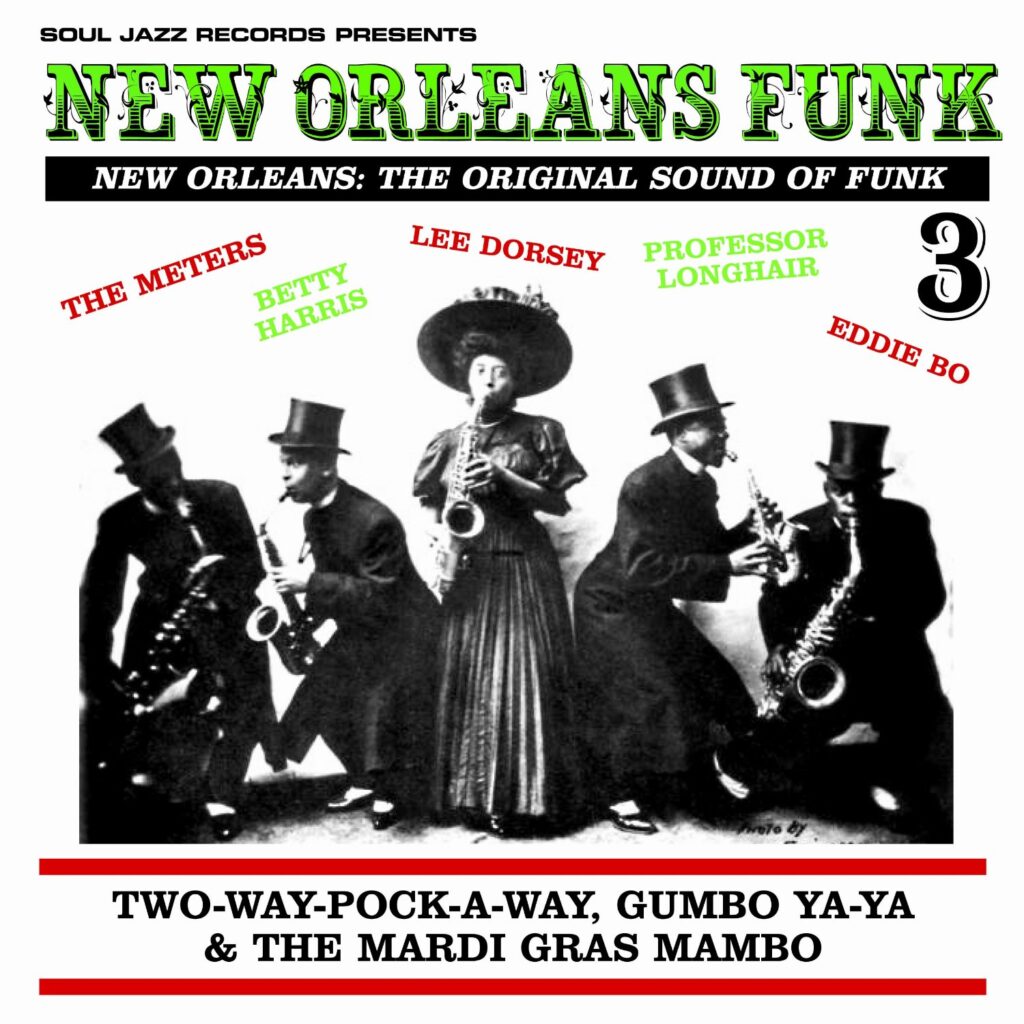

In 2000, on the odd occasion there were people back at my house, drinking cocktails after the pub kicked out, then they would be guaranteed to get up and start dancing within minutes of me putting the original Soul Jazz New Orleans Funk compilation on. And I dare say if I was still holding impromptu, boozy, late night house parties then this excellent third volume in this series would have exactly the same effect. (I’ve started a monthly social recently in a pub in Kings Cross and as well as Afrobeat, Krautrock and Cosmic Disco, New Orleans funk makes the backbone of the night and you can see the Pavlovian reaction people have to Roger And The Gypsies, Lee Dorsey, Betty Harris, Ernie K. Doe, the mighty Meters, Irma Thomas, the Wild Magnolias and Eldridge Holmes; they can barely resist the urge to get up and dance when this jamming backbeat funk is on. And sometimes they don’t.)

Of course things are different in the world of New Orleans music now. Because of the immediate impact and after effects of Katrina in 2005, compilations like this can’t help but be seen through a prism of natural disaster, social inequality and human inaction. Most of NO’s innovations in music from jazz to bounce via notable contributions to the genesis of rock & roll and funk, have occurred at times of great financial hardship. So while I don’t think there’s anything wrong per se with people on the other side of the globe revisiting black American culture from previous generations it’s simply bad form to expect to enjoy this music without at least knowing something of where it comes from.

The reason I included the introduction above, in case it’s not immediately clear, is to point out that I’d be a massive hypocrite if I pretended I had a problem with the fetishisation of black music from previous generations: I clearly do it myself. But at the same time I should say that I have a deep suspicion that there’s something unwholesome about people who fetishise black music from the 50s, 60s and 70s while switching noticeably to all white contemporary sounds. Like black music’s just super when it’s been through a two or three decade quarantine period like it’s fine wine not living, breathing, evolving culture.

In short: it’s never just about the music, man.

You might think it’s wrong headed to look at this kind of comp (culled from the 1960s and 1970s) via knowledge of a disaster that happened years after it was all recorded but it’s only natural (Katrina exists on a continuum of mistreatment/misfortune that the poorest residents of NO have always suffered) and bears up to close examination.

The makers of the HBO show Treme realised that if you want to tell the story of this city in miniature, then you concentrate on the tales of those involved two of its biggest, most important, most successful working class industries: catering and music. I really like the show and eagerly await a fourth series but I guess I feel that music travels better than food and – despite psychologist Stephen Pinker calling music little more than evolutionary cheesecake and food self-evidently being an essential human requirement – it’s the stories of the musicians not the chefs that really fascinates me.

The story of New Orleans music raises many questions: what was it about this city that led to the birth of jazz? Why is it so easy to spot New Orleans funk from the drumming alone? What are the through lines (if any) between all of this city’s music, even taking in the sludge metal of Goatwhore and the bounce tracks of Lil Wayne? And more to the point, how does its newly reinvigorated spread across the globe help bring pride and finance back to the mainly black communities messed up after the storm?

The second track on this great comp is Professor Longhair’s ‘Go To The Mardi Gras’ and was a recurring theme (song) in the show Treme. It was the track that John Goodman’s character Creighton Bernette – a white, middle class English professor at Tulane University, procrastinating over his much talked about book on the great flood of 1927 – played on the family’s stereo before they headed out to join the annual holiday celebrations. When the likeable Bernette (something of a metaphor for civic pride) – based on real life academic and blogger Ashley Morris – commits suicide, the song is heard again and again in different contexts. One is initially of loss and grief, then later becoming a focal point of hope, before finally regaining its status as a communal party anthem nonpareil.

In times of trouble people turn to ‘traditional’ roots culture for support and comfort as well as for more political reasons and this is as true of the New Orleans of the last eight years as it is of Cairo today or London during the Second World War. When these compilations first appeared, we were at the tail end of the late 1990s funk revival – so there was plenty of interest in acts such as the Meters or Eddie Bo. However other aspects of this music were perhaps less popular than they had ever been. Some of it appeared downright alien such as the tradition of the Mardi Gras Indians or simply old fashioned and anachronistic such as the style of the marching brass band. Initially after Katrina it looked like both things were sure to die but finally the fortunes of these styles have finally turned a corner. One can even hope that in the long term, they have been saved.

No one is saying that 2013 is a particularly kind environment for New Orleans brass bands to operate in but they have become symbolic of the slow and often painful process of regeneration in the city. The Dirty Dozen Brass Band are the ‘newest’ act on this album having only formed in 1977 (they’re still gigging strong in NO today). The second line syncopation and marching band style is fantastic for their reworking of the stone to the bone jam ‘Do It Fluid’ (originally by The Blackbyrds). More recently their response to Katrina was to cover Marvin Gaye’s What’s Going On in full in 2007. And this hopeful reversal of fortunes isn’t tokenistic, the aptly named Rebirth Brass Band (once featuring legendary trumpeter and Treme star Kermit Ruffins) have weathered the storm and come out even stronger, winning, as they did, a Grammy in 2011 for their album The Rebirth Of New Orleans.

While younger Nawlins artists need cash, recognition and respect, compilations like this still matter as well, helping spread the cultural message about the city, attracting the tourists that it so desperately needs.

Even though a lot of time has passed since most of these tracks were cut, this isn’t to say that all of the artists here have retired or gone to join the great brass band in the sky. I’m sure Willie West, who opens proceedings with a sweet slice of acoustic guitar led soul (backed by The Meters and produced by Allen Toussaint – New Orleans funk dream team) will be pleased to crop up here given that he’s still gigging strong today… albeit based out of Minneapolis post Katrina. The Meters also crop up backing Eldridge Holmes (‘The Book’) and Lee Dorsey (‘What You Want’) on separate tracks, again produced by NO mainstay Toussaint. I love Lee Dorsey’s voice. He’s one of those guys who should have been much bigger than he was and every time I hear him it’s like a shot in the arm. A former soldier, boxer and car mechanic he had mixed feelings about his recording career. (One story I heard even had Allen Toussaint making Dorsey leave his garage to come and take part in a recording session at gun point – if anyone can substantiate this, I’d love to get an email about it.)

After Dorsey, probably the true star of all these comps is Betty Harris who wasn’t even from New Orleans. She was born in Florida and returned there a decade ago but did most of her outstanding work in the Crescent City. That she was the daughter of two gospel preachers makes total sense when you hear her let loose – which she does twice on this compilation (‘Trouble With My Lover’ and ‘What’d I Do Wrong’). Elsewhere, The Dixie Cups (perhaps most famous for their cover of James ‘Sugar Boy’ Crawford’s ‘Jock-A-Mo’ reworked as ‘Iko Iko’) are featured with ‘Two Way Pocky Way’. Both of these songs are atypical of their standard pop sound and are examples of their girl group take on the sound of the Mardi Gras Indians. Both songs are essentially about the ritualised and codified behaviour that happened between rival groups of Indians if they met accidentally in the street (these rituals apparently replacing straight up fist fights). ‘Iko Iko’ details the chance meeting of one tribe’s ‘Spy Boy’ with another’s ‘Flag Boy’ while ‘Two Way Pocky Way’ is a shouted order for a member of an opposing tribe to get out of the way.

The hallmark of a great Soul Jazz compilation is the balance between the stone cold classic and the well selected deep cut, and this compilation serves up both well. The Explosions, The Deacons, Diamond Joe and The Rubiyats make up the number of rarities. It’s really worth buying, whether you’ve got a house party imminent or not. And whether you decide to spend the rest of your hard earned cash on something newer by Lil Wayne or Goatwhore is completely between you and your conscience.