s a surprisingly breezy record. ‘Introduction”s wordless, soaring strings segue into ‘Hazey Jane II’, which – albeit with horns that sail dangerously close to muzak, is saved by its lilting steel guitar, assertive backbeat and the singer’s dulcet delivery.

‘At The Chime Of A City Clock”s brooding backdrop is the perfect foil for Drake’s breathy delivery, even if his underlying self-doubt is betrayed by the syrupy strings which almost completely drown his lead.

Bryter Layter‘s shortcoming is that for large parts it merely sounds like a hangover from 1967. The title track is all whimsical flutes and a firing squad of flower-barrelled rifles.

The malaise is lifted by the stoic blues of ‘Poor Boy’, shaking off any self-pity with a deep gospel undertow. But frustratingly again it falls victim to unnecessary instrumentation – this time a meandering saxophone. And ‘Fly’ could have come from cutting-room floor at The White Album sessions two years previous, complete with ‘Blackbird’ finger-picking and a jovial harpsichord cribbed from ‘Piggies’.

In his lifetime Drake was rarely cited as an influence, which rather plays up to his myth of doomed inertia. Yet final track ‘Sunday’ bears more than a passing melodic resemblance to Bowie’s ‘Kooks’ from Hunky Dory, released a year later. More recent cap-nods are starker. Here, Belle & Sebastian’s Stuart Murdoch is the most obvious debtor.

Ultimately however, Bryter Layter‘s jaunty hippy vibe is at odds with Drake’s insecurities. On ‘One Of Those Things First’ he sings, "I could have been a sailor, I could have been a cook", before asking "Would you love me for my money; would you love me ’til I’m dead?" on ‘Northern Sky’. All of which goes some way to explaining the difficult marriage at the core of his work, and why it never sat – like its author, with any real self-assurance, a fragility that was unable to keep pace with an inevitably growing cynicism in society, and in music.