Paranoia is one of the essential facets of the post-punk mindset. From Throbbing Gristle’s evocations of urban claustrophobia to Gang of Four’s scrupulous dissections of social facades and This Heat’s in-the-shadow-of-the-bomb tribalism, all are given impetus; given that nervous twitch that characterises their music, by the suspicion that things are not as they seem; that undercurrents that run through society – political, social, manifested in every part of the body politic from economics to basic politeness – are working to undermine our human ability to love, think and feel freely. When applied to the Italian post-punk groups that sprang up in the aftermath of Italy’s ‘Years of Lead’ however, that paranoia takes on a whole other level of intensity.

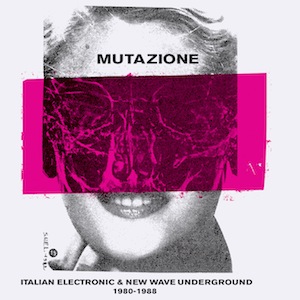

Just a quick Google search on the years of leftist/rightist terrorism that affected every facet of Italian society from 1969 onwards and which left a shocking amount of people dead and injured, turned up some of the following names – Avanguardia Nazionale, Vincenzo Vinciguerra, L’Ordine Nuovo, Propaganda Due, Brigade Rosse: right wing extremist cells, covert masonic lodges with links to the assassinations of journalists and bankers, leftist kidnappers and murderers. The Italian bands that appeared around this time weren’t dealing with a vague sense of dissatisfaction bought on by studying too many CND leaflets and reading William Burroughs, but with the cold hard fact that their lives were being coerced and controlled (and occasionally ended) by shadowy agencies existing under their level of awareness. Unsurprisingly, the music that came out of this movement, on the evidence of this magnificent compilation by Strut, carries that twitching paranoiac pulse through every fibre of its being. Similarly unsurprisingly the vast majority of it is sick as fuck.

Check out the electronic pulse that courses through 0010110000010011 (that’s binary for ‘Cancer’)’s ‘Naonian Style’ and gives what would otherwise be a fairly straightforward piece of avant-pop a hand-grenade-between-the-teeth intensity, or the sandpapered and analogue-warped female vocals on Plath’s ‘I Am Strange Now’. These don’t feel like attempts to fit into a recognisable seam of avant-garde expressionism, but rather earnest attempts to sculpt into sound a suffocating sense of claustrophobia and tension and to hammer the body into a total autonomous zone, completely free from outside interference. The best tracks on Mutazione feel like the work of kids attempting to seize back their destinies with any instruments that lay in their path.

Of course, as with all musical movements, however loose, these collected tracks do not constitute a year zero and the best moments look both forward and backwards in an attempt to capture the spirit of their times. Some of the fizzing analogue synthesis of italo disco and house is evident in pieces by Victrola and Neon, while the Italian love of the wilder edges of progressive rock is evident in several tracks, most notably those by La 1919 and A.T.R.O.X., while Tasalay’s ‘Crisalide’ is a malevolent, tribal howl that would be unthinkable without Goblin’s terrifying Suspiria soundtrack.

It’s these more extreme moments that really serve to elevate the compilation and give it its identity, particularly where the artists involved demonstrate a willingness to delve into the deeper ends of the then-burgeoning industrial and power electronics scenes. Most notable of these is Laxative Souls’ ‘Nicolai’, a crude recording of a phone call – made by a member of leftist terrorist organisation Brigade Rosse explaining where the body of murdered MP Aldo Moro could be found – bedded into a wheezing electronic backdrop. It’s utterly hardcore; a completely unafraid piece of art with deadly serious intent. Spirocheta Pergoli’s ‘Romero’s Living Dead’ is more playful, perhaps, but no less unnerving. A combination of lurching bontempi rhythm, slashing guitar and nerve rattling female screams that sounds quite unlike anything else I have ever heard. That the album ends with ‘Auschwitz’ by power electronics pioneer Maurizio Bianchi is appropriate, being as the album it hails from, Symphony For A Genocide, is probably one of the most powerfully political pieces of music of the 20th century: a comic/tragic scream of freedom in the face of oppression, and a melancholy reflection of man’s stupidity and weakness.

If you read an interview with any members of the class of ’68 or ’76 these days it has become a cliché to see them moan about the lack of political engagement in music. Where are the kids with three chords and the truth? The oddly barnetted troubadours facing down the people in power? What this thoroughly dim viewpoint fails to take into account is that any attempt to criticise and engage with society’s evils through conventional ‘musicality’ has long ago been recuperated and castrated by commercialisation and familiarity; with the deadening realisation that we’ve seen it all before and it achieved fuck all anyway. What this superb compilation demonstrates is the huge variety of ways in which musicians can carve new freedoms for themselves in the face of oppression and, in doing so, leave a path for artists of future generations.